Every year during Black History Month, many well-meaning people post information that they know little about. Recently I saw a post about the “Great Mail Kingdom” that glorified one if its leaders, Mansa Musa (King of Mali from 1307 to 1332), since he was considered to be one of the wealthiest men in history. Such Black History posts, however, are very disturbing because they show a lack of critical understanding of that history. I commented that I am providing an alternative reading of Mansa Musa which I think is equally significant. We have to re-read African history from a more informed point of view instead of just repeating what was taught to us. Most of what we know comes from western scholarship which prejudiced “state societies” and so-called “great warriors and Kings” because that reflected their own political concepts. So “great kingdoms” were studied at the expense of other peoples and from the point of view of the people. We should not uncritically accept such perspectives.

I think promoting the slave traders of the great African Kingdoms, including Mansa Musa, IS misguided. That is not what we should be teaching our children, that because you become extremely wealthy by exploiting and enslaving people, that this makes you “great” in history. We should be explaining that ALL such systems of exploitation are WRONG, not glorifying them.

Previously, WE (African Americans) studied Africa generally because we did not know specifically where in Africa we came from, who our people are/were, and accordingly, where we fit into African history. Moreover, the history of Africa is written from the perspective of the "Great African Civilizations" and more specifically, from the viewpoint, events, and concerns of the "ruling class" and not from the viewpoint of the people and those who were oppressed by them. Because of genetic testing, we can study African History specifically to find out where one comes from and their place in history . We can reread African History so that the voice and narrative of the people is told and not just that of the rulers.

IBN BATTUTA DESCRIBES MALI IN 1352

When Ibn Battuta first visited Cairo in 1326, he undoubtedly heard about the visit of Mansa Musa (King of Mali from 1307 to 1332). Mansa Musa had passed through the city two years earlier making his pilgrimage to Mecca with thousands of slaves and soldiers, wives and officials. One hundred camels each carried one hundred pounds of gold. Mansa Musa performed many acts of charity and "flooded Cairo with his kindness." So much gold spent in the markets of Cairo actually upset the gold market well into the next century. Mali's gold was important all over the world. In the later Medieval period, West Africa may have been producing almost two-thirds of the world's supply of gold! Mali also supplied other trade items - ivory, ostrich feathers, kola nuts, hides, and slaves. No wonder there was talk about the Kingdom of Mali and its riches! And no wonder Ibn Battuta, still restless after his trip to Al-Andalus, set his mind on visiting the sub-Saharan kingdom. Here is an excerpt from his travel journal:

“Sometimes the sultan [of Mali] holds meetings in the place where he has his audiences. . . . Most often he is dressed in a red velvet tunic, made of either European cloth called mothanfas or deep pile cloth. . . . Among the good qualities of this people, we must cite the following:

The small number of acts of injustice that take place there, for of all people, the Negroes abhor it [injustice] the most.

The general and complete security that is enjoyed in the country. The traveler, just as the sedentary man, has nothing to fear of brigands, thieves, or plunderers.

The blacks do not confiscate the goods of white men who die in their country, even when these men possess immense treasures. On the contrary, the blacks deposit the goods with a man respected among the whites, until the individuals to whom the goods rightfully belong present themselves and take possession of them.

The Negroes say their prayers correctly; they say them assiduously in the meetings of the faithful and strike their children if they fail these obligations. On Friday, whoever does not arrive at the mosque early finds no place to pray because the temple becomes so crowded. The blacks have a habit of sending their slaves to the mosque to spread out the mats they use during prayers in the places to which each slave has a right, to wait for their master’s arrival.

The Negroes wear handsome white clothes every Friday. . . .

They are very zealous in their attempt to learn the holy Quran by heart. In the event that their children are negligent in this respect, fetters are place on the children’s feet and are left until the children can recite the Quran from memory. On a holiday I went to see the judge, and seeing his children in chains, I asked him ‘Aren’t you going to let them go?’ He answered, ‘I won’t let them go until they know the Quran by heart.’ Another day I passed a young Negro with a handsome face who was wearing superb and carrying a heavy chain around his feet. I asked the person who was with me, ‘What did that boy do? Did he murder someone?’ The young Negro heard my question and began to laugh. My colleague told me, ‘He has been chained up only to force him to commit the Quran to memory.’

Some of the blameworthy actions of these people are:

The female servants and slaves, as well as little girls, appear before men completely naked. . . .

All the women who come into the sovereign’s house are nude and wear no veils over their faces; the sultan’s daughter also go naked. . . .

The copper mine is situated outside Takedda. Slaves of both sexes dig into the soil and take the ore to the city to smelt it in the houses. As soon as the red copper has been obtained, it is made into bars one and one-half handspans long - some thin, some thick. Four hundred of the thick bars equal a ducat of gold; six or seven hundred of the thin bars are also worth a ducat of gold. These bars serve as a means of exchange in place of coin. With the thin bars, meat and firewood are bought; with the thick bars, male and female slaves, millet, butter, and wheat can be bought.

The copper of Takedda, is exported to the city Couber [Gobir], situated in the land of the pagan Negroes. Copper is also exported to Zaghai [Dyakha-western Masina] and to the land of Bernon [Bornu], which is forty days distant from Takedda and is inhabited by Muslims. Idris, king of the Muslims, never shows himself before the people and never speaks to them unless he is behind a curtain. Beautiful slaves, eunuchs, and cloth dyed with saffron are brought from Bernon [Bornu] to many different countries. . . .”

40 DAYS JOURNEY FROM TAKEDDA (Mali Muslims) to BORNU (pagan Negroes of the south)

Here, then, Ibn Battuta is describing a Muslim Mali society completely abhorrent to our Balanta ancestors living in the region. Such a society violated their Great Belief which centered on equality. Thus, any kind of hierarchy creating masters and slaves, rulers [kings or Mansas] and subjects, was a direct threat to the Balanta way of life. The idea of shackling children to force them into the foreign indoctrination of a false religion of conquest is an offense of the greatest magnitude.

Below is an excerpt from Volumes II and III of Balanta B’urassa, My Sons: Those Who Resist Remain, which serves as an example of a more informed, re-reading of the History of Mali:

Keita Clan

“While the Soninke lived just south of the Sahara Desert, in the Wagadu Confederation, the Malinke occupied mostly the middle and southern parts of the savannah, near the forest belt. There was peaceful coexistence between both the Soninke and the Malinke (Mandinka). Actually, they both belong to the Mande people.

The Keita Clan was one of many groups near the forest belt. They were originally centered in Kangaba, on the Niger River, which was about 250 miles south of Koumbi.

Exiled Egyptians: The Heart of Africa by Moustafa Gadalla, p.173

In 1230, Sundiata was declared the chief of Kangaba. . .

Sundiata Kangaba began to expand his authority by force, in the name of Islam. His forces began the ugly slave raiding and trade, with their Moslem masters. So, Sundiata became the first main sub-Sahara supplier of slaves.

In order for the aggressive Keita gangsters to justify attacking their northern neighbors, they came up with the story that they were threatened by the Soninke. The Almoravid Berbers who couldn’t destroy the Soninke, got Sundiata to attack them.

In 1235, at the battle of Kirina, Sundiata defeated the Soninke army. Five years later, all of Wagadu was incorporated into his domains, destroying a peaceful civilization. Sundiata shifted his place of residence from Jeriba in Kangaba to a new city, Niani, further down the Niger.

The term Mali, meaning where the king lives, came to be applied to the new Mandingo State created by Sundiata’s Keita Clan.”

Mali

Gadalla continues:

“After Sundiata, the rulers of the Islamic empire assumed the title of Mansa, which means emperor or sultan.

Since Sundiata was not in very good health, his immediate successor-son, Uli (c. 1255-1270), began the tradition among the ruling Keita Clan of following the wishes of their Moslem masters, by making a haj, a pilgrimage to the Moslem capital at Mecca, on the Arabian Peninsula. He came back infused with Mecca’s authority to attack his neighbors, in yet more Islamic jihads. Immediately thereafter, the Keita Clan of Kangaba conquered territories, stretching from mid-Senegal to the border of Niger.

The oral history of the Malinke from the 1200s onward stresses the connection of the Malinke to Islam so as to appease their Moslem masters. An outlandish link of Sundiata’s ancestor with Arabia is believed to be an example of this ‘connection.’

The Keita Clan emerged as a dominant power in sub-Sahara Africa, and controlled the trans-Saharan trades from about 1200 to 1500CE. In the days of the Keita Islamic rule, a major trading rout across the Sahara to Tunis and to Cairo, was utilized often, because Moslem rulers needed slaves that the Keita Clan was obliged to provide. The Keita Clan betrayed their own kind, to make riches. Gradually the northeast trade route became the main one.

The new illegitimate dictatorial Islamic rule eliminated the matrilineal succession system. As a consequence, in the thirty years following the death of Sundiata, the Keita Islamic rule had five rulers.

There were three main periods of bloody disorder in the Keita’s rule, created by disputed claims to the throne. The first showed Sundiata succeeded by three sons, Uli, Wali, and Khalifa. The last son, Khalifa, was overthrown in a bloody coup by the adherents of Abu Bakr, considered to be the rightful heir, as the son of one of Sundiata’s daughters. Abu Bakr then took power.

Sakura, a freed slave of the royal family, managed to secure control of the army, and overthrew Abu Bakr’s reign in another bloody coup. Sakura was also overthrown in yet another bloody coup.

The third emperor of the 14th century, a descendant of a brother of Sundiata, was (Kankan) Mousa (Mansa), who went to the Islamic-besieged Cairo and Mecca, in 1324, where he was infused with authority to attack more neighbors and abduct more slaves, in the name of Islamic jihads.

On his return from Mecca, he conquered Gao and took two of its princes as hostages, along with other children of neighboring communities. These children acted as shields, preventing the Gao people from attacking Mousa’s court.

After Mansa Mousa’s death, probably in 1337, a brief struggle for power ensued before Sulayman, Mousa’s brother, came to the throne in 1341. After his death in 1360, various factions of the Keita Clan began to compete with each other for power, and their hold on power disintegrated.

In short, the empire was maintained by the exercise of dominion of a quasi-Islamic ruling class, by force (al-Umari writes of an army of 100,000, with 10,00 cavalry), for their own profit. As far as the Mande/Malinke subjects were concerned, they have never accepted this illegitimate exercise of power, and were never converted to Islam by their Moslem overlords. They maintained their indigenous traditions.”

Neither, my sons, were our Balanta ancestors, accepting of the illegitimate power, nor did they convert to Islam. Here then, is the ACTUAL point of connection between our most ancient Balanta ancestors, the Anu living in Ta-Nihisi (Nubia, Sudan) and the Balanta living today in Guinea Bissau. Walter Hawthorne writes in Strategies of the Decentralized, in the book Fighting The Slave Trade: West African Strategies by Sylviane A. Diouf:

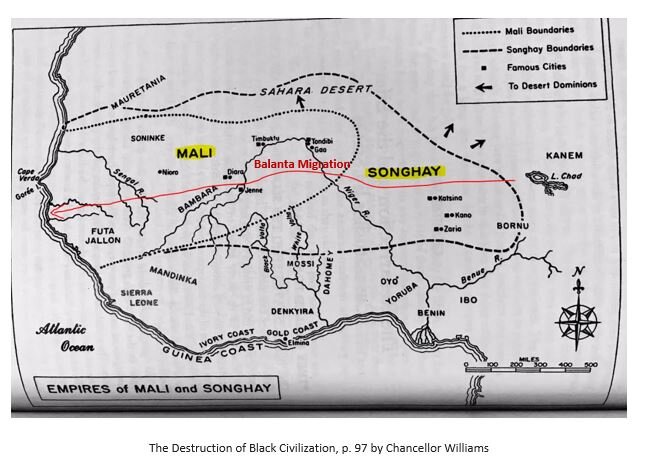

“The Balanta claim that the region between the Rios Mansoa and Geba – an area they call Nhacra, which is part of the broader region of Oio – is their homeland. The Balanta say that they migrated there ‘in times long past’ from somewhere in the east. In addition, Balanta migration myths have two other common threads: the Balanta left the east because of conflicts with either state-based Mandinka or Fula, and these conflicts resulted from a Balanta propensity for stealing from their more prosperous neighbors or desire to avoid enslavement. For example, elder Estanislau Correia Landim told me, ‘The origin of the Balanta was in Mali. For reasons involving Balanta thefts, Malianos revolted against the Balanta. For this reason, Balanta left there. That is, some Balanta were stealing some things. When a thief was discovered, he resolved to kill the person who had discovered him. For this reason, Malianos chased after the Balanta. . . . When the Balanta left Mali, they went to Nhacra and then to Mansoa.”

THIS NARRATIVE THAT BALANTA PEOPLE WERE CATTLE THIEVES, HOWEVER, IS NOT ACCURATE. Balanta people were NOT cattle thieves. Domingos Broksas in the video below explains that in reality, when the Mandinka raided the Balanta villages, the Balanta would flee, leaving their cattle behind. Later, they would go and retrieve their cattle. This is called “Reparations”, not theft.

After Mansa Musa

John Jackson writes,

“Under [Mansa] Musa I, the Mali Empire embraced an area just about equal to that of western Europe. . . . [T]he lifeblood of the empire was trade; and taxes were the paramount source of income for the government. . . . foreign merchants who traded in Mali marveled at the prosperity of the region and noticed that even the common people were not oppressed by poverty. . . .

When Musa I died in 1332, he was succeeded by his son Maghan. Mansa Maghan was neither as wise nor able as his father, and during this reign Mali went into a decline. First, the city of Timbuktu was lost to enemy forces. . . . Secondly, Mansa Maghan was not alert enough to prevent the escape of the two Songhay princes whom his father had been holding as hostages. The escaped princes returned to Gao, where they established a new Songhay dynasty. Maghan died after a four-year reign, and was succeeded by his uncle, Sulayman – a brother of Mans Musa I. Mansa Sulayman was a sovereign of high competence, and he ably presided over the destinies of Mali until his death in 1359.

The great age of Mali was now at an end; for the later rulers were undistinguished men, under whom the empire disintegrated. About the year 1475, the Songhay Empire, with its capital at Gao, rose to supremacy in the west Sudan, as Mali continued to decline. In 1481 Portuguese sailors landed on the Atlantic coast of Mali. The Mali government attempted to hire these Portuguese as mercenaries to fight the rising power of Songhay, but the proposed alliance was never effected. Mali lingered on for nearly two centuries, but its day of greatness had passed into history, and if finally expired from innocuous desuetude. . . .

My sons, in Volume II, I outlined the environment in which our Balanta ancestors existed, from the death of Abu Bakr in 1087 and the fall of the Almoravids in Wagadu (Ghana), to the rise of the Sundiata and the Keita Clan of the Malinke (Mandinka) who, at the battle of Kirina in 1235 defeated his Soninke (Sosso) relatives, for both the Mandinka and Soninke were both Mande people. Sundiata’s victory of the Soninke army, first recorded in oral history by griots, and then written in the Epic of Sundiata, was the beginning of the new Mandinka State called Mali, meaning where the king lives.

The Keita Clan following the wishes of their Moslem masters, infused with Mecca’s authority, began to attack their neighbors, in yet more Islamic jihads following the Almoravids. Because Moslem rulers needed slaves that the Keita Clan was obliged to provide. The Keita Clan betrayed their own kind, to make riches. This continued through Mali’s third Emperor, Mansa Musa, who died around 1337. At the time, the lifeblood of the empire was trade and taxes were the paramount source of income for the government. Our Balanta ancestors refused to pay those taxes. Moreover, Balanta Elder Estanislau Correia Landim stated, ‘The origin of the Balanta was in Mali. For reasons involving Balanta thefts, Malianos revolted against the Balanta. For this reason, Balanta left there. That is, some Balanta were stealing some things. When a thief was discovered, he resolved to kill the person who had discovered him. For this reason, Malianos chased after the Balanta. . . . When the Balanta left Mali, they went to Nhacra and then to Mansoa.

To be sure, Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali by D.T. Niane, Revised Edition states,

“It was from Do, also, that Sundiata ordered all his generals to meet him at Ka-ba on the Niger in the land of the king of Sibi. . . . The arms of Sundiata has subdued all the countries of the savanna. From Ghana in the north to Mali in the south and from Mema in the east to the Fouta in the West, all the lands had recognized Sundiata’s authority.

Sibi Kamandjan had gone ahead of Sundiata to prepare the great assembly which was to gather at Ka-ba, a town situated on the territory belonging to the country of Sibi. . . . Even before Djata’s arrival the delegations from all the conquered peoples had made their way to Ka-ba. Huts were hastily built to house all these people. When all the armies had reunited, camps had to be set up in the big plain lying between the river and the town. On the appointed day the troops were drawn up on the vast square that had been prepared. As at Sibi, each people were gathered round its king’s pennant. [Siphiwe note: As our Balanta ancestors did not have kings, they would not be included in this]. Sundiata had put on robes such as are worn by a great Muslim king. Balla Fasseke, the high master of ceremonies, set the allies around Djata’s great throne. Everything was in position. The sofas (infantryman, soldiers, warriors), forming a vast semicircle bristling with spears, stood motionless. The delegations of various peoples had been planted at the foot of the dais. A complete silence reigned. On Sundiata’s right, Balla Fasseke, holding his mighty spear, addressed the throng in this manner:

‘Peace reigns today in the whole country; may it always be thus . . . . I speak to you, assembled peoples. To those of Mali I convey Maghan Sundiata’s greeting; greetings tho those of Do, greetings to those of Ghana, to those from Mema greetings, and to those of Fakoli’s tribe. Greetings to the Bobo warriors and, finally, greetings to those of Sibi and Ka-ba. To all the peoples assembled, Djata gives greetings.

May I be humbly forgiven if I have made any omission. I am nervous before so many people gathered together.

Peoples, here we are, after years of hard trials, gathered around our savior, the restorer of peace and order. From the east to the west, from the north to the south, everywhere his victorious arms have established peace. . . .

In the world man suffers for a season, but never eternally. Here we are at the end of our trials. We are at peace. May God be praised. But we owe this peace to one man who, by his courage and his valiance, was able to lead our troops to victory.

Which one of us, alone, would have dared face Soumaoro? Ay, we were all cowards. How many times did we pay him tribute? The insolent rogue thought that everything was permitted him. What family was not dishonored by Soumaoro? He took our daughters and wives from us and we were more craven than women. He carried his insolence to the point of stealing the wife of his nephew Fakoli! We were prostrated and humiliated in front of our children. But it was in the midst of so many calamities that our destiny suddenly changed. A new sun arose in the east. After the battle of Tabon we felt ourselves to be men, we realized that Soumaoro was a human being and not an incarnation of the devil, for he was no longer invincible. A man came to us. He had heard our groans and came to our aid, like a father when he sees his on in tears. Here is that man. Maghan Sundiata, the man with two names foretold by the soothsayers. . . .’

Thereafter, one by one, the twelve kings of the bright savanna country got up and proclaimed Sundiata ‘Mansa’ in their turn. Twelve royal spears were stuck in the ground in front of the dias. Sundiata had become emperor. The old tabala of Niani announced to the world that the lands of the savanna had provided themselves with one single king. [Siphiwe note: According to Balanta elders, our Balanta ancestors were living in these lands of the savanna and we rejected such kingdoms and empire state structures because of the inequality that they inevitably produce. Thus, Balla Fasseke’s statement that ‘the lands of savanna had provided themselves with one single king’ must be taken with a grain of salt. Sundiata was definitely not the king of the Balanta]

When the imperial tabala had stopped reverberating, Balla Fasseke, the grand master of ceremonies, took the floor again following the crowd’s ovation. . . . Each people in turn came forward to the dais under Sundiata’s impassive gaze. . . . Sundiata got up and a graveyard silence settled on the whole place. The Mansa moved forward to the edge of the dais. Then Sundiata spoke as Mansa . . . .

‘Today I ratify forever the alliance between the Kamaras of Sibi and the Keitas of Mali. May these two people be brothers henceforth. In future, the land of the Keitas shall be the land of the Kamaras, and the property of the Kamaras shall be henceforth the property of the Keitas. May there nevermore be falsehood between a Kamara and a Keita and may the Kamaras feel at home in the whole extent of my empire.’

Sundiata took Tabon Wana’s spear and said, ‘Fran Kamara, my friend, I return your kingdom to you. May the Djallonkes and Mandingoes be forever allies. You received me in your own domain, so may the Djallonkes be received as friends throughout Mali. I leave you the lands you have conquered, and henceforth your children and your children’s children will grow up at the court of Niani where they will be treated like the princes of Mali.’

One by one all the kings received their kingdoms from the very hands of Sundiata, and each one bowed before him as one bows before a Mansa.

Sundiata pronounced all the prohibitions which still obtain in relations between the tribes. To each he assigned its land, he established the rights of each people and ratified their friendships. The Kondes of the land of Do became henceforth the uncles of the imperial family of Keita, for the latter, in memory of the fruitful marriage between Nare Maghan and Sogolon, had to take a wife in Do. The Tounkaras and the Cisses, Beretes and Toures were proclaimed great divines of the empire. No kin group was forgotten at Kouroukan Fougan; each had its share in the division. To Fakoli Koroma, Sundiata gave the kingdom of Sosso, the majority of whose inhabitants were enslaved. Fakoli’s tribe, the Koromas, which other call Doumbouya or Sissoko, had the monopoly of the forge, that is, of iron working. Fakoli also received from Sundiata part of the lands situated between the Bafing and Bagbe rivers. Wagadou and Mema kept their kings who continued to bear the title of Mansa, but these two kingdoms acknowledged the suzerainty of the supreme Mansa. The Konate of Toron became the cadets of the Keitas so that on reaching maturity a Konate could call himself Keita. . . .

Thus spoke the son of Sogolon at Kouroukan Fougan. Since that time his respected word has become law, the rule of conduct for all the peoples who were represented at Ka-ba.

So, Sundiata had divided the world at Kouroukan Fougan. He kept for his tribe the blessed country of Kita, but the Kamaras inhabiting the region remained masters of the soil.”

LISTEN TO A BALANTA HISTORIAN TELL THE ORAL HISTORY (IN ENGLISH)

My sons, thus have our Balanta ancestors been written out of history. Though living and present in these Savanna lands at the time, our Balanta ancestors were busy maintaining an egalitarian, non-state society that they preferred according to their spiritual Great Belief. It is a flaw of history to equate state-building with superiority and ignore people like our Balanta ancestors. This is how we have been written “out of history”. Nevertheless, we can reconstruct our history from this. Again, Balanta elders say that Malians revolted against the Balanta and that is why our ancestors left. They refused the domination of the Mali Empire, refused to pay taxes, and even conducted raids against the Mali oppressors. Consider this passage from the Epic of Sundiata:

“[Sundiata] restored in the ancient style his father’s old enclosure where he had grown up. People came from all the villages of Mali to settle in Niani. The walls had to be destroyed to enlarge the town, and new quarters were built for each kin group in the enormous army. . . . When reconstruction of the capital was finished, he went to wage war in the south in order to frighten the forest peoples. . . .

After a year Sundiata held a new assembly at Niani, but this one was the assembly of dignitaries and kings of the empire. The kings and notables of all the tribes came to Niani. The kings spoke of their administration and the dignitaries talked of their kings. Fakoli, the nephew of Soumaoro, having proved himself too independent, had to flee to evade the Mansa’s anger. His lands were confiscated and the taxes of Sosso were payed directly into the granaries of Niani. In this way, every year, Sundiata gathered about him all the kings and notables; so, justice prevailed everywhere, for the kings were afraid of being denounced at Niani.

Djata’s justice spared nobody. He followed the very word of God. . . . Each year long caravans carried the taxes in kind to Niani. You could go from village to village without fearing brigands. A thief would have his right hand chopped off and if he stole again he would be put to the sword.”

Finally, consider this from Nubia Kai, discussing in her new book, Kuma Malinke Historiography; Sundiata Keita to Almamy Samori Toure the first and last leaders of the Mali Empire from the 13th through the 15th centuries:

"Sundiata, the founder of the first and first emperor of Mali overcame a debilitating illness during his youth. He evaded the attempted murder initiated by his father's first wife Sassouma Beret, went into exile for several years with his mother Sogolon Conde and finally vanquished the despot [foreign name spoken] who had ruthlessly conquered and subjected the Manden kingdoms. Under his rule, the Manden kingdoms were reorganized into the Great Empire of Mali. He restored peace, order, justice and autonomy to the Mandinka kings and established alliances and solidarity with neighboring nations who were installed in the empire. [Sundiata's] greatest achievement which until recently was guarded in secrecy by a consensus of Mandinka griots was his abolition of slavery and the slave trade. His numerous conquests in West Africa were launched in order to enforce the oath of the Manden. The Edict officially banning slavery and slave trade in the empire.

Unfortunately, the slave trade and slavery was resumed 20 years after his death and apparently the national shame of the breaking of the oath compelled the griots to censure this significant event from the annals of Mali's official history, yet this effacement was public not private and initiated griots, the [foreign word spoken] were taught the history but had to swear never to reveal it.

[Foreign name spoken] who was the chief griot of Mali in the 1970s and 80s griot [foreign name spoken], made the decision to break the vow of silence and divulge this hidden history to a Malian historian, a modern Mali historian [foreign name spoken]. [Foreign name spoken] collected and published [foreign name spoken] [foreign words spoken]. Excuse my French for those of you who know the language right and I want to show you and talk about the oath of the Manden or it's also called the Manden Charter in the PowerPoint but I'm going to come back to that. . . . .Now this Manden Charter is as I said before, was a charter or an oath that was constructed at the beginning of the formation of the Mali Empire and with the information that came out, and this information came out in the 1980s, the secret history was revealed through [foreign name spoken].

Now scholars are trying to look, they have to kind of look again at the whole history of Mali because instead of some ruler Conte who was the enemy in the Epic of Sundiata Keita, he now becomes the hero or is a hero because he was the one who came up with the idea to end slavery in the Mali Empire and what he did he tried to call the Mandinka people to arms against [foreign name spoken] and against the Moor's [assumed spelling] and other Mandinka who were also trading in slaves.

Now this is 300 years before the transatlantic slave trade and it was pretty bad even at that time and I'm not going to go into all the details but if you want to read [foreign name spoken] text that, again, where he's recording [foreign name spoken] you can get the text, but they have not been translated. They're still in French. Anyway, [inaudible] comes up with the idea and when the Mandinka refuse to go along with him and ending slavery because some of the major leaders in the Manden were slavers.

They were big slavers and slave traders, so they refused. So, [foreign name spoken] this is when he launches his attack. He attacks the Mandinka people, kills 9 of the kings, impales their bodies on spikes, makes furniture out of the skins of his enemies and literally sells the people into slavery. That was his response when they refused to end slavery. That's why in the secret history he's known as a sacred despot. It sounds rather oxymoronic but he's called a sacred despot because the idea to end slavery and the slave trade was really [foreign name spoken] idea.

So, finally and you probably know the story because the Epic of Sundiata has now become part of the literary canon now, you're reading in colleges almost everywhere. You know the story how he's away in exile because his step-mother is trying to kill him. He's away and the envoys are sent to get him and when comes back he goes into, he has this war with [foreign name spoken] and eventually vanquishes him and then he becomes the emperor. But what happens is, just before his mother passes away, his mother is Sogolon Conde who tells him, look they're going to ask you to be the emperor but before you accept the position of emperor I want you to abolish slavery and the slave trade in the Mali Empire forever and of course he agreed to do this and so this is what he did.

This is why he goes onto this conquest of the outlying nations like the Jolof and [foreign name spoken] and other parts around Mali because he knew as long it continued in the outlying areas it was going to infiltrate back into the Manden proper. So, he creates an empire that was slave free, you know, an empire where slavery was forbidden and where the trade was forbidden and this is how the Charter goes.

The hunters refers to it because Sundiata was a hunter. "The hunters declare all human life is one life. It is true that one life may appear to exist before another life but one life is not more ancient or more respectable than another life.

Here we have the truth, but for the twenty years during Sundiata’s reign, the Mali Empire were the biggest slave traders before and after.

Thus my sons, the praise and honor that the kingdom of Mali receives by historians and ignorantly repeated by people today, is based on the idea that such state superstructures are an indication of superiority when, in fact, our Balanta ancestors recognized that the states like Mali created inequality and violated the Great Belief, and thus were resisted. We do not view the Empire of Mali as a point of pride because it was oppressive and continuously tried to dominate and enslave us. Unfortunately, it was during this period that the people known as “Portuguese” arrived.

MORE SERIOUS BLACK HISTORY

Main Slave Markets In West Africa Before the Europeans: Kano, Gao, Timbuktu and Djenne. It is worth noting, as Nehemia Levtzion & Randall L. Pouwels do in The History of Islam in Africa, that:

"Because Islam spread to West Africa from North Africa, Muslims there followed the Maliki school of law dominant in North Africa. On the other hand, in East Africa, where Islam came from the Arabian Peninsula, Muslims followed the Shafi’I school of law that prevailed in Arabia. Both regions, however, were exposed to the influence of the Ibadiyya sect. Ibadi merchants opened up trade across the Sahara and were among the first Muslims who reached western Sudan – as early as the eight and ninth centuries. But whatever converts they had made were reconverted to Maliki Islam by the eleventh century.

Soon after they had defeated the Byzantine imperial forces in the middle of the seventh century, the Arabs gained control over coastal North Africa. But for some time, the Arabs failed to impose their authority over the Berber tribes of the interior. Successive revolts of the Berbers, that forced the Arabs to withdraw, were referred to as ridda, the same term used when Arab tribes deserted the young Muslim community after the death of the Prophet. . . .

The next phase of the Berbers’ resistance to Arab rule occurred when Islam, throughout adherence to heterodox sects, first the Ibadiyya and then the Isma’iliyya. The Almoravids finally secured the victory of Sunni-Maliki Islam in the eleventh century. Under their Almohad successors, Islam in the Maghrib became imbued with the mysticism of the Sufis, who became the principle agents of Islamization in North Africa after the twelfth century.

Berber speaking nomads reached the southern Sahara and touched the Sahel in pre-Islamic times. They were well positioned to mediate Islamic influences between the Maghrib and the Western Sudan (known to the Arabs as ‘Bilad al-Sudan’). As Berber nomads occupied both shores of the Sahara, the dividing line between ‘white’ and ‘black’ Africa . . . was where the desert meets the Sahel, and where Berber-speaking nomads interacted with the Sudanic sedentaries. Along this line they cooperated in creating the termini of the Saharan trade. Today, this dividing line cuts across the modern African states of the Sahel – namely, Senegal, Mali, Niger, Chad and the Sudan. In all these states, except the Sudan, political power is with the black people of the south; it is also only in the Sudan that the dividing line is not only an ethnic but also a religious frontier.

As early as the eleventh century, Manding-speaking traders, ancestors of the Juula, traveled between the termini of the Saharan routes and the sources of the gold. They created a ‘commercial diaspora’, based on a shared religion as well as a collective language. A common legal system – the law of Islam (shari’a) – even if not strictly observed, contributed to mutual trust among merchants in the long -distance trade. Conversion to Islam became necessary for those who wished to join commercial networks. Though merchants opened routes and exposed isolated societies to external influences, they did not themselves engage in the propagation of Islam.

Conversion to Islam was the work of men of religion who communicated primarily with local rulers. The latter often became the first recipients of Islamic influence, and indication to the importance that states had in the process of Islamization. Thus, for some time Muslims lived under the hospitality of infidel kings, who generally were praised by Muslims for their benevolence toward the believers. This was the situation in eleventh century Ghana as is in nineteenth-century Asante. The process of Islamization advanced when Muslim clerics helped African kings to overcome severe droughts, as in the case of eleventh century Malal, or to secure victory, as in fourteenth-century Kano and sixteenth century Gonja. But, because only the king and his immediate entourage came under the influence of Islam, the ruling aristocracy adopted a middle position between Islam and the traditional religion, patronizing both Muslim divines and traditional priests. It was through the chiefly courts that Islamic elements filtered the culture of the common people. The symbiotic relations of Islam with the traditional religion has been illustrated in a novel by Ahmadou Kourouma, who remarked that everyone publicly proclaimed himself a devout Muslim, but privately feared the ‘fetish’. Muslim clerics who rendered religious services to Islamized chiefs became integrated into the sociopolitical system of the state by playing roles similar to those of traditional priests. Like traditional priests, Muslim clerics were politically neutral and could therefore act as peacemakers. Mosques, like shrines, were considered sanctuaries. . . .

In the great kingdoms of the Sahel, with international trade, Muslim centers of learning and close connections with the Muslim world, the kings developed greater commitment to Islam. But even these kings, like Mansa Musa of Mali and Askiya Muhammad of Songhay, were unable to relieve the monarchy of its pre-Islamic heritage. . . .

Around Lake Chad, the trade of Kanem to North Africa was mainly in slaves. As a result, Islam did not spread to the lands south of Lake Chad, which remained hunting grounds for slaves. . . .”

In the words of our great Pan African historian John Henrik Clarke,

“The African accepted the religious side and the spirituality, and Islam said something to the African that it did not say to the Arab and that it still says something to the African that it is not saying to them . . . . It was from Arabia that the religion came out, swept over into North Africa, and had its rapid growth. . . . The Muslim armies swept across most of Northern Africa. There was a little resistance from the Berbers – these are the relatives of the Arabs who had arrived much earlier. This resistance didn’t last too long. But this resistance died down, and Islam swept into the Western Sudan and began to convert Africans. . . . "

Many people, like the Balanta ancestors, living in Ta-Nihisi (Nubia/Kush/Sudan) began moving westward when people started abandoning the Great Belief and choosing leaders. By the time of Menes in 3100 BC, many had already left. Some went north into Ta-Meri, and some went west following the Darb el-Arbeen trade route from Selima to El Fasher in Darfur, a journey of about 20 days (600 miles) and from there, all the way to Lake Chad, where some of their older ancestors had already settled 10,000 years earlier! In this region different groups of people, including the Balanta, settled again for almost 3,000 years. When foreign invasions pushed more and more people, both Nilotic and Afro-Asian mulattoes, south into Lower Nubia, Upper Nubia and Southern Nubia, many of those people, due to population pressures and conflicts, began migrating west following the same Darb el-Arbeen trade route to El Fasher in Darfur. When they arrived, they found people already living there!

Over a period of time, the Sayfuwa of the ruling Magumi class established the Duguwa city states that gained control of the Sa-u alliance of settlements. Later, another group of people, the Tumagera, also affiliated with the Magumi ruling class, migrated from Ethiopia and Meroe west into the Kordofan region and then into the area between the Nile and Lake Chad and established the Tungur Confederation. . . .

According to Moustafa Gadalla,

“A decisive moment seems to have occurred in [Sa-u] history, when the early sites were abandoned except at the spirited (sacred) groves, and the population regrouped itself in larger settlements, each enclosed within a defensive wall from the 11th century onward. The defensive walls were built to protect them from the Islamic jihads, which intended to convert, kill or enslave them.” This is why another historian, Chancelor Williams writes, “The new fringe states of Darfur, Wadai and others under black Muslims offered no place of refuge for those whose very reason for flight was to maintain their own racial identity, dignity and religion. . . .”

John Jackson reminds us in Introduction to African Civilizations,

“The Soninke rulers built up an empire by subduing neighboring tribes. This was comparatively easy, since the Ghanaians had fine weapons and tools of iron, and their neighbors did not. Besides iron, Ghana possessed another source of wealth that made it a power to be reckoned with, namely a seemingly inexhaustible supply of gold. . . . "

Gadalla continues:

“The Empire of Ghana started out as a kingdom, then annexed other kingdoms, and, like many other kingdoms of the past, evolved into an empire. . . . The Soninkes spoke the Mande language, and in that tongue, Ghana meant ‘warrior king’, and was adopted as one of the titles of the King of Wagadu. Another title of the king was Kaya Magha (‘king of gold’), in allusion to the vast gold treasures of the country. As the fame of the Soninke warrior kings, or Ghanas, spread over North Africa, the people there referred to both the king and the nation over which he ruled as ‘Ghana’. Early Islamic merchants, most of them from Syria, followed the soldiers and administrators into northern Africa. Later, as stability was assured and wealth increased, traders were drawn to the regions of sub-Sahara Africa. Interior trade routes were utilized, and the camel, which had been in general use in North Africa since before the 3rd century, provided the means for traversing the desert. . . . By the 10th century, a number of major trans-Saharan routes had been developed.

The Arab conquest of North Africa, by the early 8th century CE, concluded with lightning success. In a matter of months, a strip of territory, 100-200 miles deep, was under Arab control – all the way from the borders of Egypt to the Atlantic coast.

The North African and Arabian slave trade was vigorous, and the demand for slaves was high. Islamic law forbade the enslavement of free Moslems but tolerated the continued enslavement of peoples who converted after their capture. In the years of Islamic conquest, the pastoral Berber people had provided the bulk of these slaves. The larger part of the population north of the Atlas Mountains became converts to Islam and therefore could not legally be enslaved.

Starting in the 10th century CE, in order to keep the supply up to the demand, the Arab traders conspired with the nomad Berbers to organize raids, under the guise of Islamic jihads, into neighboring provinces where traditional African religions were practiced. These raids, more than anything, caused many people to declare conversion to Islam prior to being captured, to avoid the horrible raids of killing, kidnapping, enslaving and family break-ups. . . .

Because traditional ancient Egyptian and African religions don’t have a doctrine and are not mobilized in a cult-type camp with rules and regulations, they accept everyone’s right to believe in any way they wish. The Arabs/Moslems enjoyed this right when they settled among the peaceful people. However, the native people became a victim of their own charity.

In order to penetrate the society, Moslem clerics preached ‘social injustice’, a slogan intended to start a class warfare. . . . The preachers of ‘social injustice’ were behind the largest human enslavement in the history of mankind.

Another tactic was for the Moslem/Arab traders to help one side or the other in local disputes, i.e. to get a foothold, and then betray. Divide and conquer.

Though many Moslems lived in Wagadu (ancient Ghana), worked there, and even served the King, the tolerant people treated them fairly and in a friendly way. By 1050, a powerful new force swept through West Africa. A Moslem preacher named Ibn Yacin founded his Almoravid sect, a fanatic group of Moslems. The Almoravids, however, did not return the Ghanaian’s religious freedom in kind.

One of the Almoravids’ targets was Wagadu, whose Kings had repeatedly refused to convert to Islam.

The Islamic doctrine calls on Moslems to spread Islam, even by force if necessary. As a result, any Moslem with a superior arm can force his religion by killing others. The unarmed people have no choice but to convert to Islam or die. This self-righteous Moslem may choose instead to enslave any and all members of a non-Moslem family. Spreading Islam by ALL means is not an option, but a duty required by the Islamic doctrine.

There were also sanctions for pursuing the jihad, or holy war, against those who had not been converted. Those who die in battle against non-Moslems, would die in a holy cause.

Each of these Islamic jihads had the same process. Just like any terror campaign, they required financing and hiring of mercenaries. All these terror campaigns started at the beginning point of Islam, i.e. Mecca. The story is the same all along the 2000-mile (3200 km) Sahel. For about 1000 years – a Moslem cleric, or leader, living in Africa, goes to Mecca, gets financial support, and is assigned as a ‘Moslem deputy caliph’ in his African region. He returns to declare Islamic jihad and supplies his masters with more slaves.

It always started with the usual intimidation, a (Moslem) gang will deliver a message to the leader of the peaceful non-Moslem group, to embrace Islam. Once people refuse and/or ignore this unsolicited intimidation, then as shamelessly stated in the Tarikh es Soudan (Soudan Chronicles), the Gangsters declared that it is:

‘Their duty is to fight them and straightaway, the Moslem fighters launched war against them, killing a number of their men, devastating their fields, plundering their habitations, and taking their children into captivity. All of the men and women who were taken away as captives were made the object of divine benediction [converted to Islam].’"

MORE HONEST SCHOLARSHIP NEEDS TO BE DONE ABOUT THE ISLAMIC JIHADS THAT TERRORIZED AND ENSLAVED THE VARIOUS FREE AND INDEPENDENT AFRICAN PEOPLES WHO WERE LIVING IN WEST AFRICA BEFORE THE ISLAMIC INVASIONS. WE ALREADY KNOW ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY OF SANKORE AND SUCH STUFF ABOUT THE EMPIRES OF GHANA, MALI, AND SONGHAY, BUT THE OTHER HALF OF THE STORY IS NOT BEING TOLD.