The Balanta B’urassa History and Genealogy Society in America organized events on two continents to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of Amilcar Cabral’s Meeting with African Americans in New York, October 20, 1972 in which he gave the speech, “Connecting the Struggles: An Informal talk with Black Americans”.

Watch the Premiere at 7:00 PM EST on October 20

https://youtu.be/6_YREg6hbdo

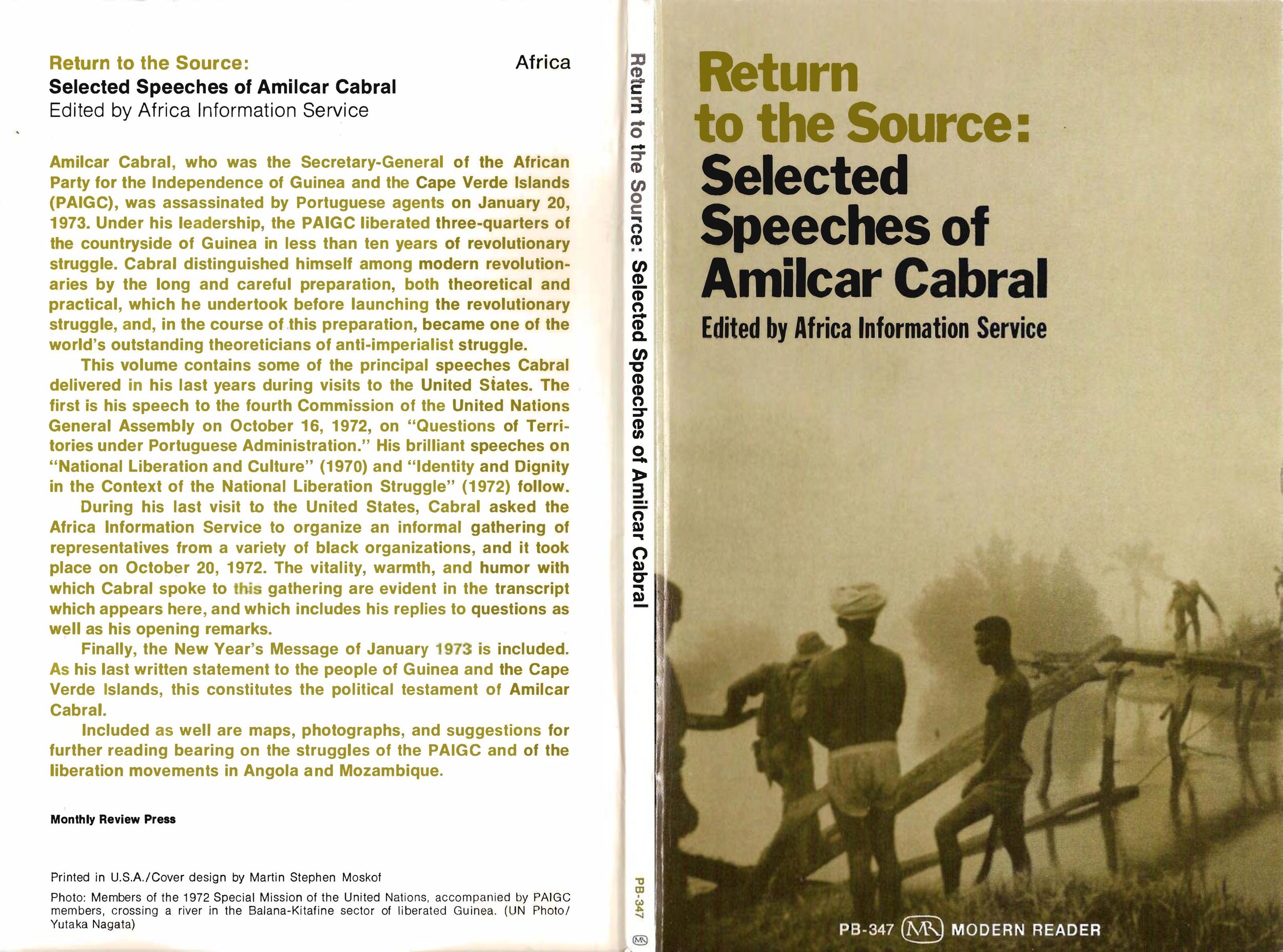

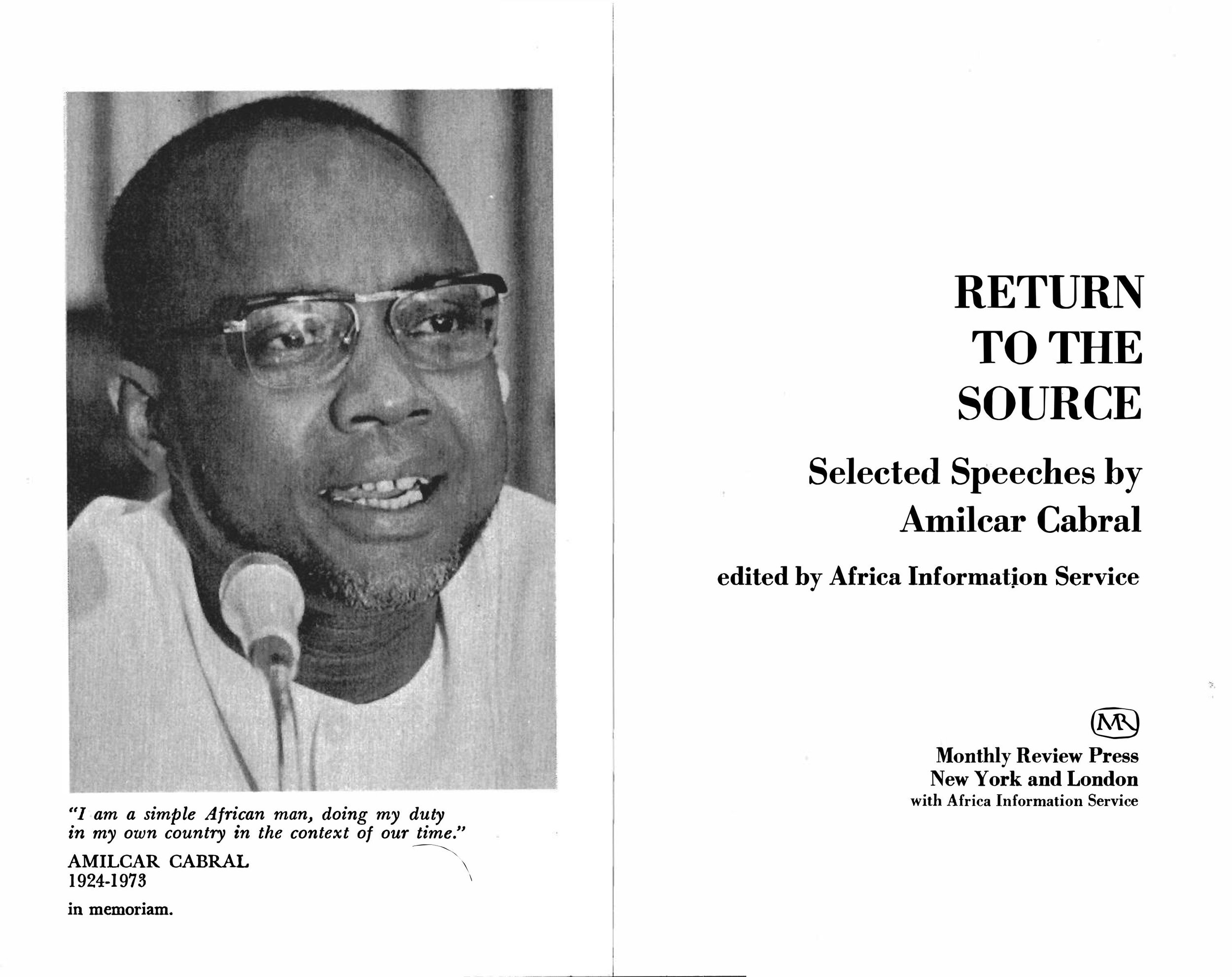

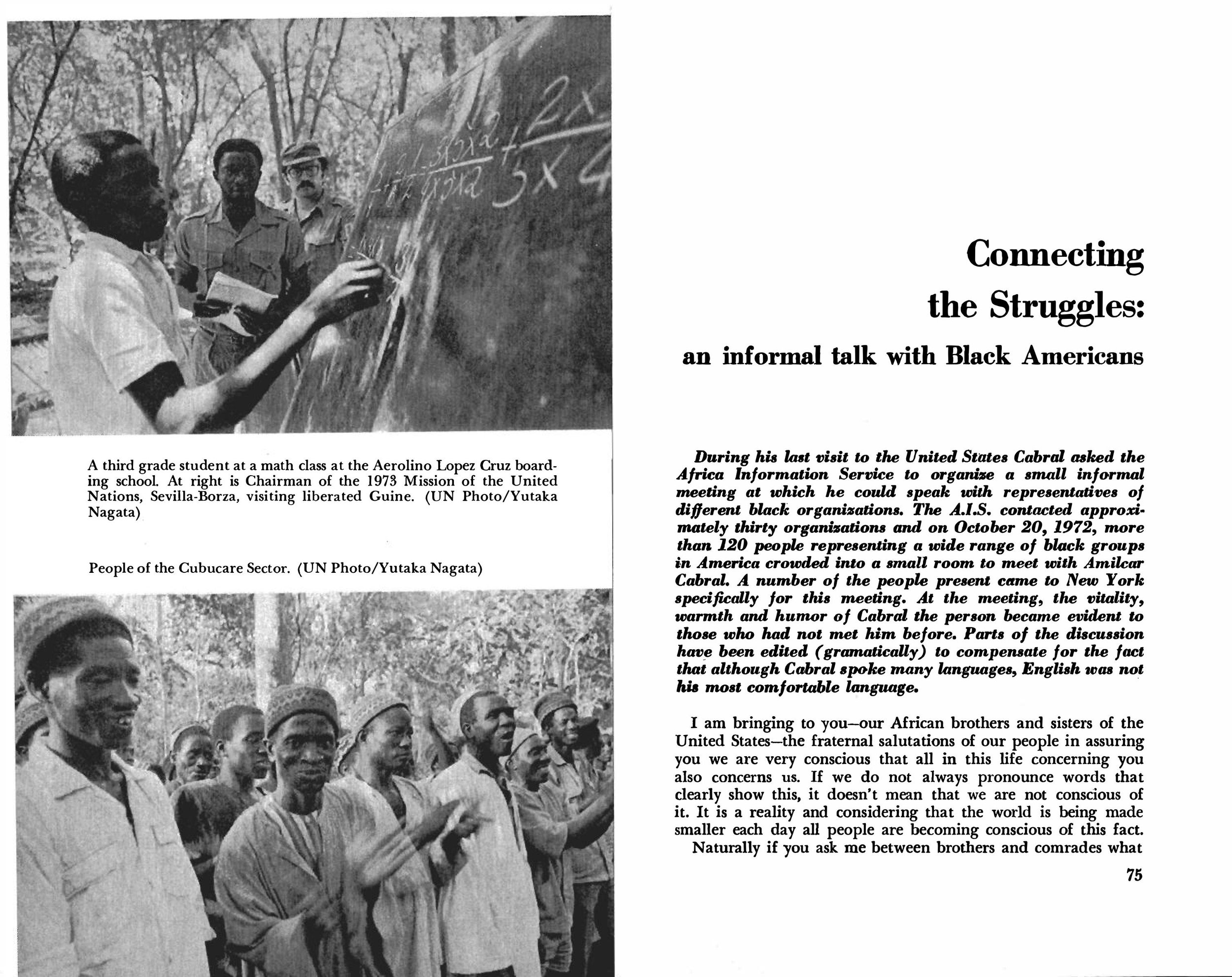

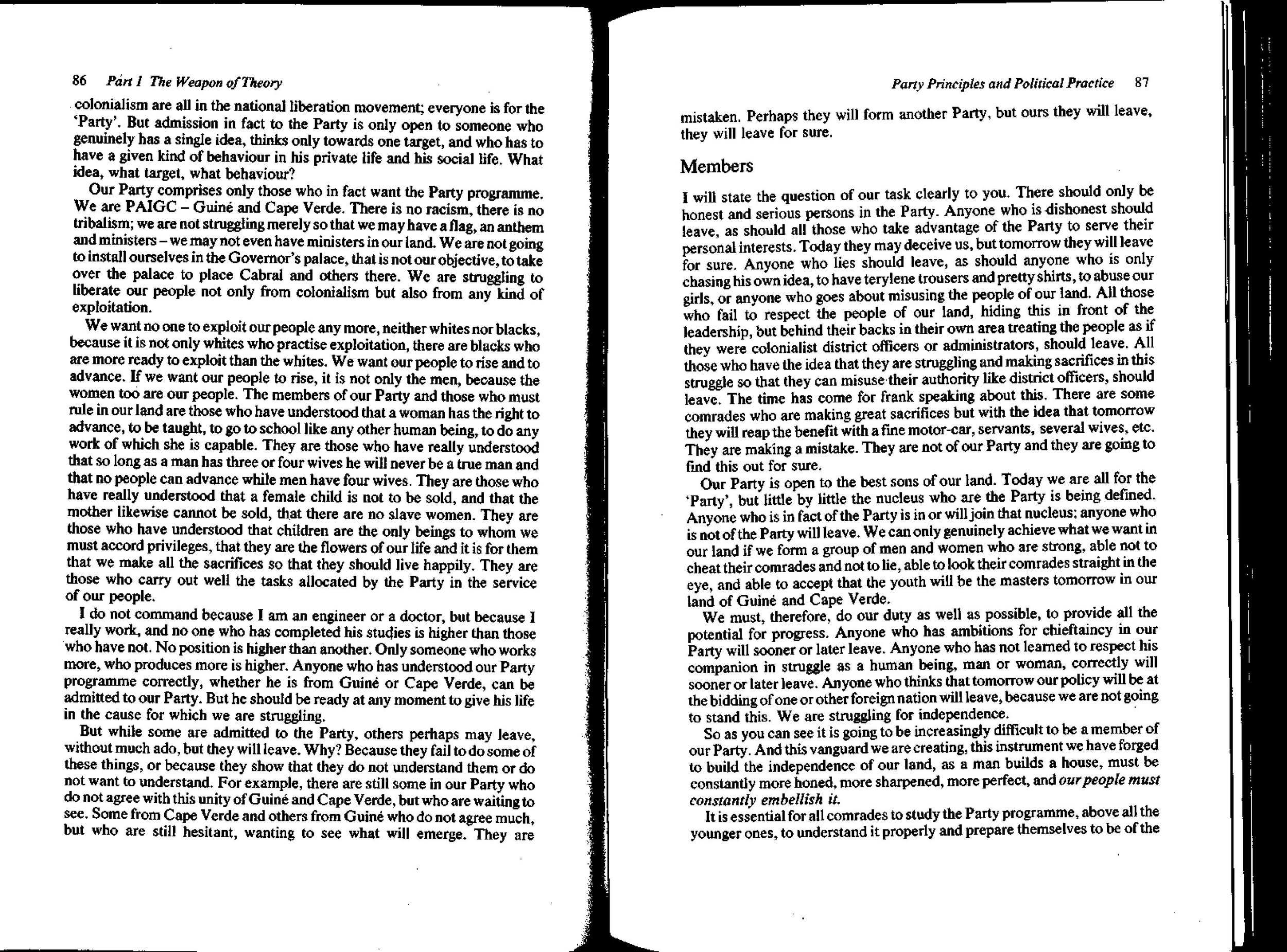

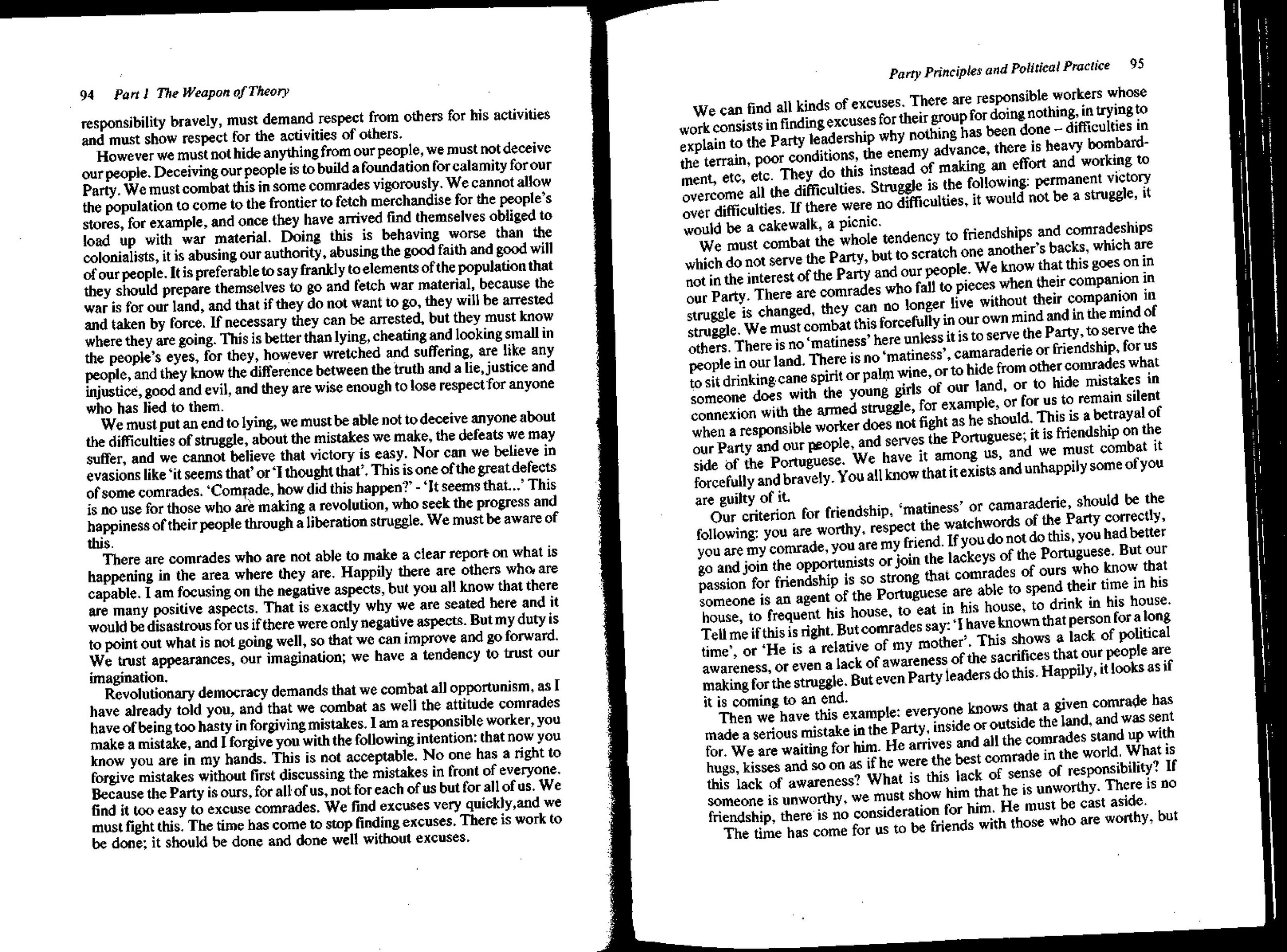

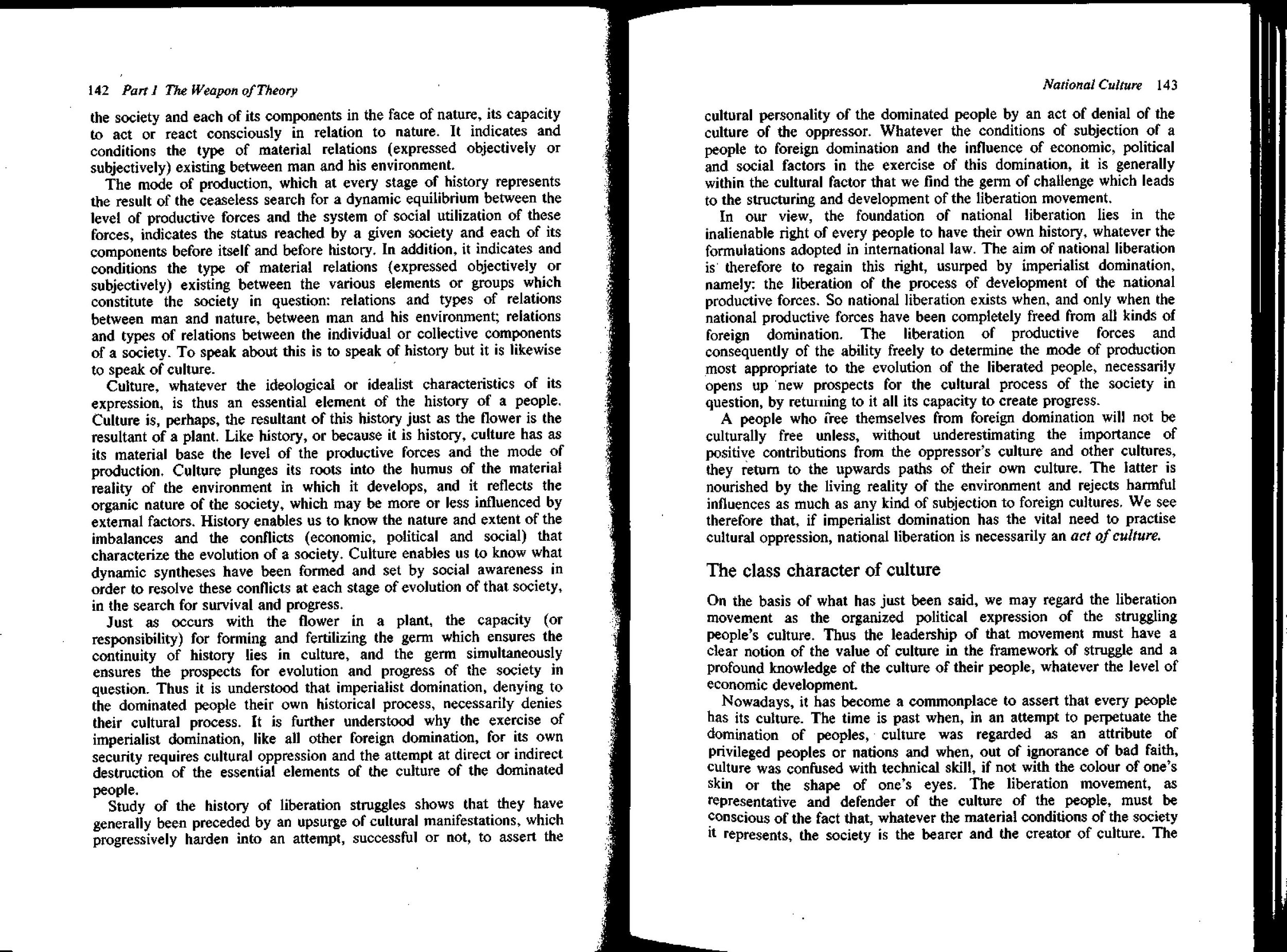

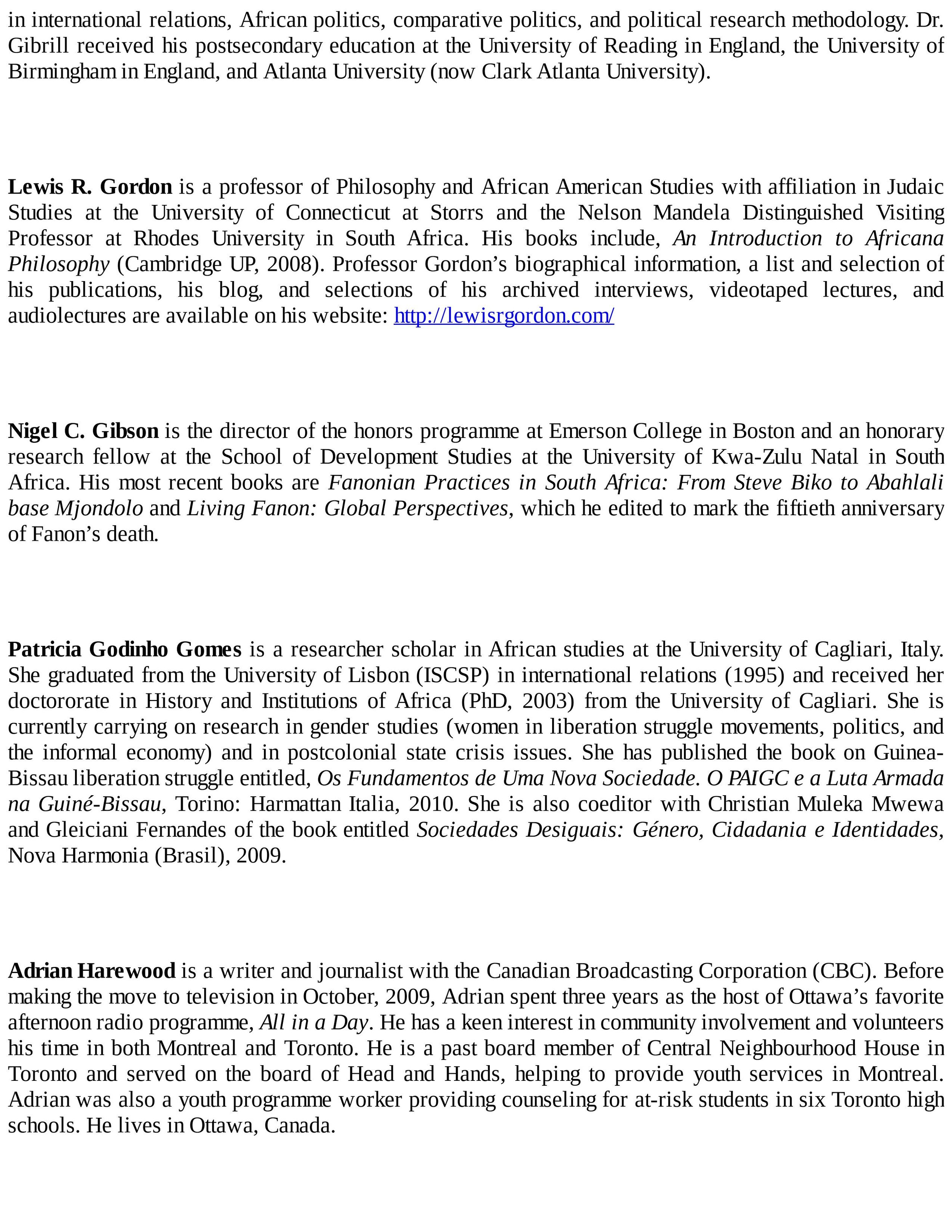

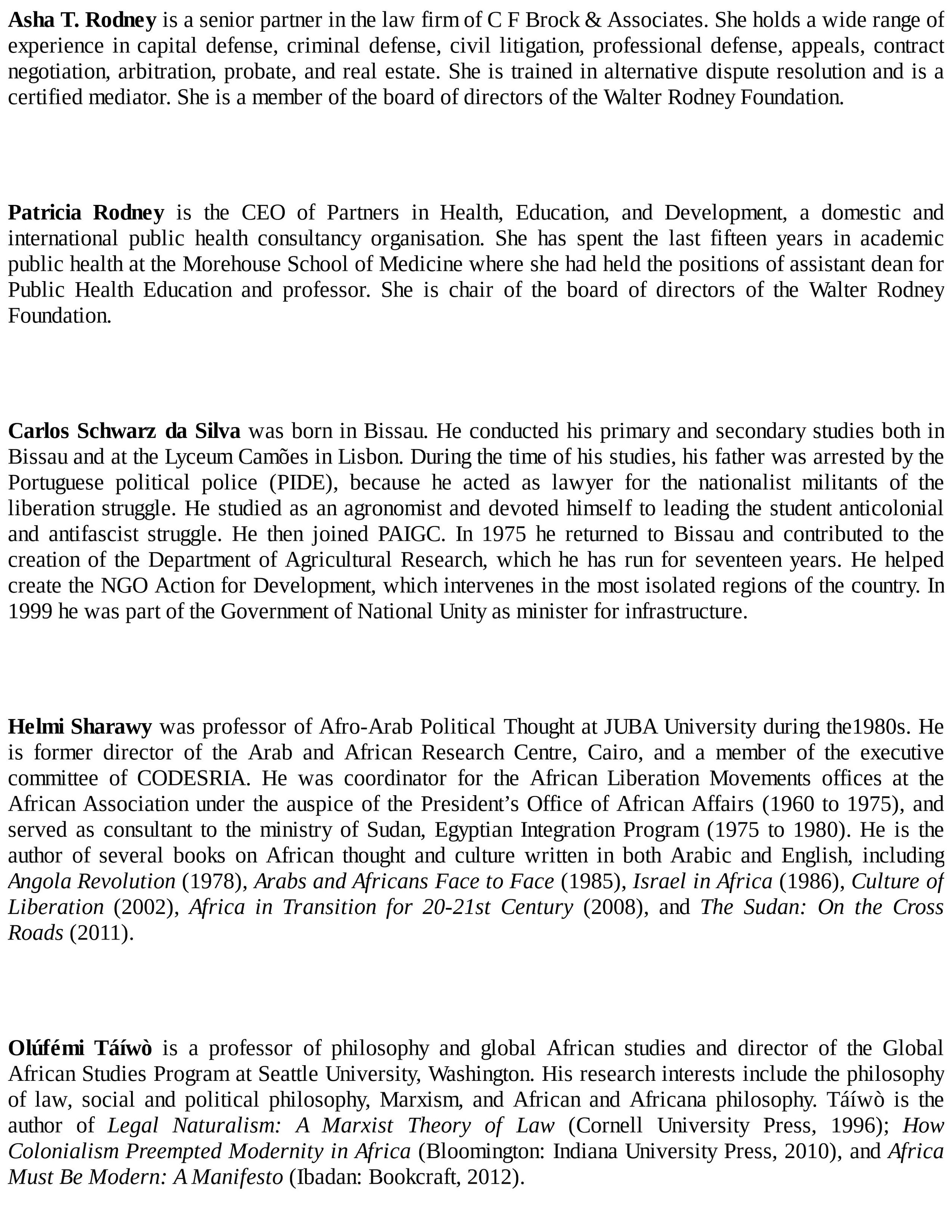

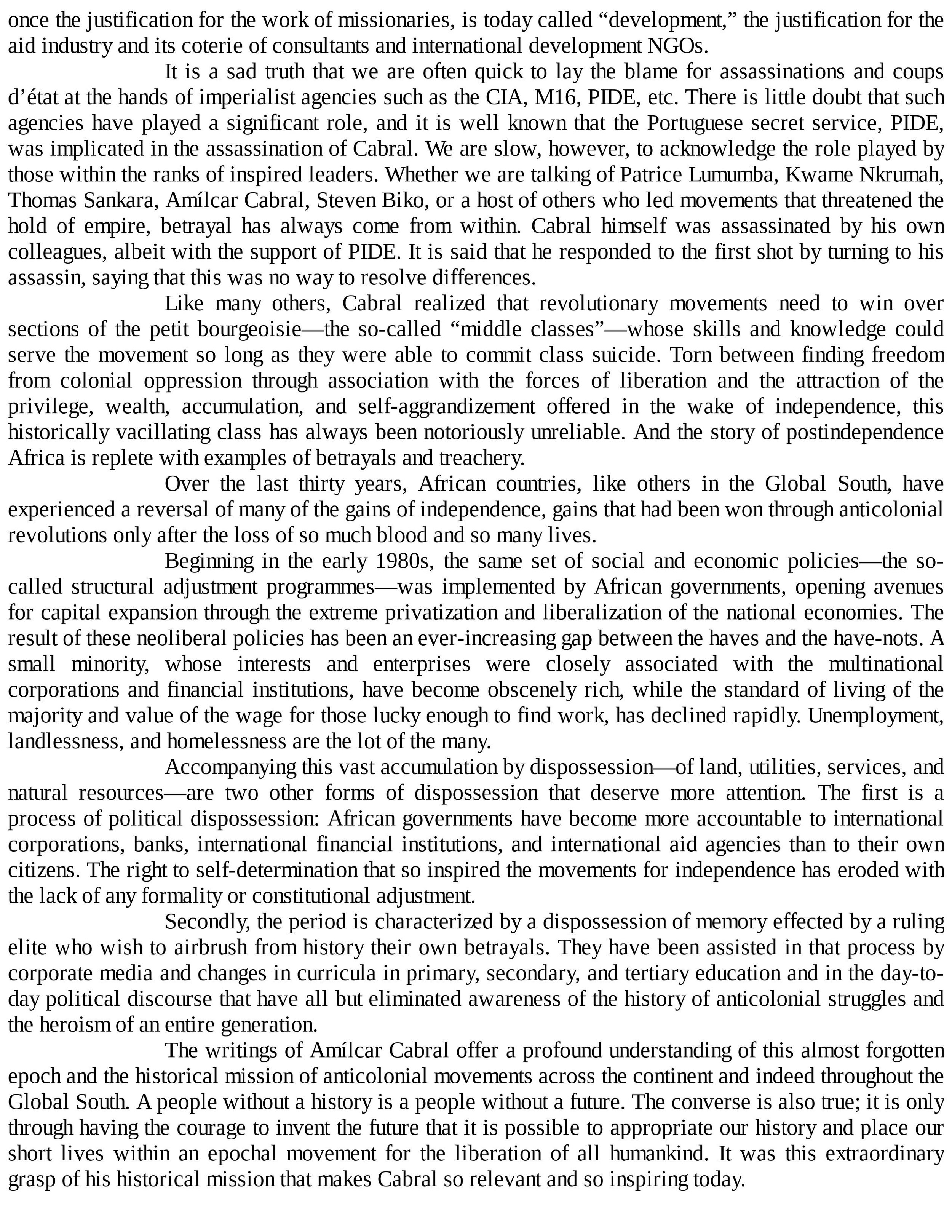

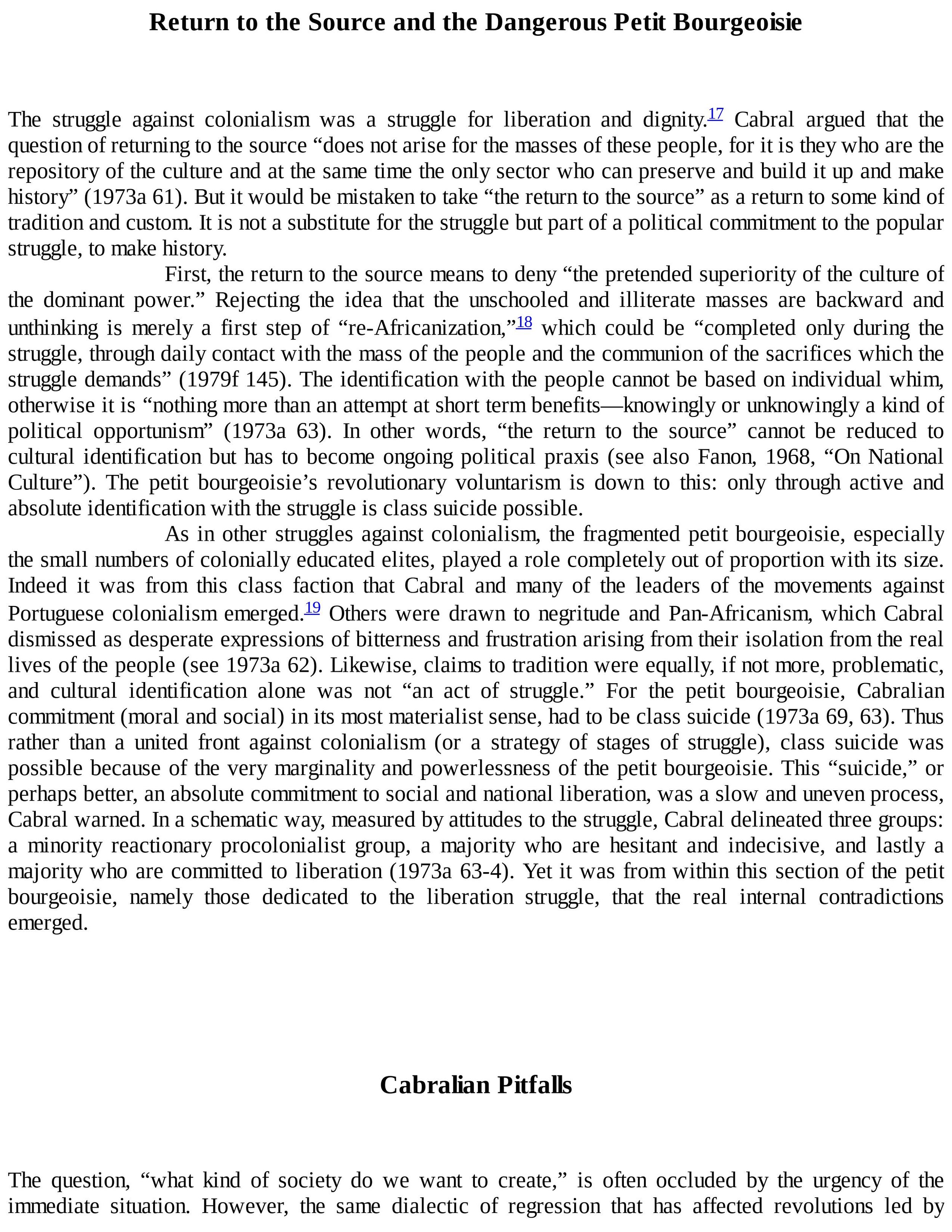

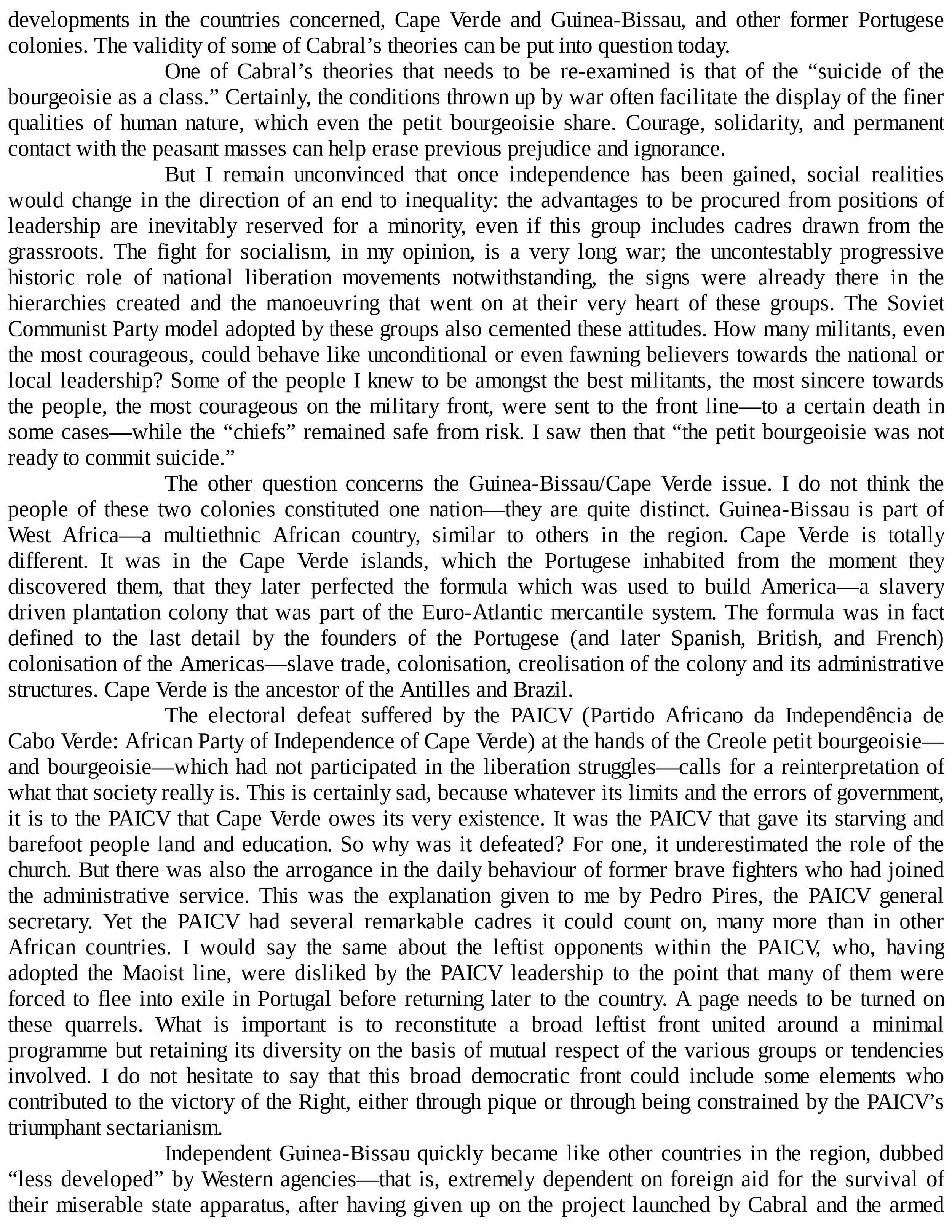

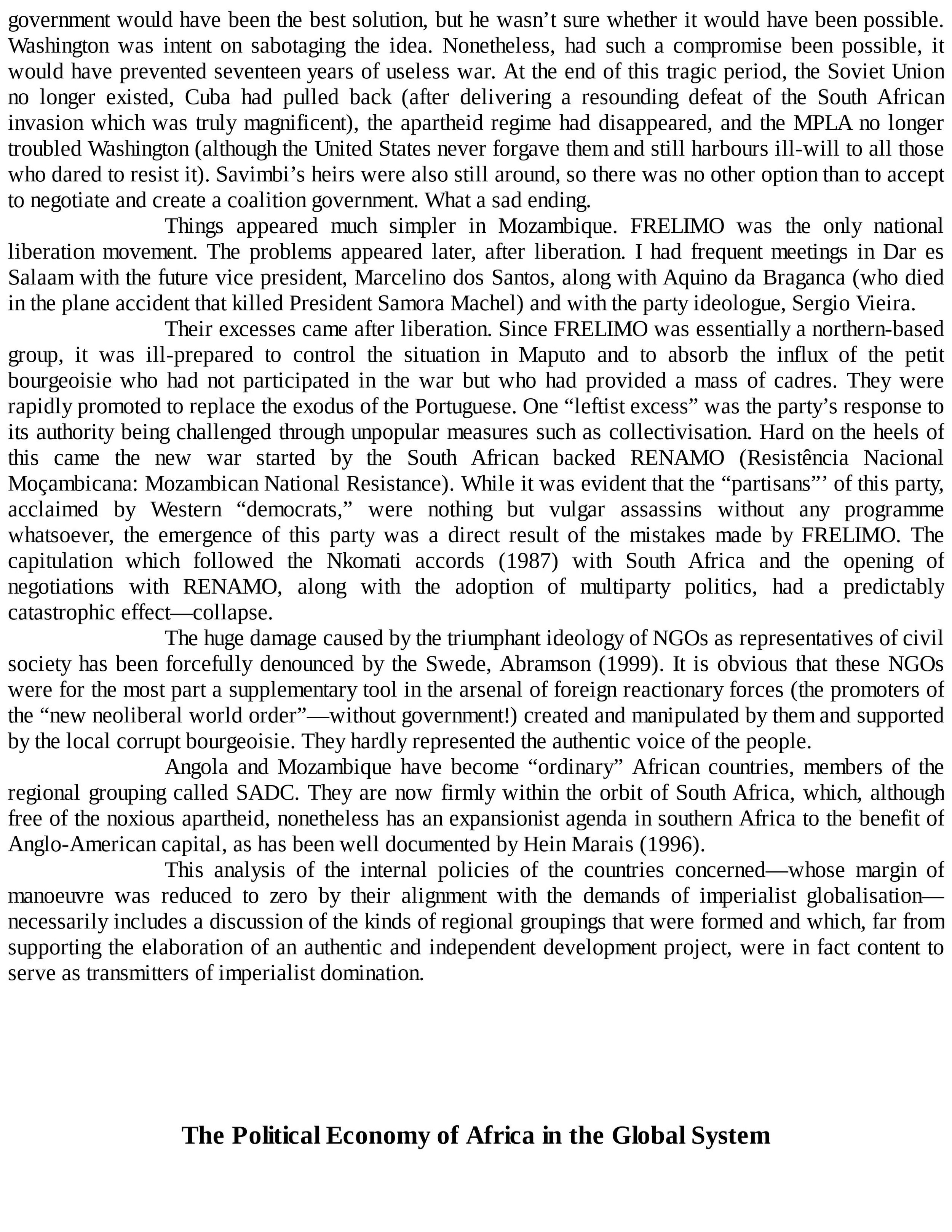

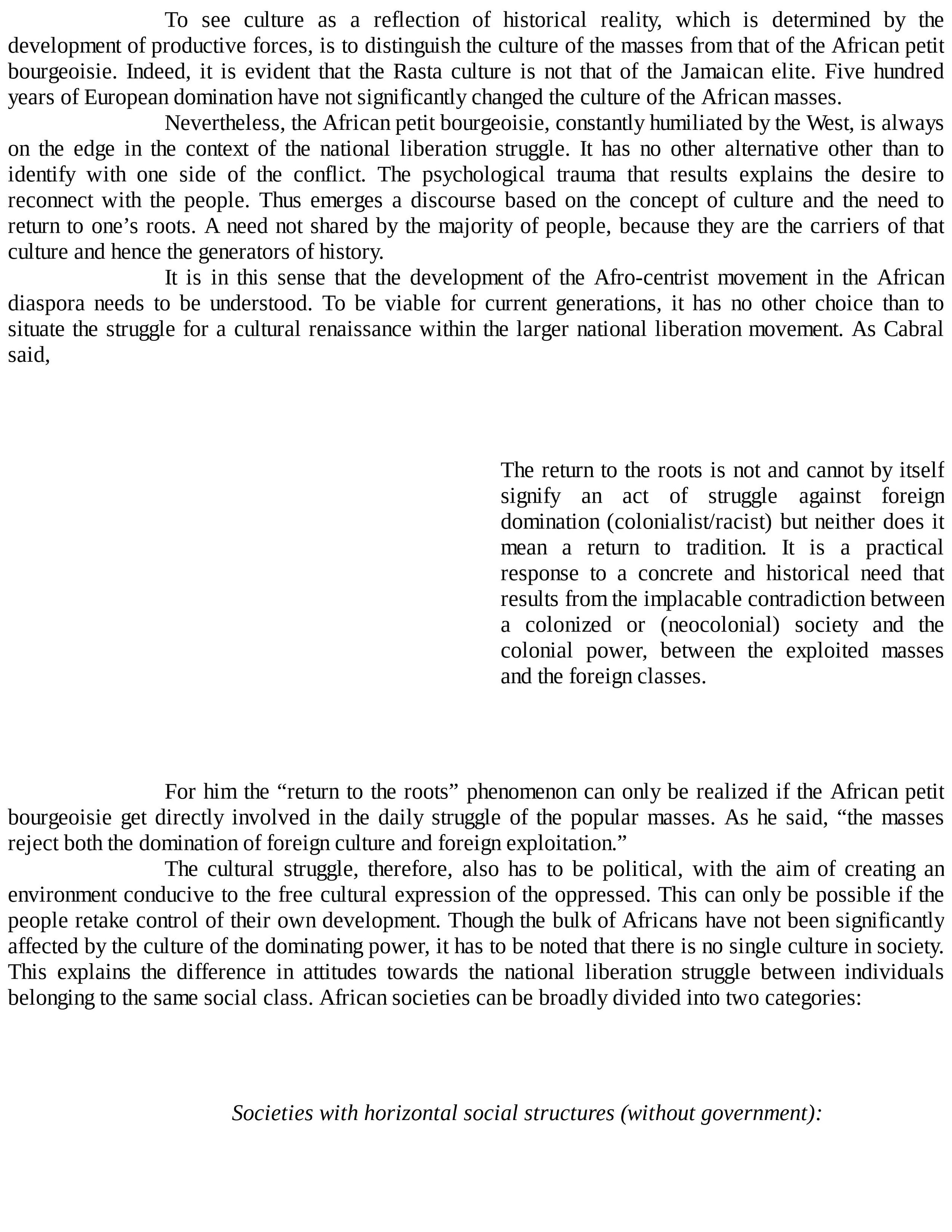

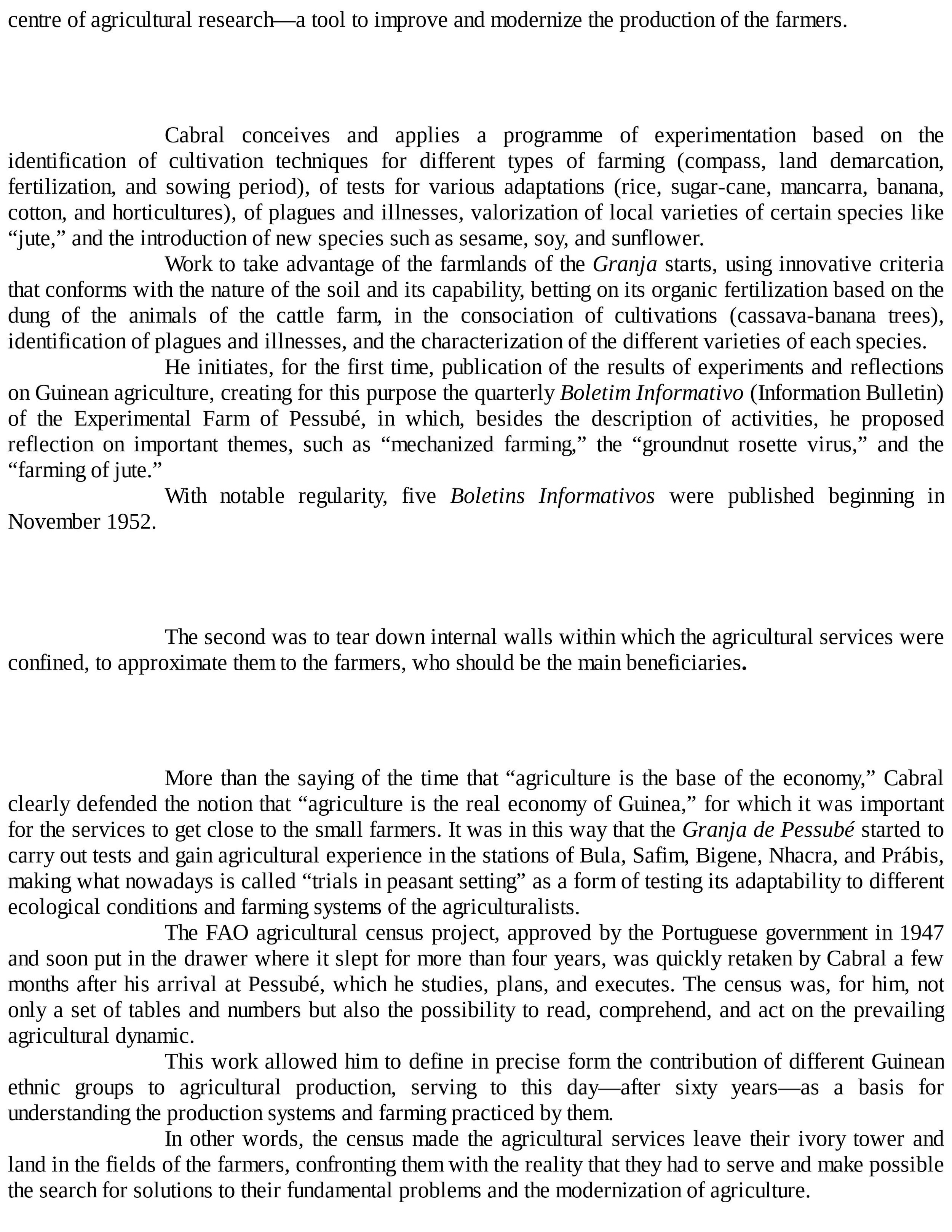

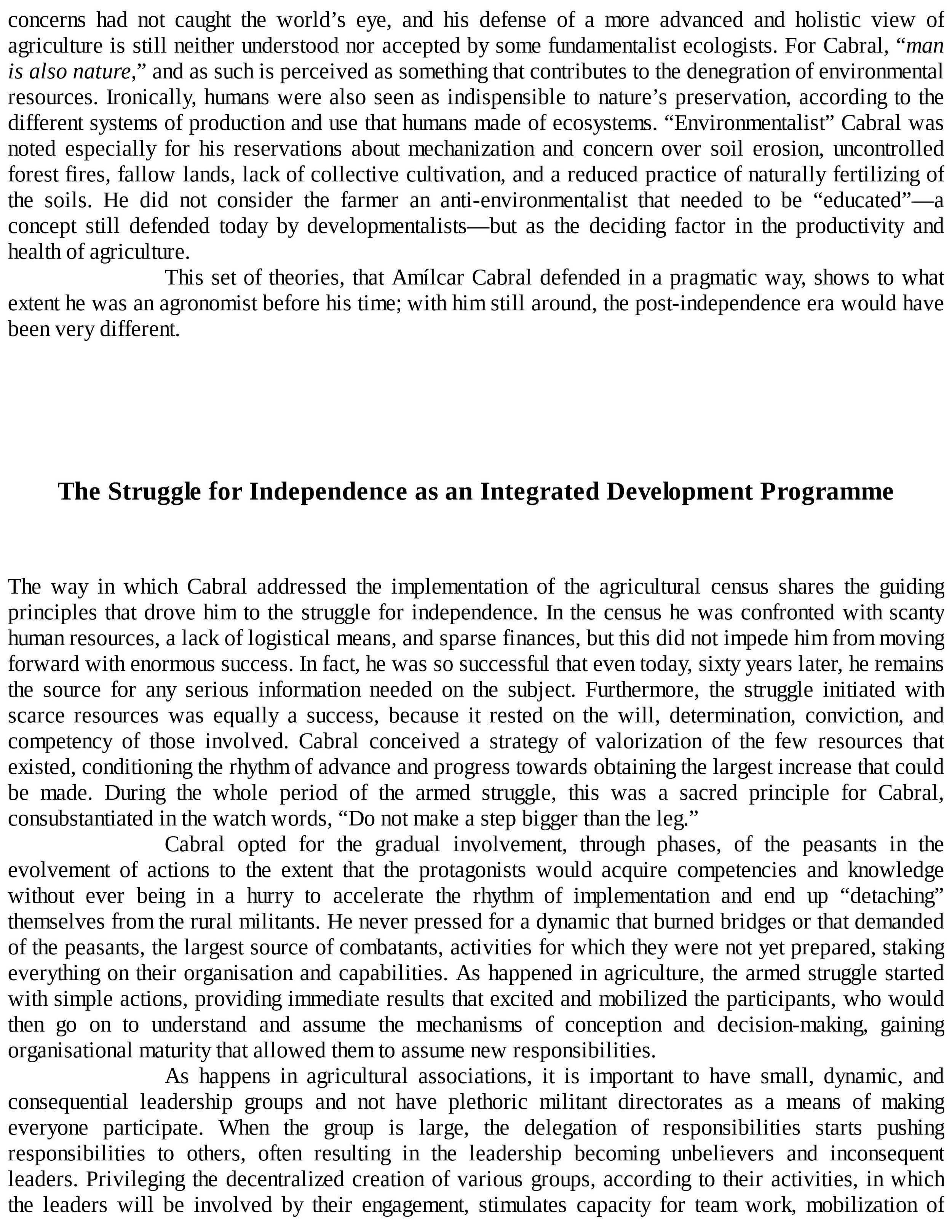

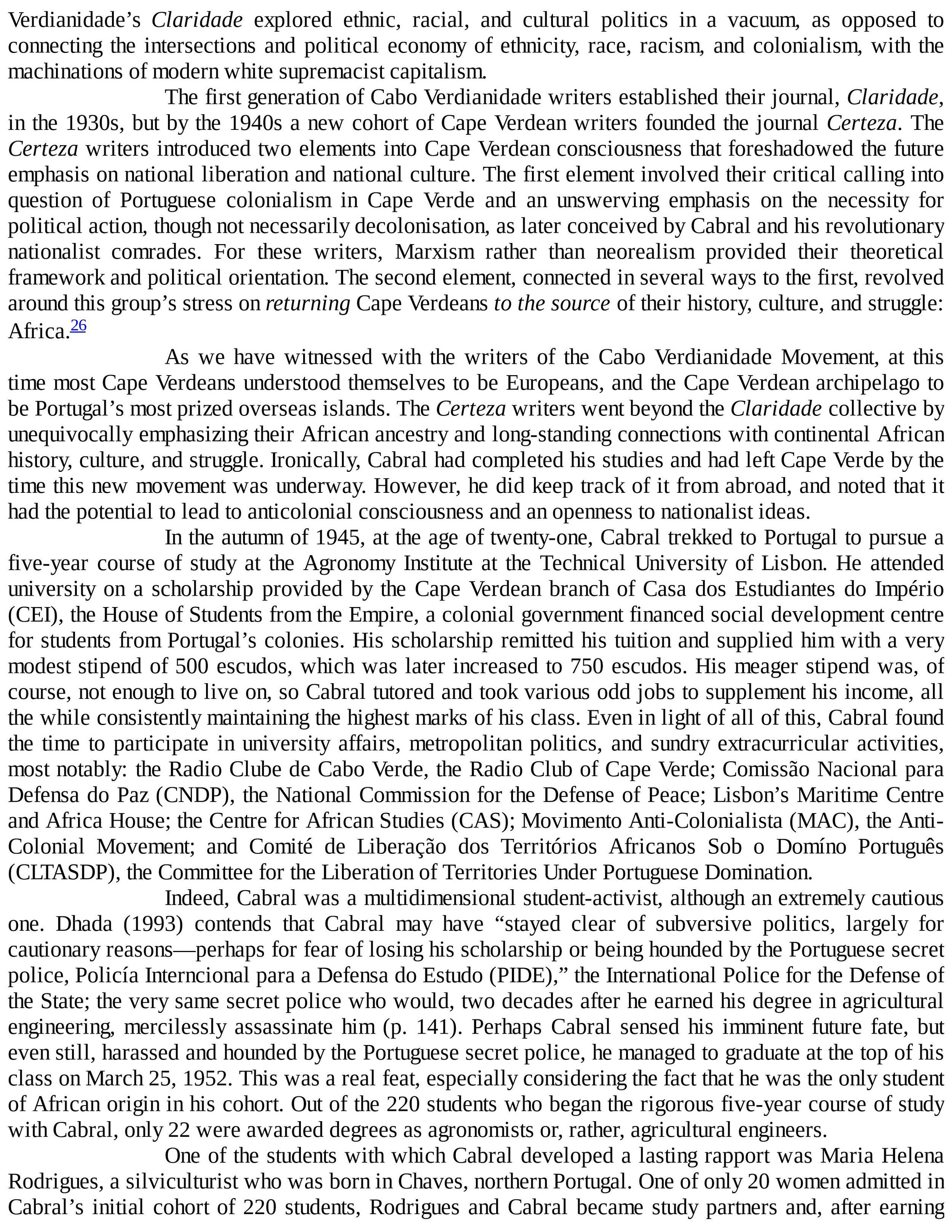

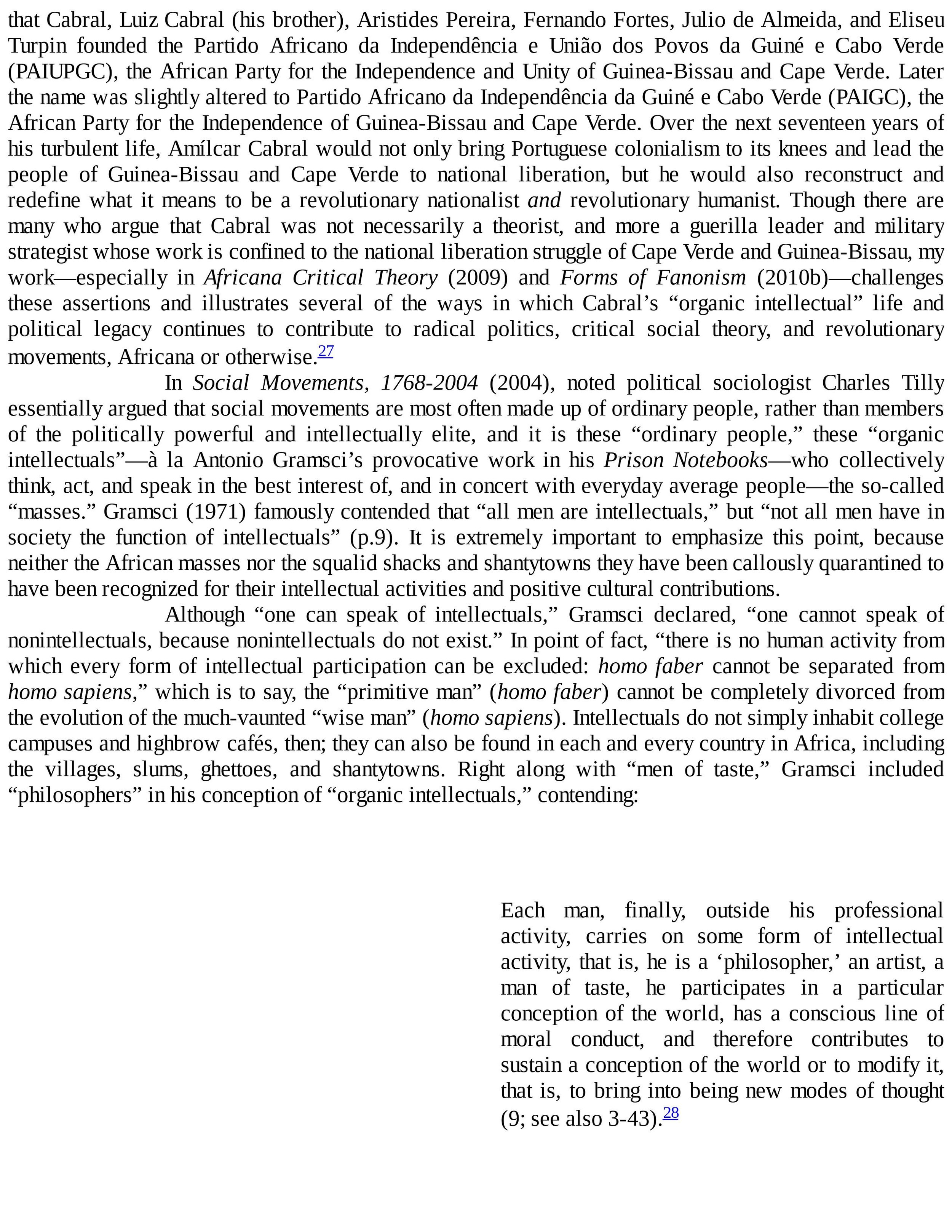

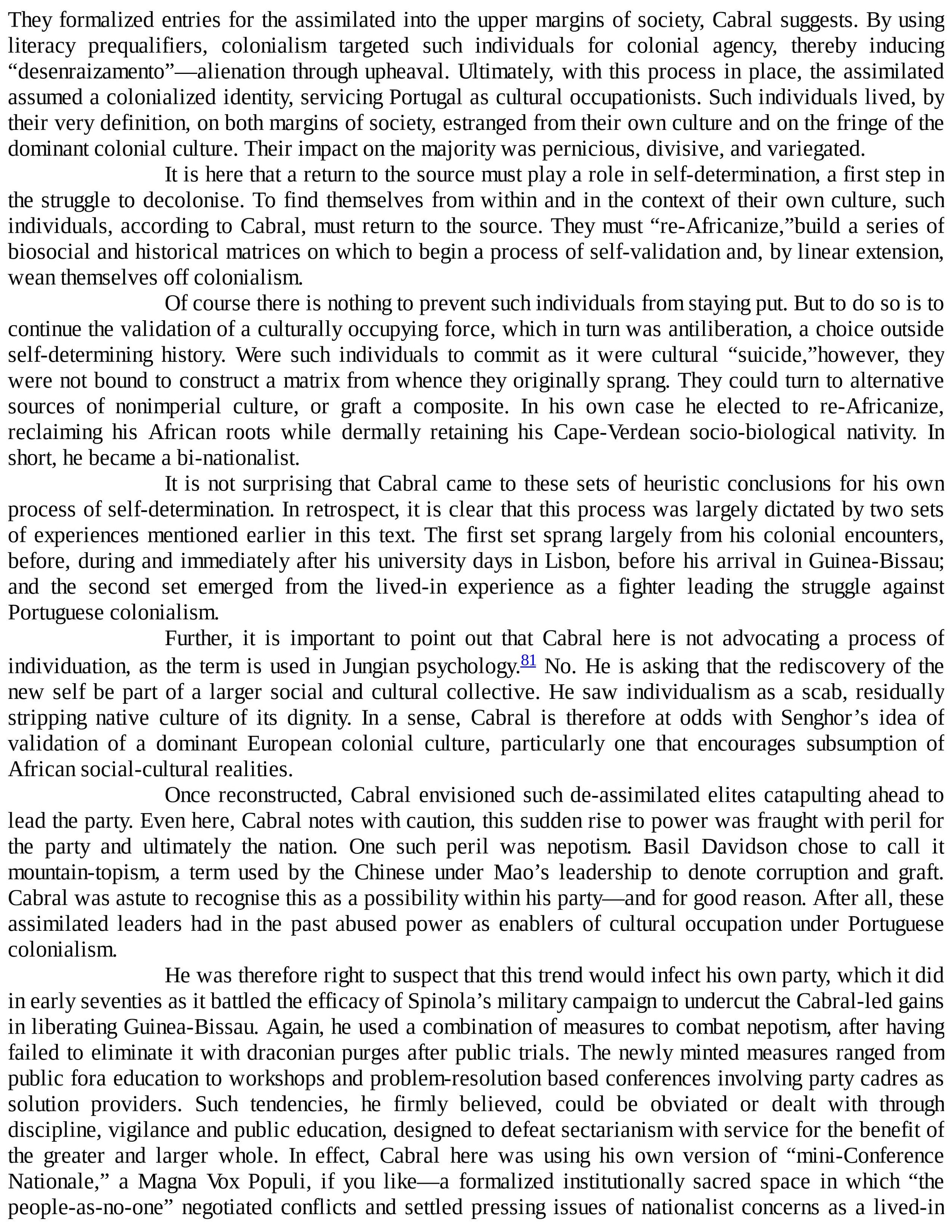

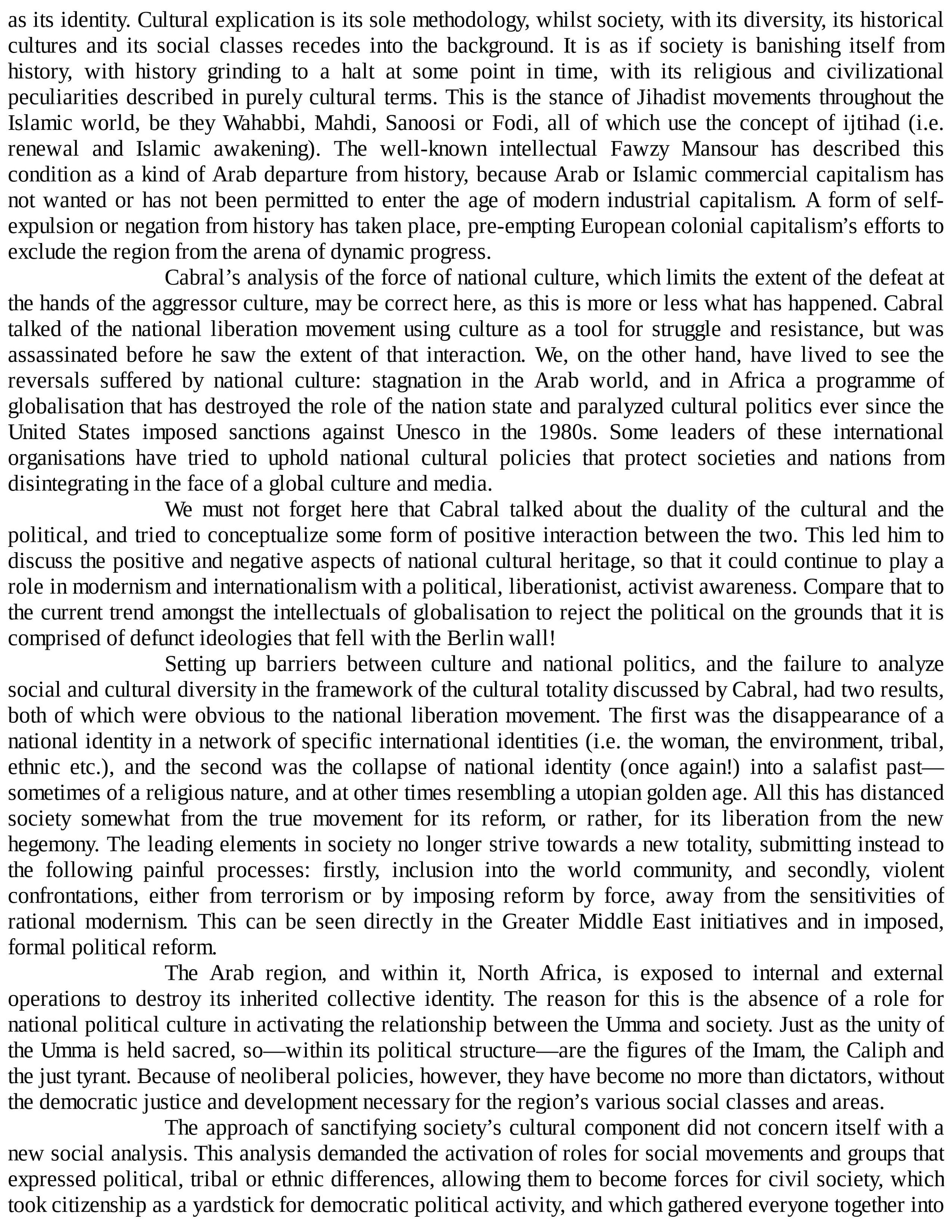

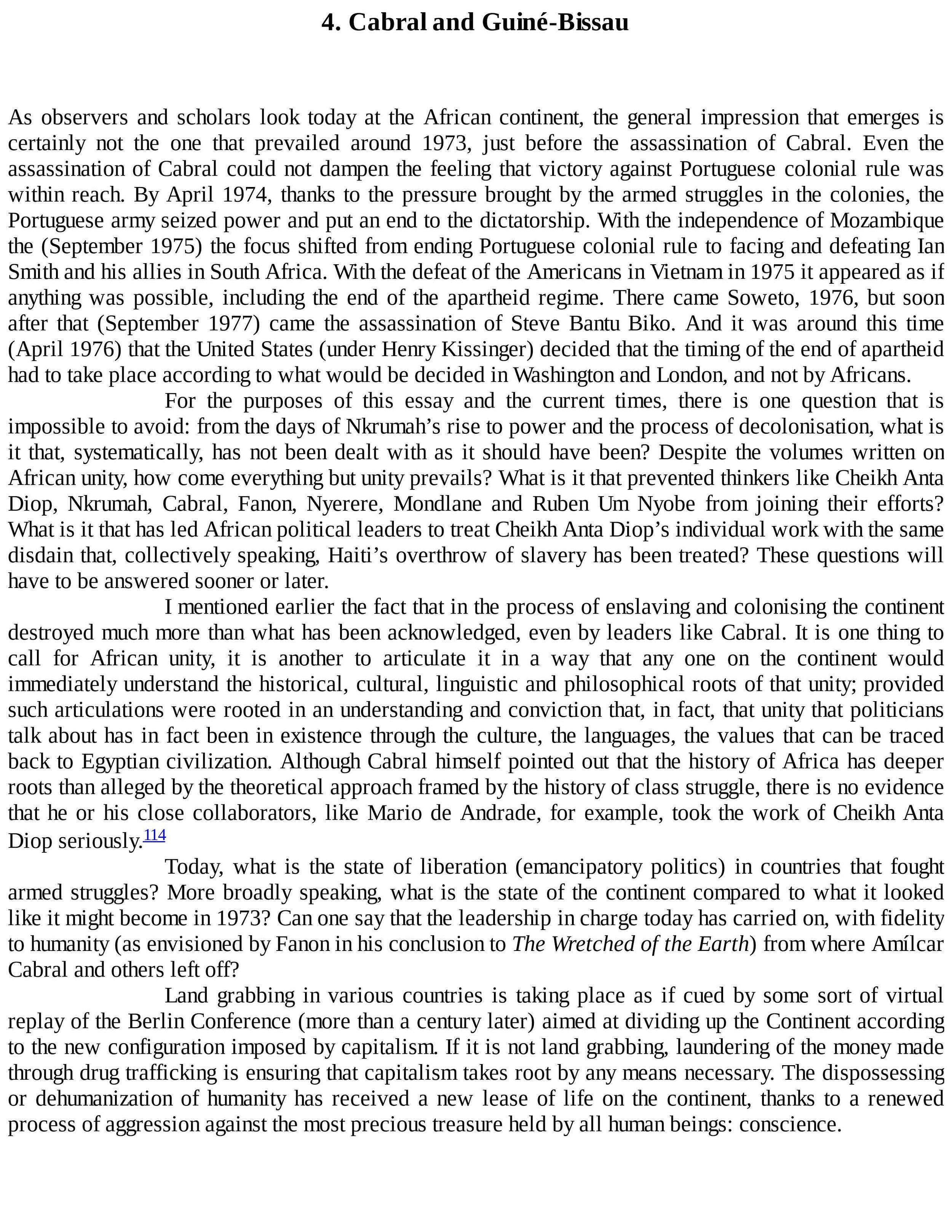

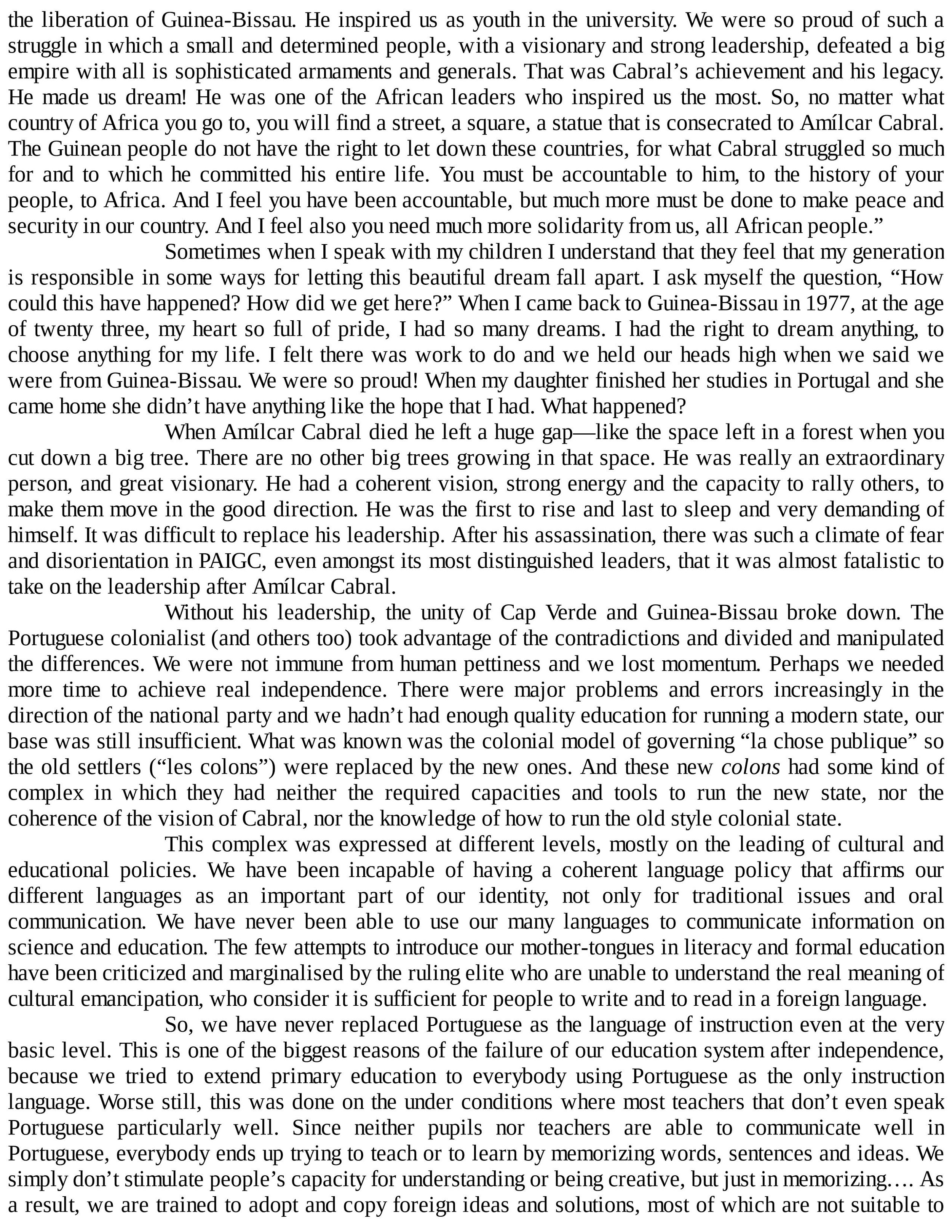

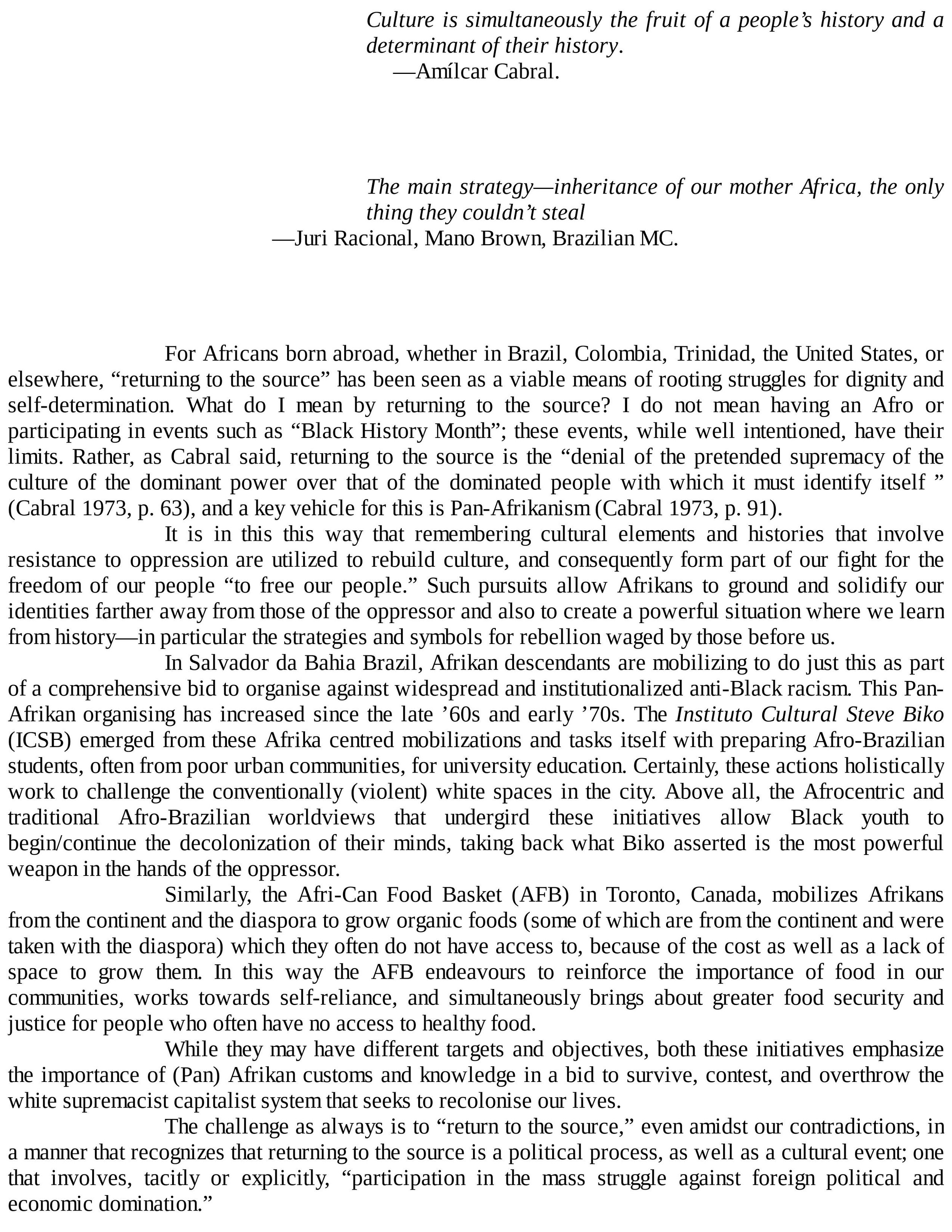

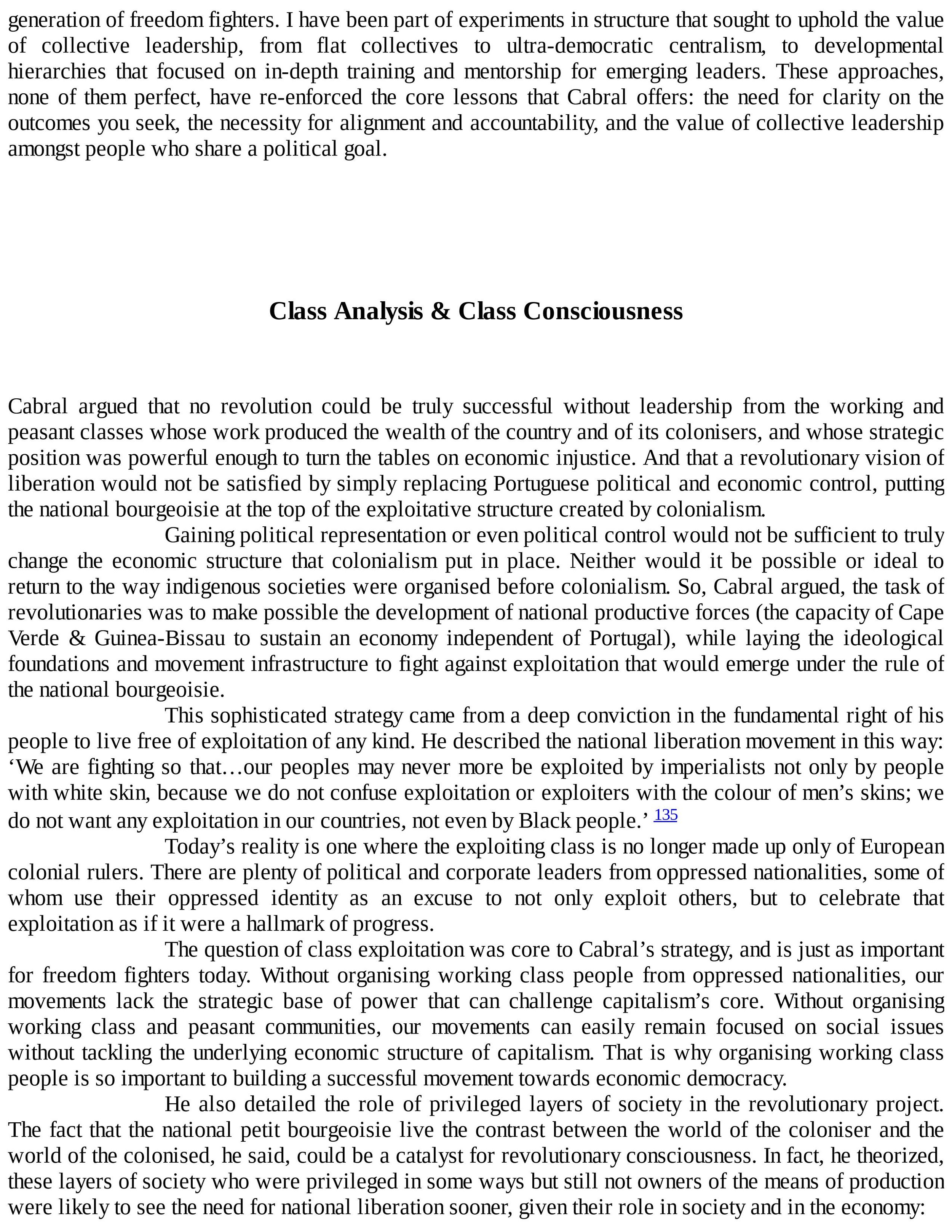

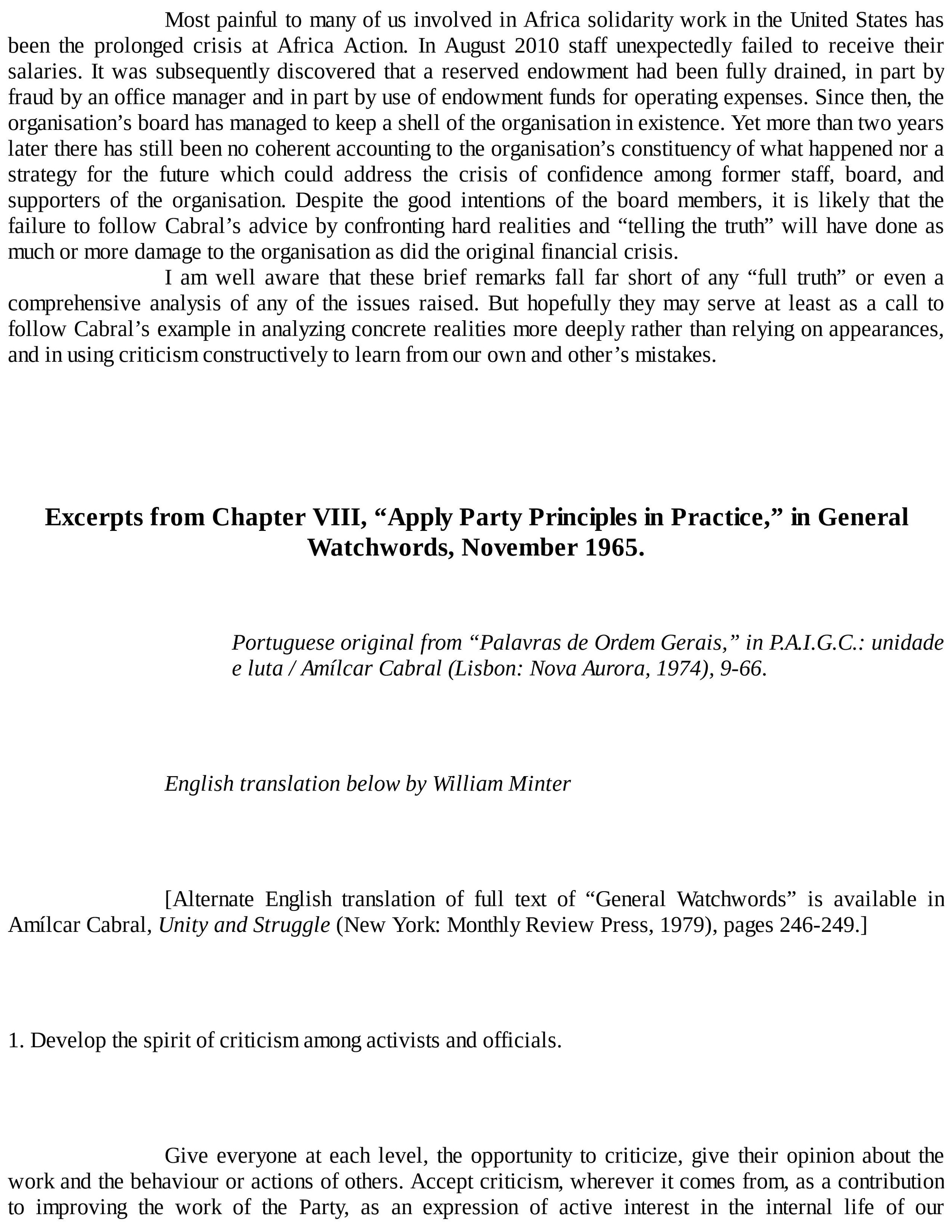

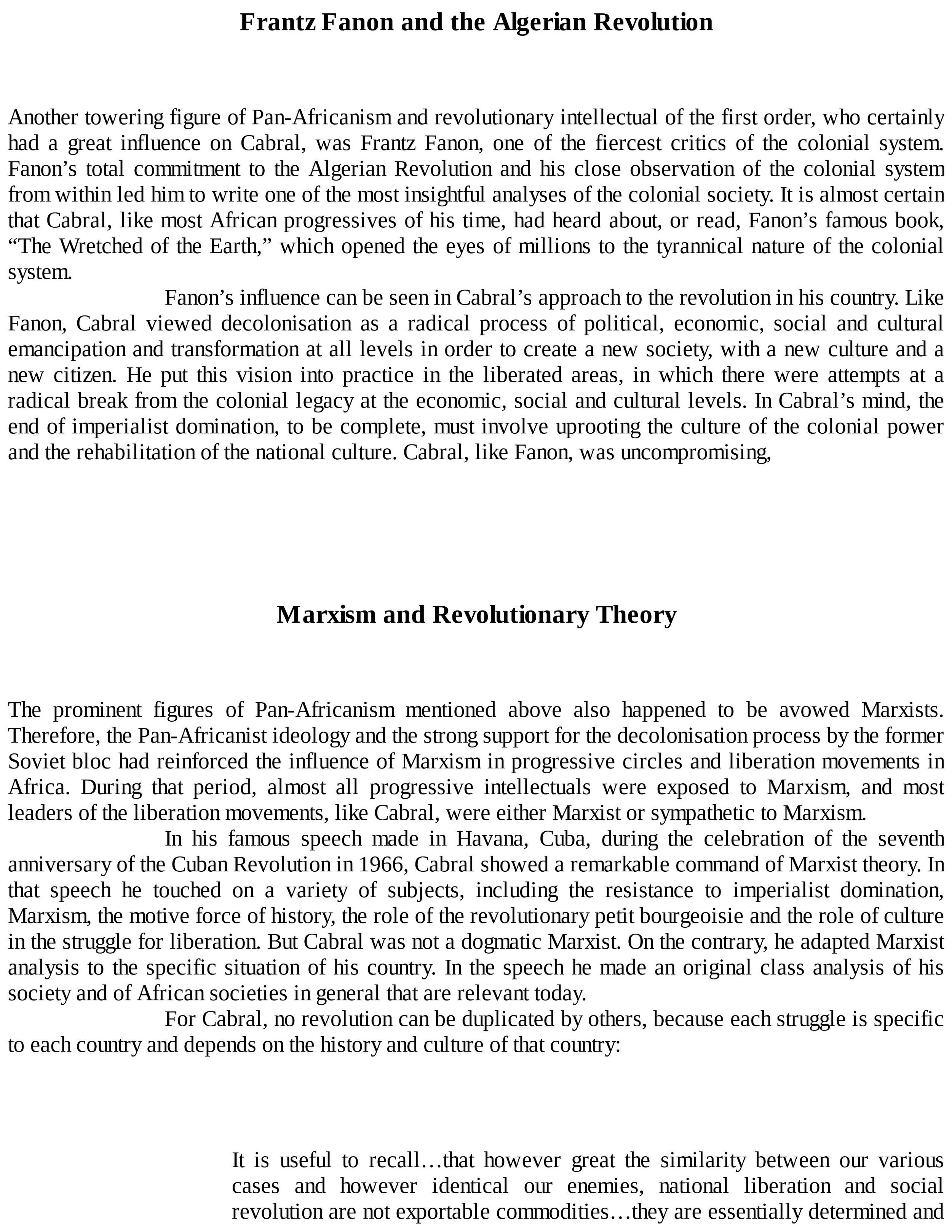

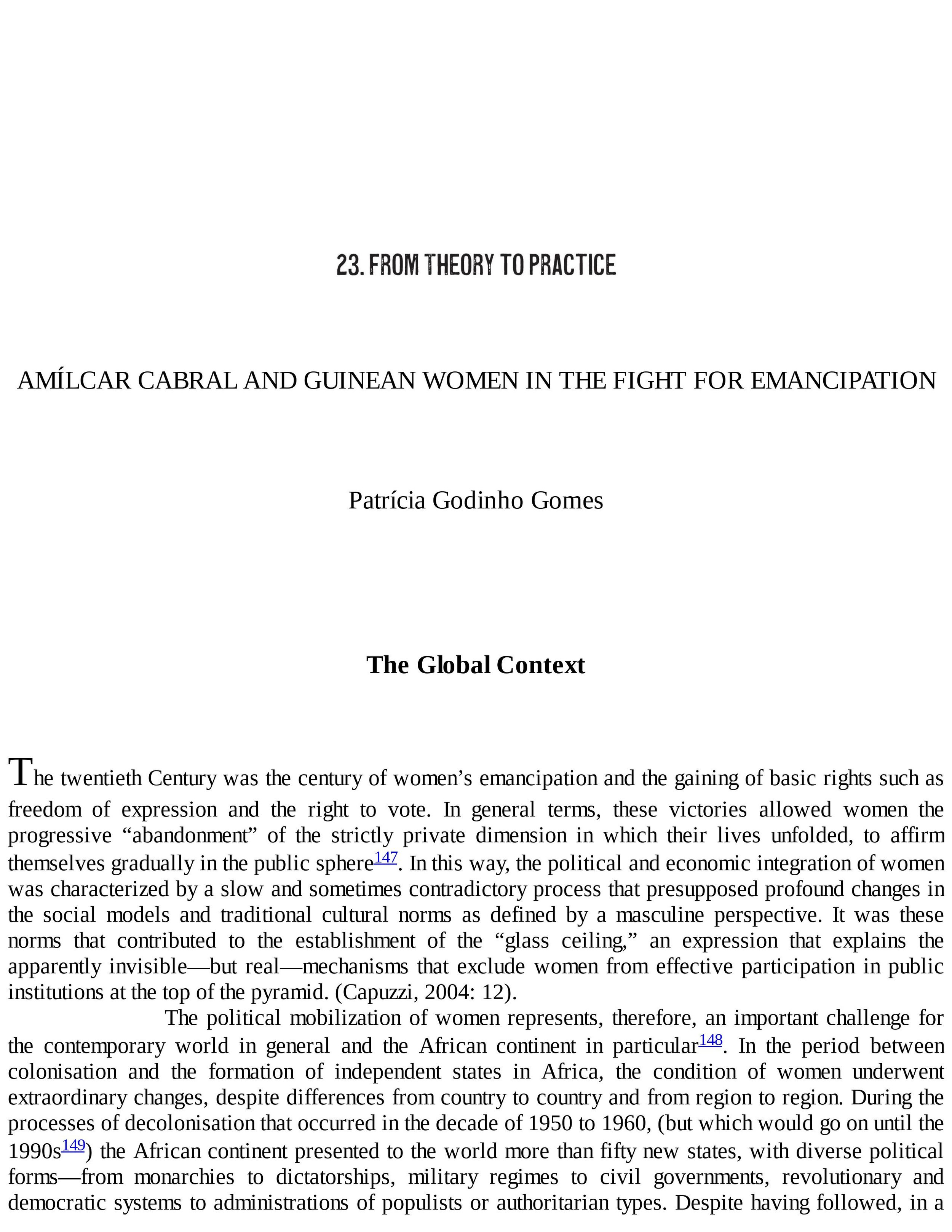

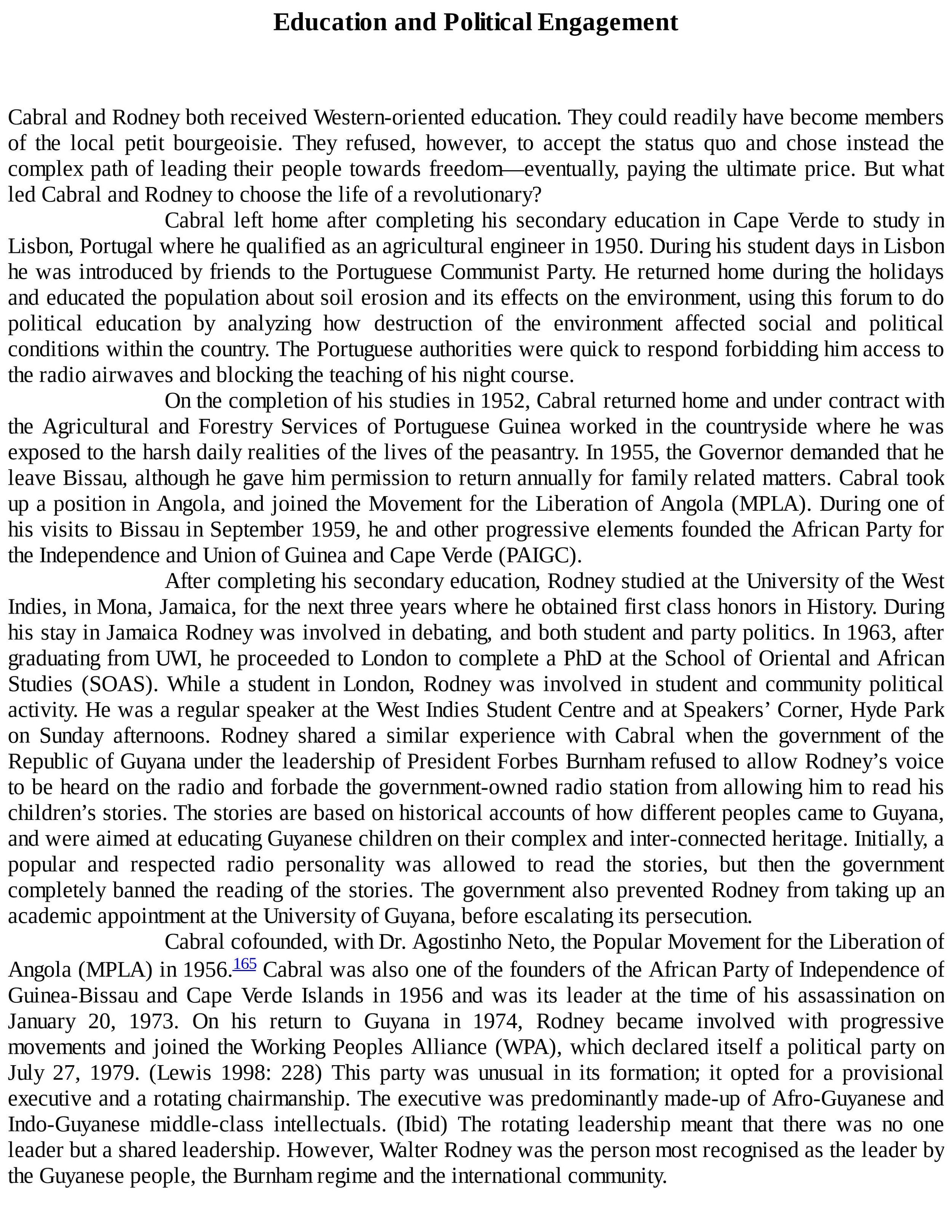

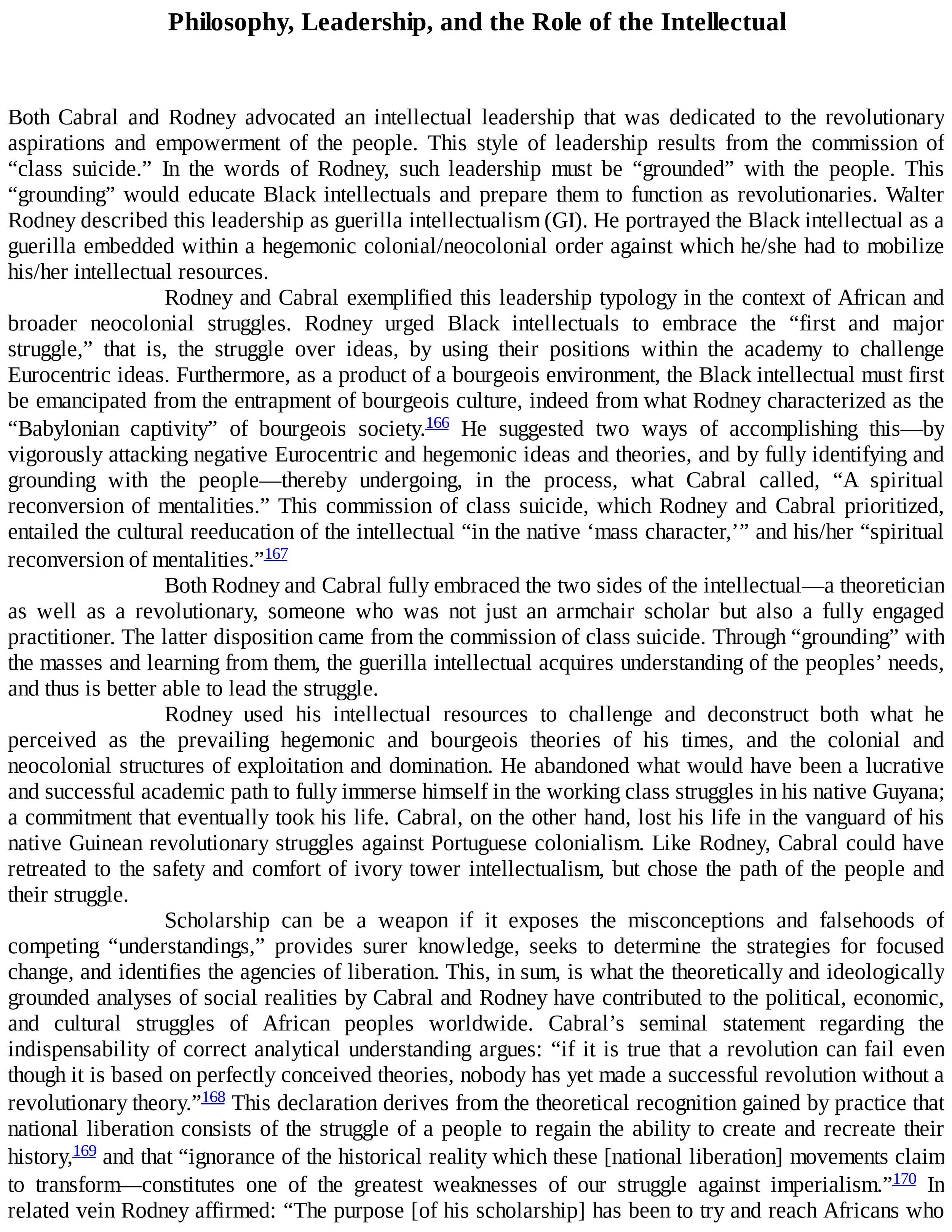

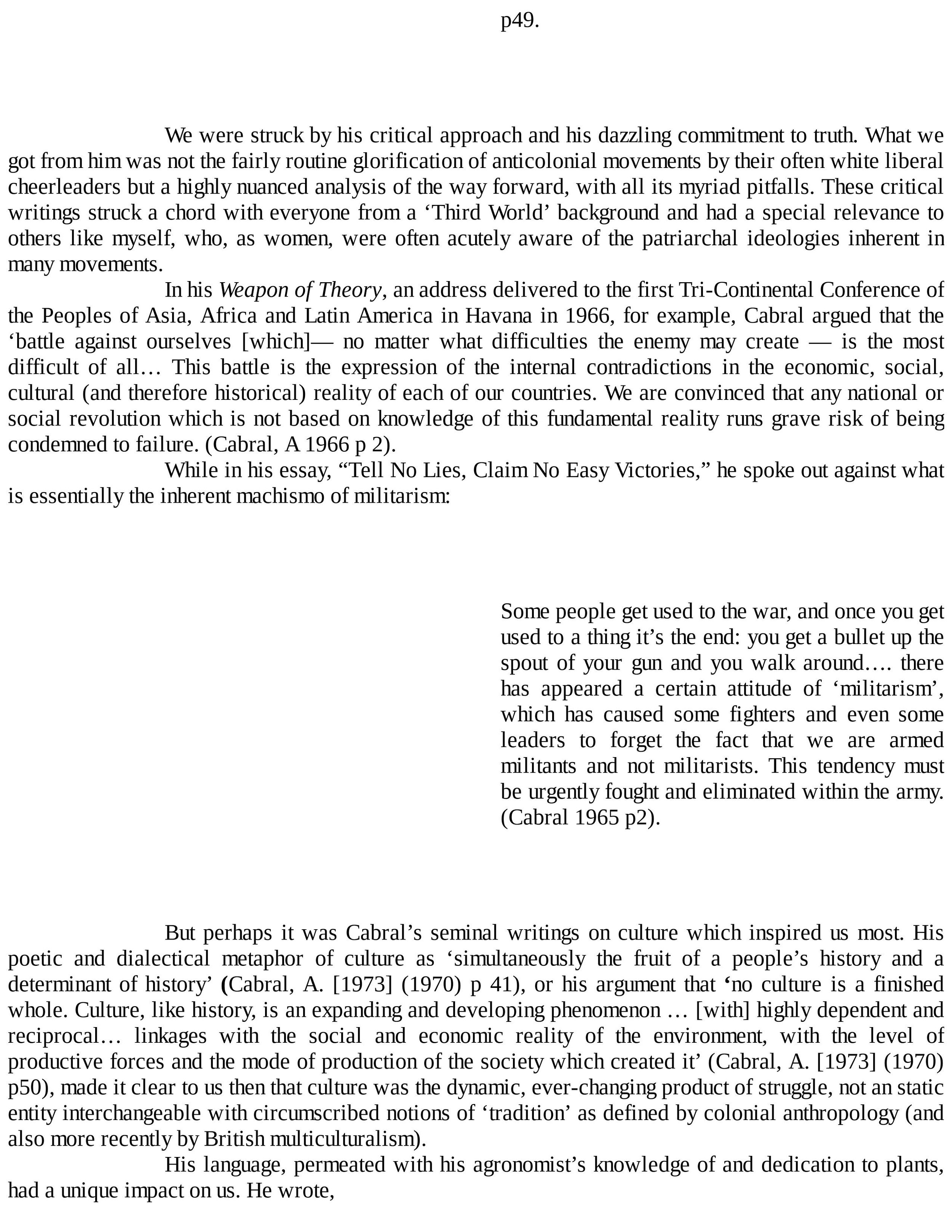

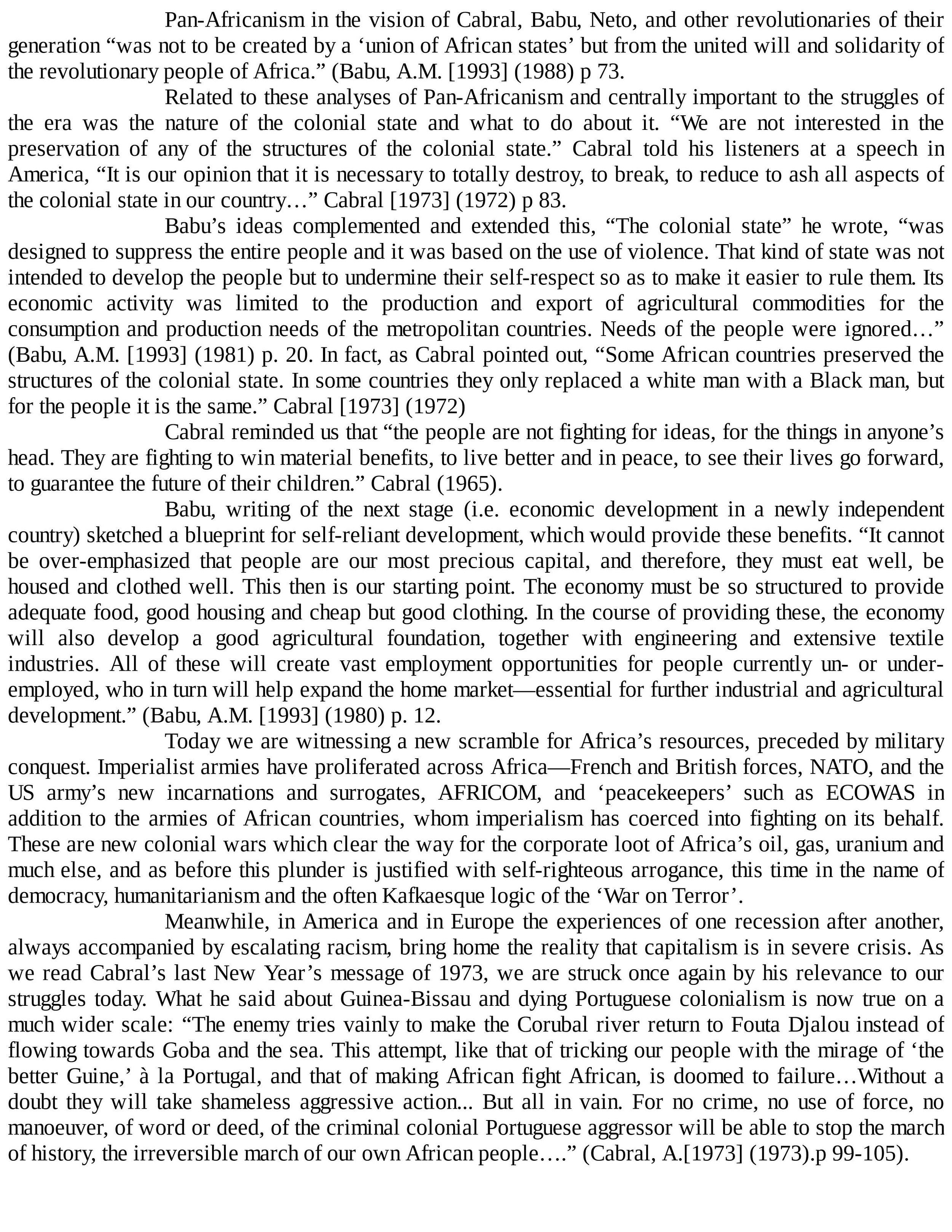

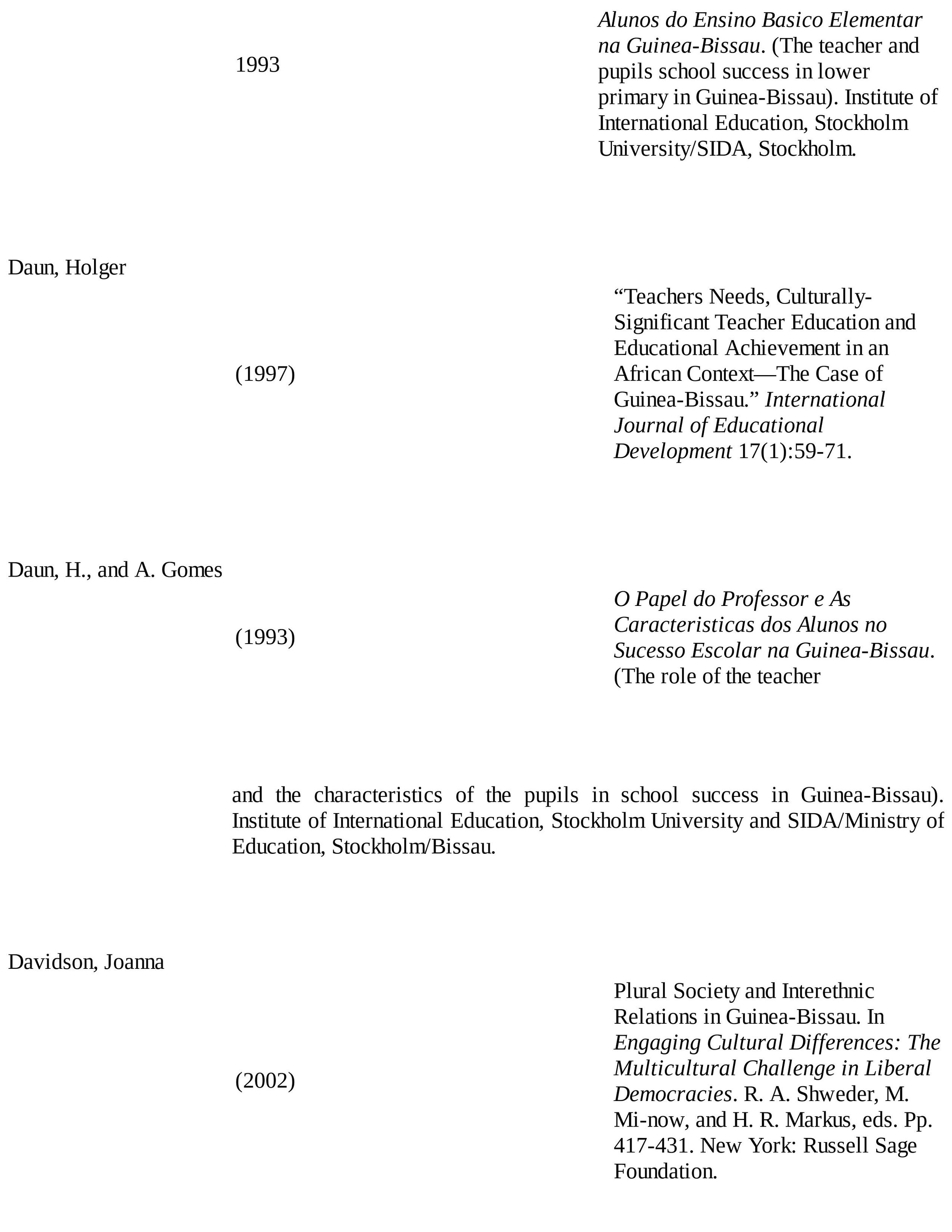

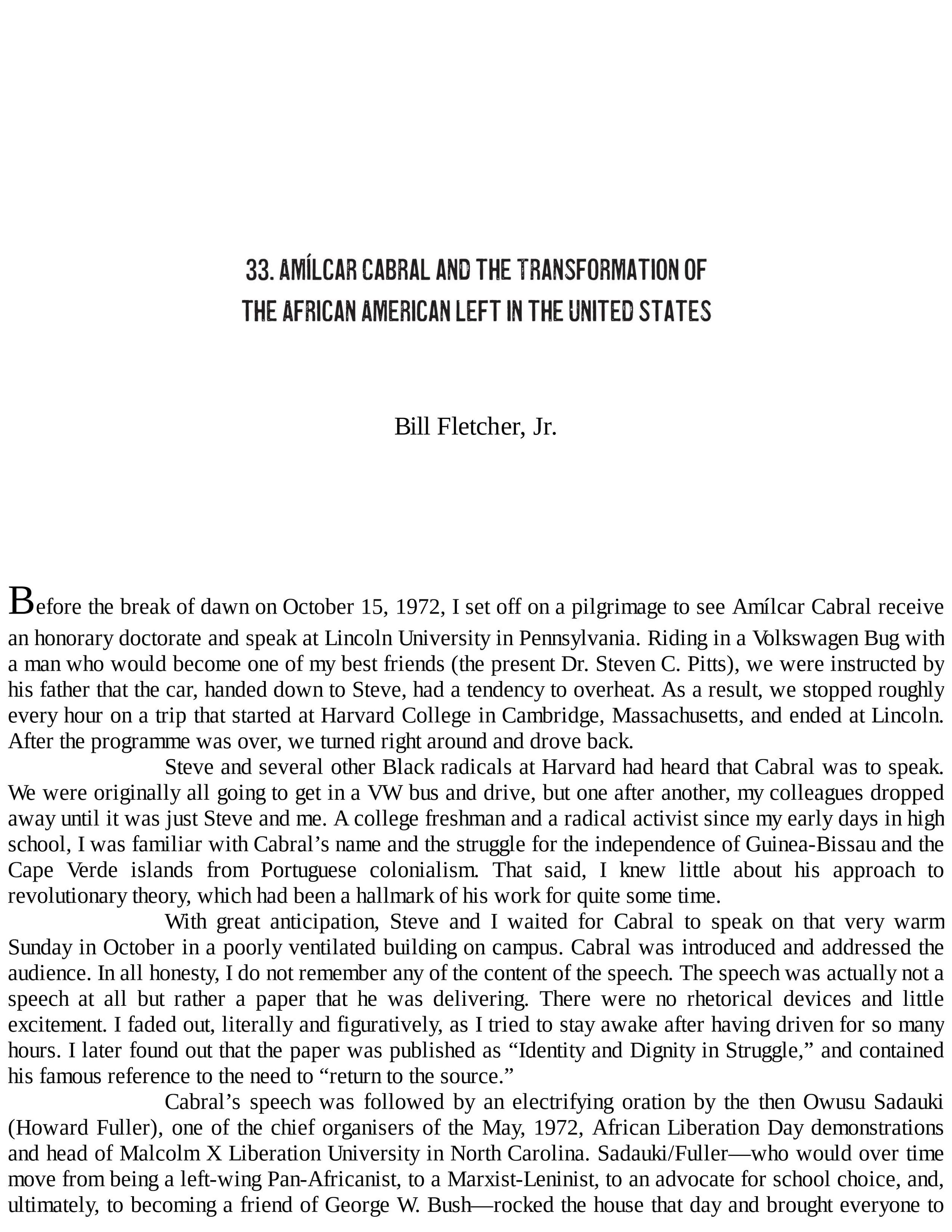

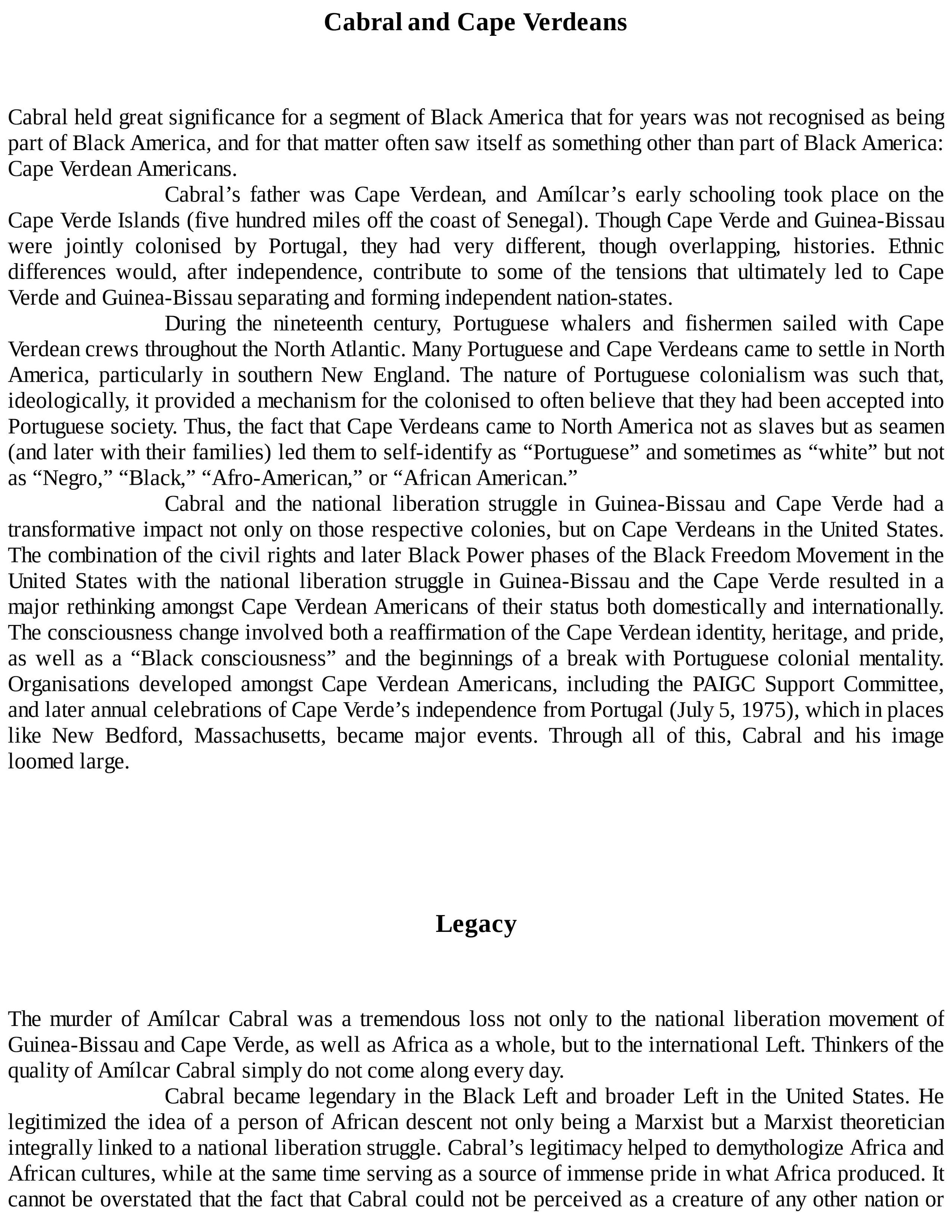

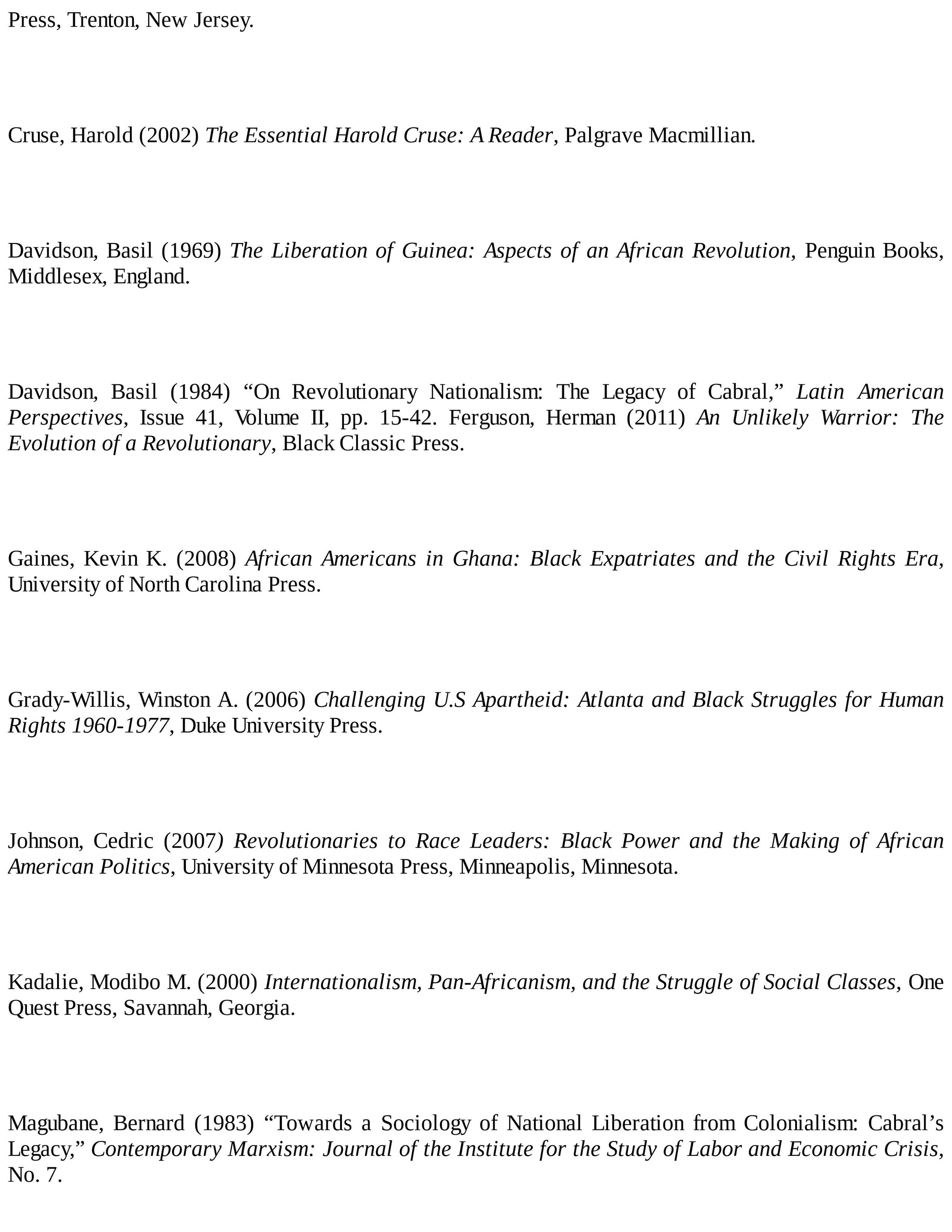

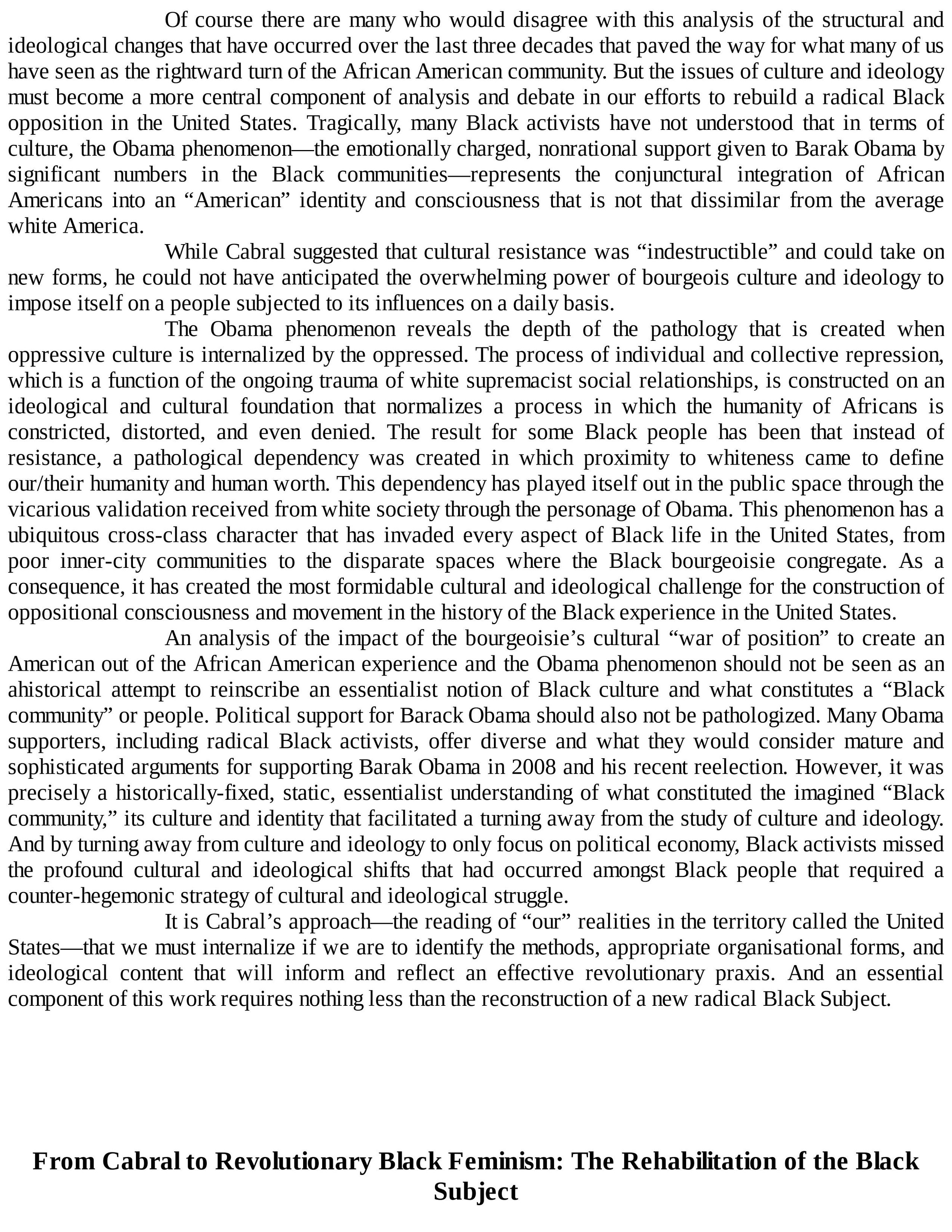

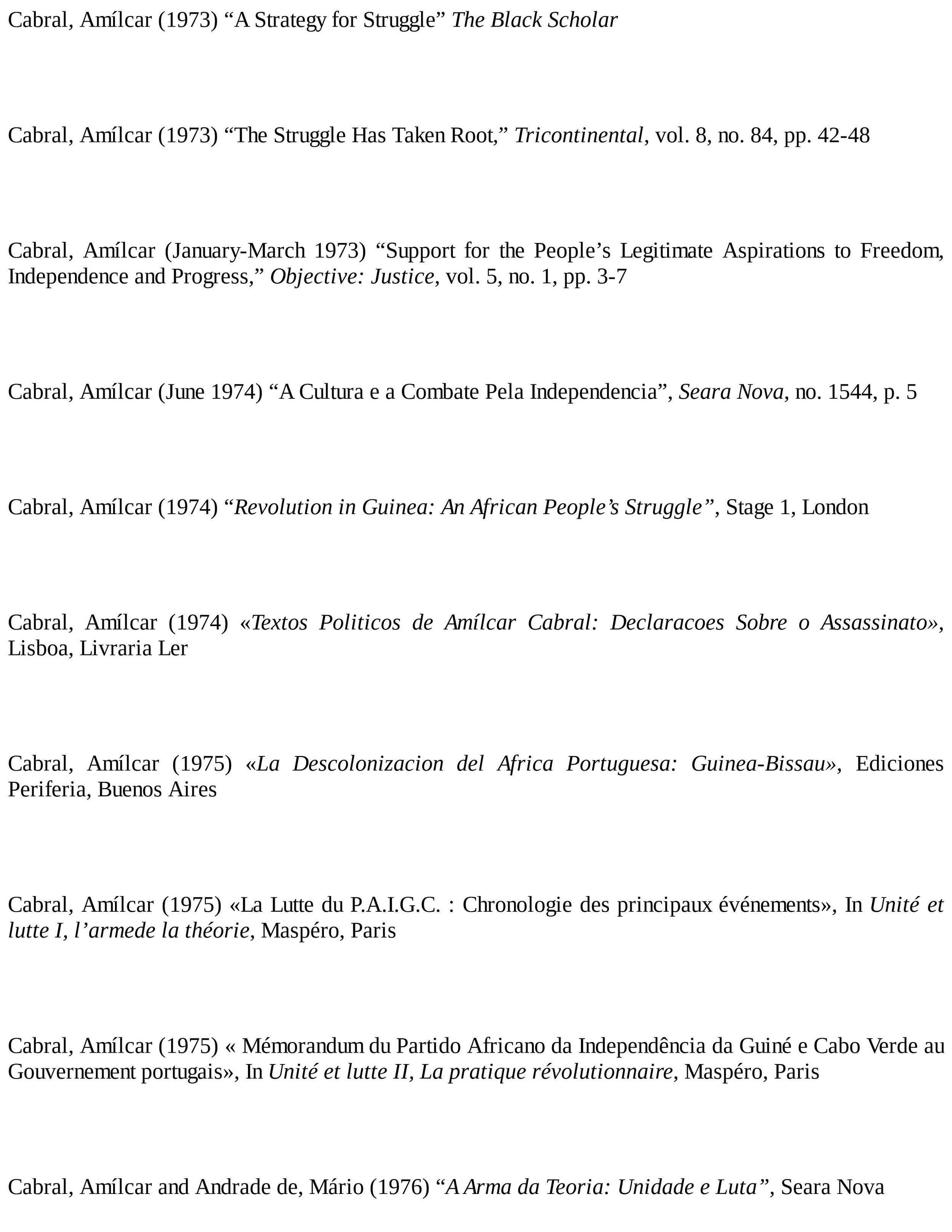

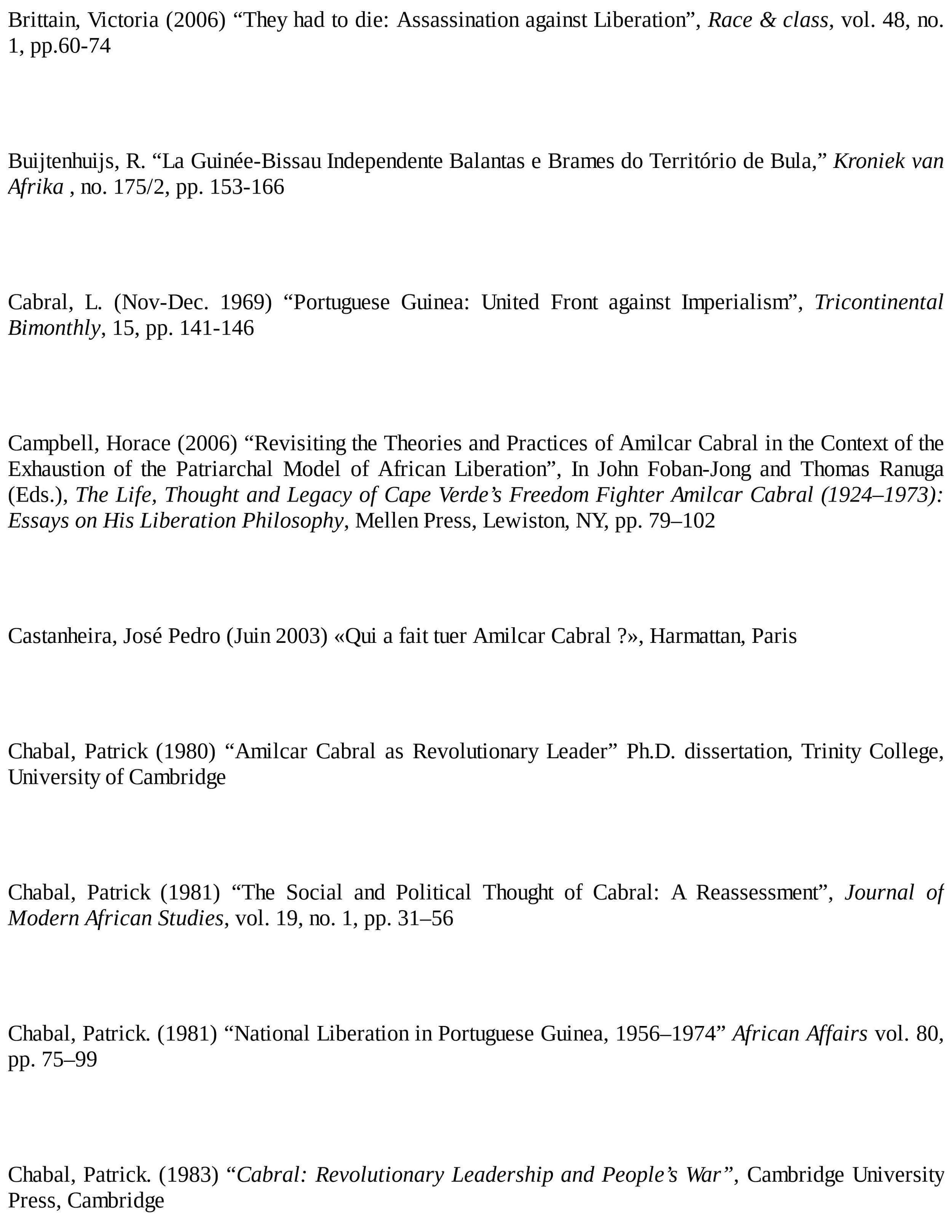

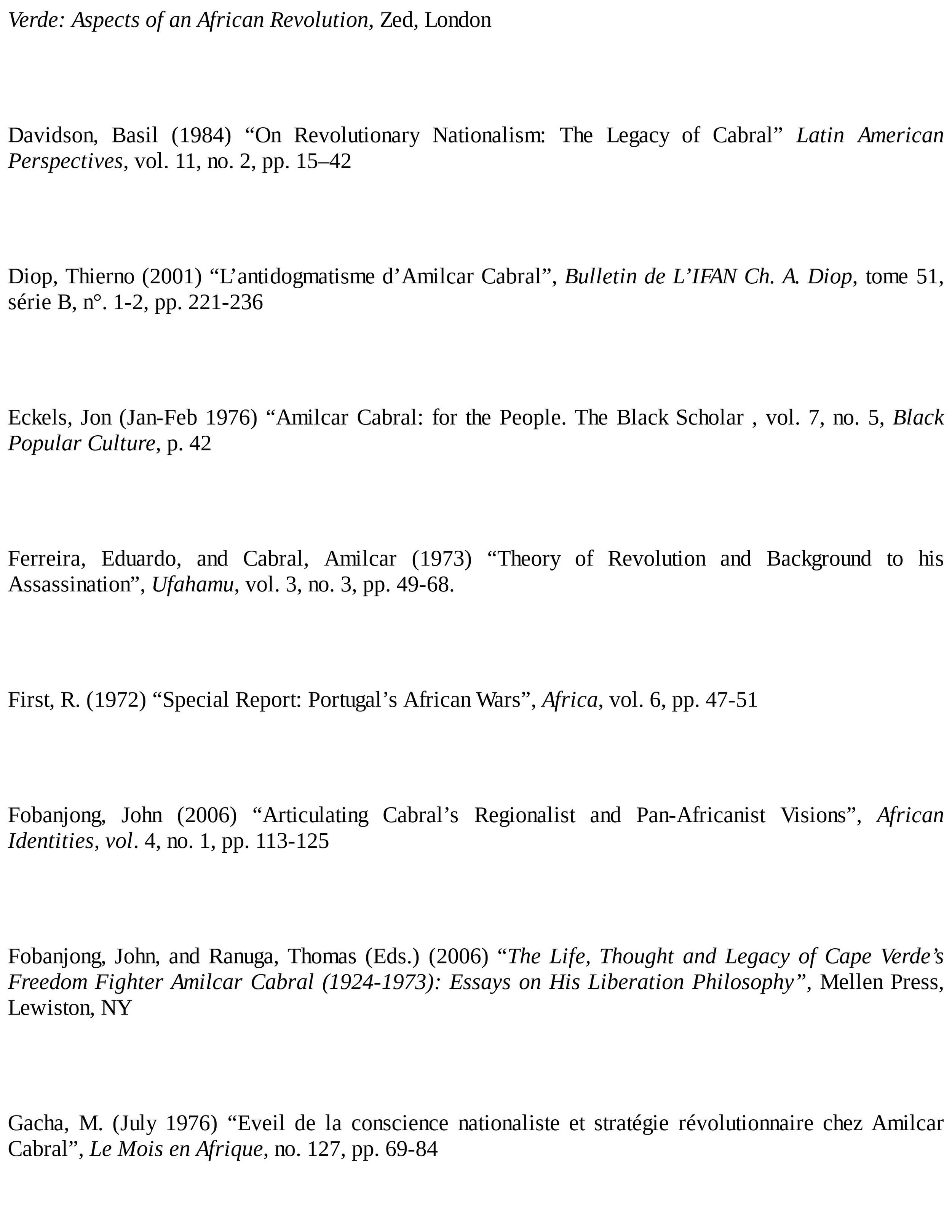

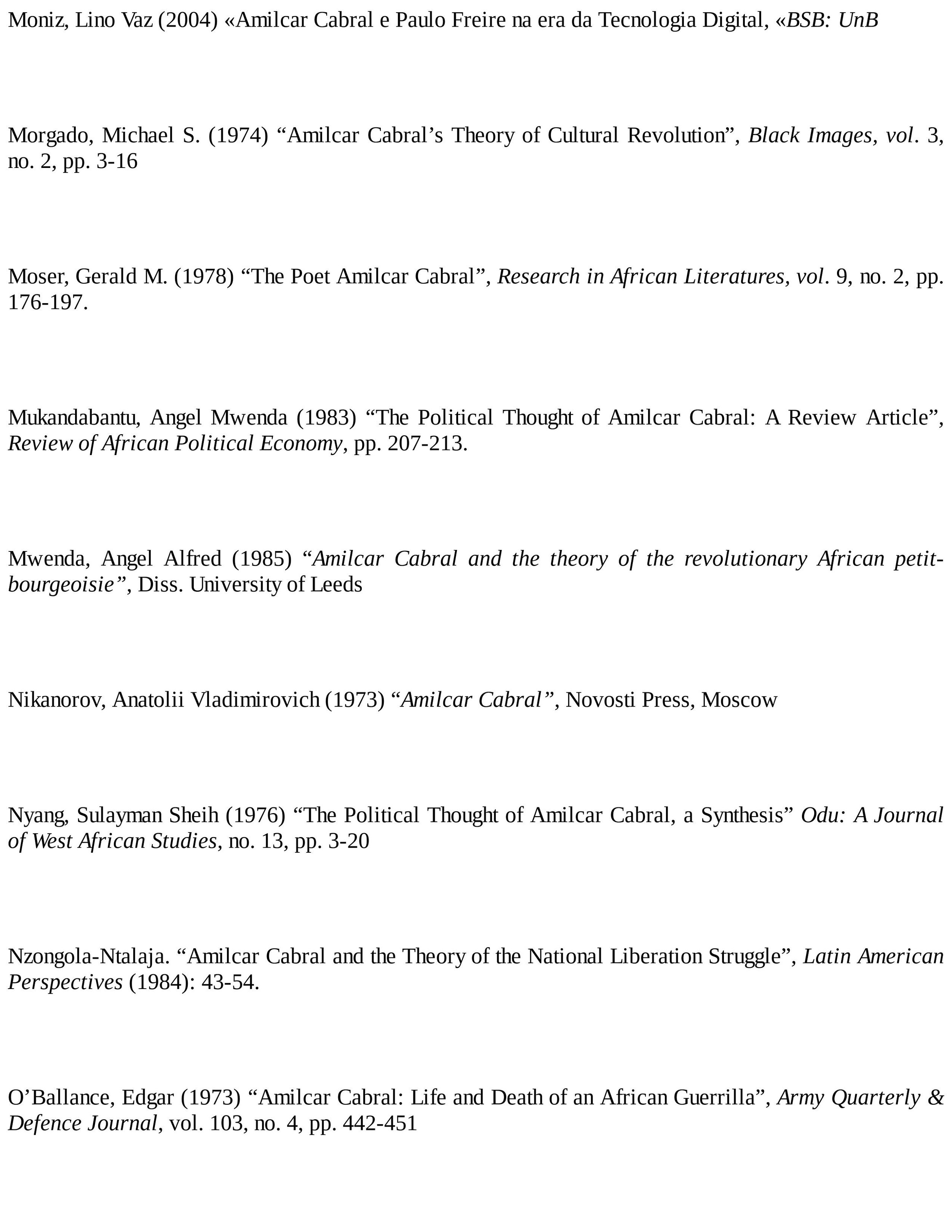

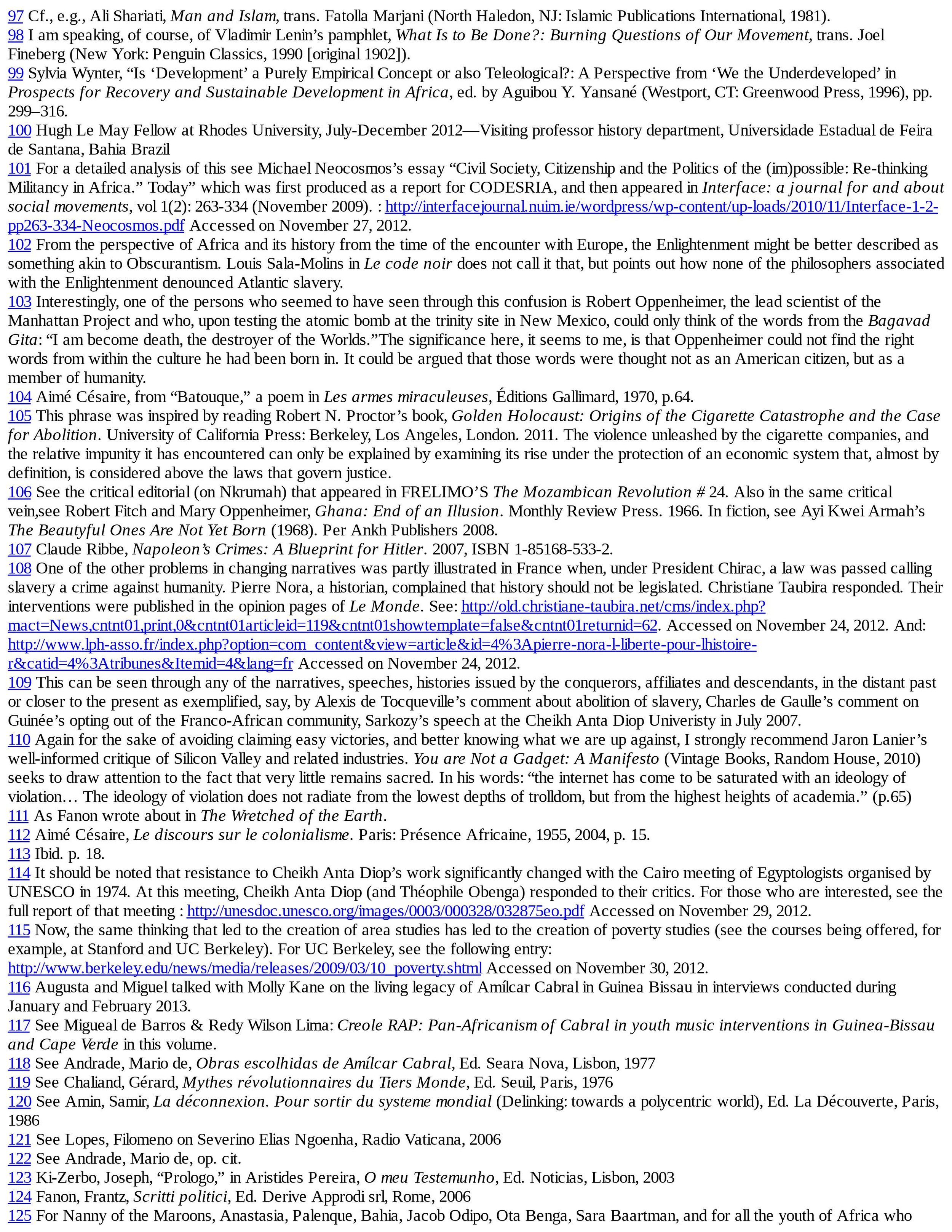

On October 15, 1972, Amilcar Cabral addressed an audience at Lincoln University where he received the honorary doctorate degree. The address was entitled, Return to the Source (see below).

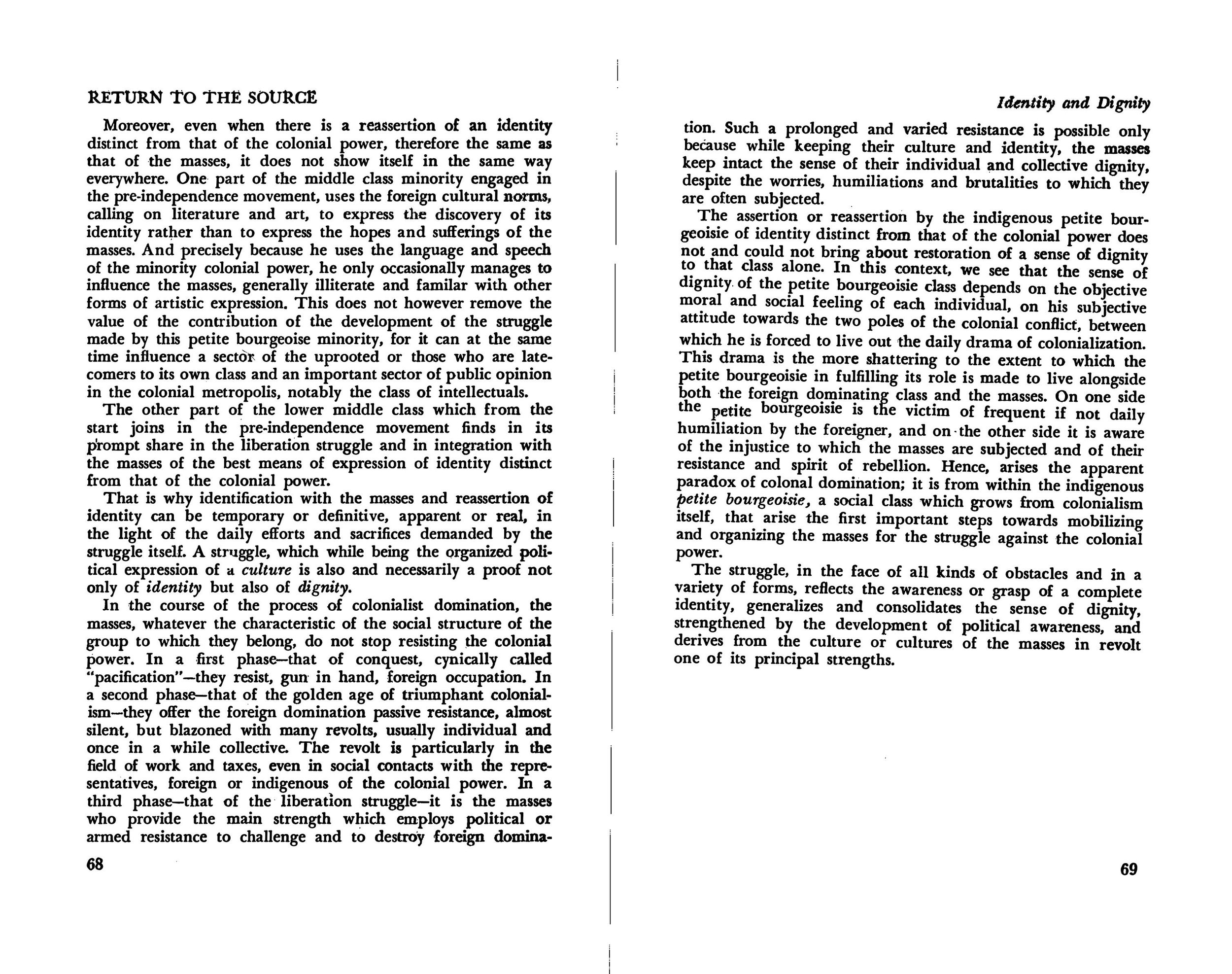

Amilcar Cabral addressing an audience at Lincoln University where he received the honorary doctorate during his last visit to the United States in October 1972. (AIS/Ray Lewis)

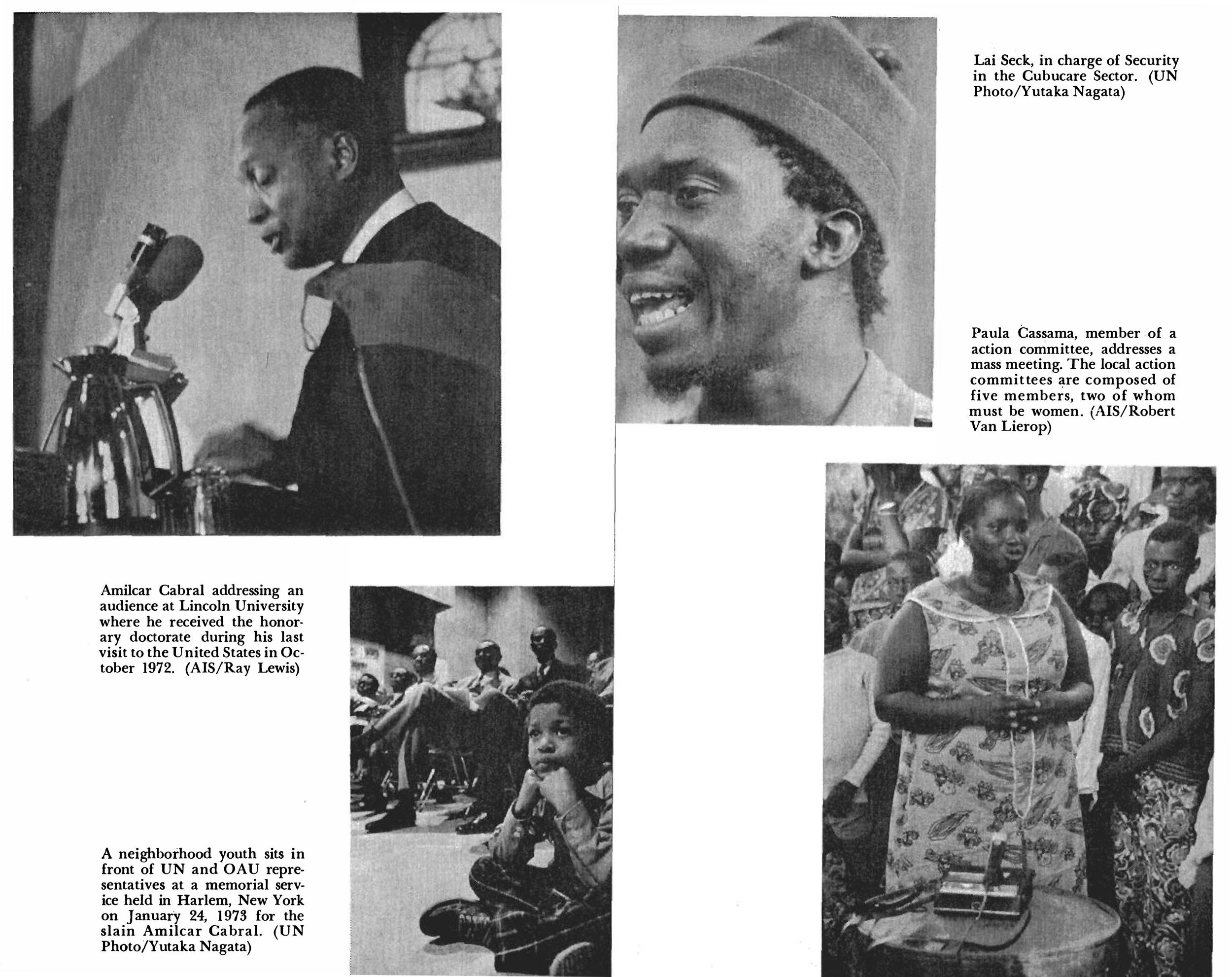

Amilcar Cabral then asked the Africa Information Service (AIS) to organise a small informal meeting at which he could speak with different black organisations. The AIS contacted approximately 30 organisations and on 20 October 1972, more than 120 people representing a wide range of black groups in America crowded into a small room to meet with Amilcar Cabral. At the meeting, the vitality, warmth and humour of Cabral the person became evident to those who had not met him before.

“At the period when the great exploitation of African men as slaves in the world appeared. . . . they decided to turn the archpelago into a storehouse for slaves. Folk taken from Africa, namely from Guine, were placed. . . as slaves. . . .There was constant resistance to this force. If the colonial force was acting in one direction, there was always our force which acted in the opposite direction.”

- Amilcar Cabral, Part 1: The Weapon of Theory - Party Principles and Political Practice: 4. Unity and struggle

Amilcar Cabral also said,

“FOR THE AFRICANS WHO FOR FIVE CENTURIES HAVE LIVED UNDER PORTUGUESE DOMINATION, PORTUGUESE COLONIALISM REPRESENTS A REIGN OF EVIL, AND WHERE EVIL REIGNS THERE IS NO PLACE FOR GOOD.” [ PART 1: THE WEAPON OF THEORY, PORTUGUESE COLONIAL DOMINATION]

“I am bringing to you - our African brothers and sisters of the United States - the fraternal salutations of our people in assuring you we are very conscious that all in this life concerning you also concerns us. If we do not always pronounce words that clearly show this, it doesn’t mean that we are not conscious of it. It is a reality and considering that the world is being made smaller each day all people are becoming conscious of this fact.

Naturally if you ask me between brothers (and sisters) and comrades what I prefer then if we are brothers it is not our fault or our responsibility. But if we are comrades, it is a political engagement. Naturally, we like our brothers (and sisters) but in our conception it is better to be a brother (or sister) and a comrade. We like our brothers very much, but we think that if we are brothers we have to realise the responsibility of this fact and take clear positions about our problems in order to see if beyond this condition of brothers and sisters, we are also comrades. This is very important for us.

We try to understand your situation in this country. You can be sure that we realise the difficulties you face, the problems you have and your feelings, your revolts, and also your hopes. We think that our fighting for Africa against colonialism and imperialism is a proof of understanding of your problem and also a contribution for the solution of your problems in the continent. Naturally the inverse is also true. All the achievements towards the solution of your problems here are real contributions to our own struggle. And we are very encouraged in our struggle by the fact that each day more of the African people born in America became conscious of their responsibilities to the struggle in Africa.

Does that mean you have to all leave here and go fight in Africa? We do not believe so. That is not being realistic in our opinion. History is a very strong chain. We have to accept the limits of history but not the limits imposed by the societies where we are living. There is a difference. We think that all you can do here to develop your own conditions in the sense of progress, in the sense of history and in the sense of our total realisation of your aspirations as human beings is a contribution for us. It is also a contribution for you to never forget that you are Africans.

Does that mean we are racists? No! We are not racists. We are fundamentally and deeply against any kind of racism. Even when people are subjected to racism we are against racism from those who have been oppressed by it. In our opinion - not from dreaming but from a deep analysis of the real condition of the existence of mankind and the division of societies - racism is a result of certain circumstances. It is not eternal in any latitude in the world. It is not the result of historical and economic conditions. And we cannot answer racism with racism. It is not possible. In our country, despite some racist manifestations by the Portuguese, we are not fighting against the Portuguese people or whites. We are fighting for the freedom of our people - to free our people and to allow them to be able to love any kind of human being. You cannot love when you are a slave. It is very difficult.

In combating racism we don’t make progress if we combat the people themselves. We have to combat the causes of racism. If a bandit comes into my house and I have a gun I cannot shoot the shadow of this bandit. I have to shoot the bandit. Many people lose energy and effort, and make sacrifices combating shadows. We have to combat the material reality that produces the shadow. If we cannot change the light that is one cause of the shadow, we can at least change the body. It is important to avoid confusion between the shadow and the body that projects the shadow. We are encouraged by the fact that each day more of our people, here and in Africa, realise this reality. This reinforces our confidence in our final victory.

The fact that you follow our struggle and are interested in our achievements is good for us. We base our struggle on the concrete realities of our country. We appreciate the experiences and achievements of other peoples and we study them. But revolution or national liberation struggle is like a dress which must be fitted to each individual’s body. Naturally, there are certain general or universal laws, even scientific laws for any condition, but the liberation struggle has to be developed according to the specific conditions of each country. This is fundamental.

The specific conditions to be considered include economic, cultural, social, political and even geographic conditions. The guerrilla manuals once told us that without mountains you cannot make guerrilla war. But in my country there are no mountains, only the people. In the economic field we committed an error. We began training our people to commit sabotage on the railroads. When they returned from their training we remembered that there were no railroads in our country. The Portuguese built them in Mozambique and Angola but not in our country.

There are other conditions to consider as well. You must consider the type of society in which you are fighting. Is it divided along horizontal or vertical lines? Some people tell us our struggle is the same as that of the Vietnamese people. It is similar, but it is not the same. The Vietnamese are a people that hundreds of years ago fought against foreign invaders like a nation. We are now forging our nation in the struggle. This is a big difference. It is difficult to imagine what a difference that makes. Vietnam is also a society with clear social structures with classes well defined. There is no national bourgeoisie in our country. A miserable petit bourgeoisie yes, but not a national bourgeoisie. These differences are very important.

Once I discussed politics with Eldridge Cleaver. He is a clever man, very intelligent. We agreed on many things but we disagreed on one thing. He told me your condition is a colonial condition. In certain aspects it seems to be, but it is not really a colonial condition. The colonial condition demands certain factors. One important factor is the continuity of territories. There are others, which you can see when you analyse. Many times we are confronted with a phenomenon that seem to be the same, but political activity demands that we be able to distinguish them. That is not to say that the aims are not the same. And, that is not to say that even some of the means cannot be the same. However, we must deeply analyse each situation to avoid loss of time and energy doing things that we are not to do and forgetting things that we have to do.

In our country we have been fighting for nearly 10 years. If we consider the changes achieved in that time, principally in the relationship between men and women, it has been more than 100 years. If we were only shooting bullets and shells, yes, 10 years is too much. But we were not only doing this. We were forging a nation during these years. How long did it take the European nations to be formed - 10 centuries from the middle ages to the renaissance. (Here in the United States you are still forging a nation - it is not yet completed, in my opinion. Several things have contributed to the forming and changing of this country, such as the Vietnam war, though unfortunately at the expense of the Vietnamese people. But you know the details of change in this country more than myself.)

Ten years ago, we were Fula, Mandjak, Mandinka, Balante, Pepel, and others. Now we are a nation of Guineans. Tribal divisions were one reason the Portuguese thought it would not be possible for us to fight. During these ten years we were making more and more changes, so that today we can see there is a new man and new woman, born with our new nation and because of our fight. This is because of our ability to fight as a nation.

Naturally, we are not defending the armed fight. Maybe I deceive people, but I am not a great defender of the armed fight. I am myself very conscious of the sacrifices demanded by the armed fight. It is a violence against even our own people. But it is not our invention - it is not our cool decision; it is the requirement of history. This is not the first fight in our country, and it is not Cabral who invented the struggle. We are following the example of our grandfathers who fought against Portuguese domination 50 years ago. Today’s fight is a continuation of the fight to defend our dignity, our right to have an identity - our own identity.

If it were possible to solve this problem without the armed fight - why not?! But while the armed fight demands sacrifices, it also has advantages. Like everything else in the world, it has two faces - one positive and the other negative - the problem is in the balance. For us now, it (the armed fight) is a good thing in our opinion, and our condition is a good thing because this armed fight helped us to accelerate the revolution of our people, to create a new situation that will facilitate our progress.

In these 10 years we liberated about three-fourths of the country and we were effectively controlling two-thirds of our country. We have much work to do, but we have our state, we have a strong political organisation, a developing administration, and we have created many services - always while facing the bombs of the Portuguese. That is to say, bombs used by the Portuguese, but made in the United States. In the military field we realised good things during these 10 years. We have our national army and our local militias. We have been able to receive a number of visitors - journalists, filmmakers, scientists, teachers, writers, government representatives, and others. We also received a very good report about the situation in our country.

However, through the armed fight, we realised other things more important than the size of the liberated regions or the capacity of our fighters, such as the irreversible change in the attitudes of our men. We have more sacrifices to make and more attitudes to overcome, but our people are now accustomed to this, and know that for freedom we must pay a price. What can we consider better than freedom? It is not possible - nothing compares with freedom. During the visit of the special mission of UN to our country, one of the official observers, while on a long march, asked a small boy if he ever got tired. The boy answered, ‘I can’t get tired - this is my country. Only the Portuguese soldiers get tired’.

Now we can accelerate the progress of the liberation of the rest of our country. Each day, we get more and better workers. Now we need more ammunition in order to give greater impact to our attacks against Portuguese positions. Instead of attacking with 80 shells, we have to attack with 800, if not 2,000, and we are preparing to do this. The situation is now better in the urban centres. We are dominating the urban centres in spite of the Portuguese occupation. Links with our underground organisation in these centers are very good, and we have decided to develop our action inside these centres. We told this on the radio to the Portuguese. We told all the people because the Portuguese cannot stop us. We told them before they would be afraid, and they are. They are even afraid of their shadows.

Another very positive aspect of our struggle, is the political situation on the Cape Verde Islands. Some days ago, there were riots between our people and the police. This is a sign that great developments are coming within the framework of our Islands.

We have taken all measures demanded by the struggle, in the political as well as the military field. With the general election just completed in the liberated region, we are now creating our National Assembly. Naturally we are not doing a National Assembly like the Congress you have here (USA) or the British parliament. All these are very important steps in accelerating the end of the colonial war in my country and for its total liberation.

We have decided to formally proclaim our state, and hope that our brothers and sisters here (USA), our brothers and sisters in Africa, and our friends all over the world, will take the necessary position of support for our initiatives in the political field. In an armed fight like ours, all the political aspects have been stressed. They are stressed naturally when you approach the end. It is a dialectical process. In the beginning the fight is political only, it is then followed by the transformation into the armed stage. Step by step, the political aspect returns but at a different level, the level of solution.

I am not going to develop these things further, I think it is better if you ask questions. We are very happy to be with you, our brothers and sisters. I tell you frankly, although it might hurt my visit to the UN; each day I feel myself that if I did not have to do what I have to do in my country, maybe I would come here to join you.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

CABRAL: I am at your disposal for any kind of question; no secrets, or ceremonies or diplomacy with you.

QUESTION: I am from Mali. I don’t know how comfortable you will be with this question, but given the nature of the fight you have been leading, are you satisfied with the type of moral, political and military aid you have been receiving from other African countries?

CABRAL: First of all, let me say to my brother that I am comfortable with any kind of question - there is no problem. Second, when one is in a condition that he has to receive aid, he is never satisfied. The condition of people who are obliged by circumstances to ask for and receive aid, is to never be satisfied. If you are satisfied it is finished, you don’t need aid. Third, we have to also consider the situation of the people who are helping us. You know the political and economic circumstances conditioning the attitudes of the African countries. It’s true the past decade of the 1960s was a great achievement for Africa - the independence of Africa. But we are not of this tree of independence of Africa. We must take our independence with force and our position is to never ask for the aid we need. We let each people give us aid as they can, and we never accept conditions with aid. If you give us aid like this, we are satisfied. If you can give more, we are more satisfied.

I have said to African heads of state many times that the aid from Africa is very useful, but not sufficient. We believe that they could do better, and so do they. Last June in the Rabat summit meetings (of the OAU) they agreed to increase their aid by 50 per cent. Why didn’t they do this before? We know that they had not only financial and economic difficulties, but political difficulties as well. In some cases, the difficulty was a lack of consciousness about the importance of this problem. But each day they are realising more and maybe when they fully realise the importance of this problem we will all be independent.

QUESTION: I would like to know what forward thrust your country would have in the absence of NATO support, that this country gives, and what the arguments are that the US offers for its participation in NATO which we all know is the conduit which supplies the Portuguese with their arms? This is something that we can take immediate political action on.

CABRAL: You see, Portugal is an underdeveloped country - the most backward in Western Europe. It is a country that doesn’t produce even toy planes - this is not a joke, it’s true. Portugal would never be able to launch three colonial wars in Africa without the help of NATO, the weapons of NATO, the planes of NATO, the bombs of NATO - it would be impossible for them. This is not a matter for discussion. The Americans know it, the British know it, the French know it very well, the West Germans also know it, and the Portuguese know it very well.

We cannot talk of American participation in NATO, because NATO is the creation of the United States. Once I came here to the US and I was invited to lunch by the representative of the US on the United Nations’ Fourth Committee. He was also the deputy chief of the US delegation to the UN. I told him we are fighting against Portuguese colonialism, and not asking for the destruction of NATO. We don’t think it is necessary to destroy NATO in order to free our country. But why is the US opposing this? He told me that he did not agree with this policy (US support of NATO) but that there is a problem of world security and in the opinion of his government it is necessary to give aid to Portugal in exchange for use of the Azores as a military base. Acceptance of Portuguese policy is necessary for America’s global strategy, he explained.

I think he was telling me the truth, but only part of the truth because the US supports Portugal in order to continue the domination of Africa, if not over other parts of the world. I must clarify that this man left his position in the UN and during his debate in the US Congress took a clear position favourable to ours and asked many times for aid to Portugal to be stopped, but the government didn’t accept.

What is the justification for this? There is no justification - no justification at all. It is US imperialism. Portugal is an appendage of imperialism, a rotten appendage of imperialism. You know that Portugal is a semi-colony itself. Since 1775 Portugal has been a semi-colony of Britain. This is the only reason that Portugal was able to preserve the colonies during the partition of Africa. How could this poor miserable country preserve the colonies during the partition of Africa? How could this poor miserable country preserve the colonies in the face of the ambitions and jealousies of Germany, France, England, Belgium, and the emerging American imperialism? It was because England adopted a tactic. It said - Portugal is my colony, if it preserves colonies they are also my colonies - and England defended the interests of Portugal with force. But now it is not the same. Angola is not really a Portuguese colony. Mozambique is not really a Portuguese colony. You can see the statistics. More than 60 per cent of the principal exports of Angola are not for Portugal. Approximately the same percentage of the investments in Angola and Mozambique are not Portuguese, and each day this is increasing. Guinea and Cape Verde are very poor and do not have very good climates. They are the only Portuguese colonies. Portugal is, principally for Angola and Mozambique, the policeman and the receiver of taxes. But they will not tell you this.

QUESTION: My question concerns the basis of law you are using in your country. Are you using the laws of the Portuguese in terms of the National Assembly? What kinds of criteria are you going to use?

CABRAL: If Portugal had created in my country an Assembly, we would not create one ourselves. We don’t accept any institution of the Portuguese colonialists. We are not interested in the preservation of any of the structures of the colonial state. It is our opinion that it is necessary to totally destroy, to break, to reduce to ash all aspects of the colonial state in our country in order to make everything possible for our people. The masses realise that this is true, in order to convince everyone we are really finished with colonial domination in our country.

Some independent African states preserved the structures of the colonial state. In some countries they only replaced a white man with a black man, but for the people it is the same. You have to realise that it is very difficult for the people to make a distinction between one Portuguese, or white, administrator and one black administrator. For the people it is the administrator that is fundamental. And the principle - if this administrator, a black one is living in the same house, with the same gestures, with the same car, or sometimes a better one, what is the difference? The nature of the state we want to create in our country is a very good question for it is a fundamental one.

Our fortune is that we are creating the state through the struggle. We now have popular tribunals - people’s courts - in our country. We cannot create a judicial system like the Portuguese in our country because it was a colonial one, nor can we make a copy of the judicial system in Portugal - it is impossible. Through our struggle we created our courts and the peasants participate by electing the courts themselves. Ours is a new judicial system, totally different from any other system, born in our country through the struggle. It is similar to other systems, like the one in Vietnam, but it is also different because it corresponds to the conditions of our country.

If you really want to know the feelings of our people on this matter I can tell you that our government and all its institutions have to take another nature. For example, we must not use the houses occupied by the colonial power in the way they used them. I proposed to our party that the government palace in Bissau be transformed into a people’s house for culture, not for our prime minister or something like this (I don’t believe we will have prime ministers anyway). This is to let the people realise that they conquered colonialism - it’s finished this time - it’s only a question of a change of skin. This is really very important. It is the most important problem in the liberation movement. The problem of the nature of the state created after independence is perhaps the secret of the failure of African independence.

QUESTION: Looking at Africa geographically, where does the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde Islands (PAIGC) get most of its support, North Africa, or Sub-Saharan Africa, and in a broader sense, how does support from Russia and China compare?

CABRAL: We don’t like this division of Africa. We have the support of the OAU for some years now. We have the total support of OAU. All African countries support PAIGC, no exceptions of any voice against us. And through the OAU, the liberation committee gives us financial help. There are some African countries, maybe not more than the fingers on the hand, that help us directly also. With them we have bilateral relations. Some are in the north, others in the west, and others in the east.

About China and the Soviet Union, we always had the support of the socialist countries - moral, political and material. Some have given more material support than others. Until now the country that has helped us most is the Soviet Union, and we have said it many times before at all kinds of meetings. Until now they’ve helped us the most in supplying materials for the war. If you want to verify this you can come to my country and see. This is the situation.

QUESTION: My question is about the role of women. What is the nature of the transformation from the old system under imperialism?

CABRAL: In our country you find many societies with different traditions and rules on the role of women. For example, in the Fula society a woman is like a piece of property of the man, the owner of the home. This is a typical patriarchal society. But even there women have dignity, and if you enter the house you would see that inside the house, the woman is the chief. On the other hand, in Balante society women have more freedom.

To understand these differences you have to know that in Fula society all that is produced belongs to the father. In Balante society all that is produced belongs to the people that work and women work very hard so they are free. It is very simple. But the problem is about the political role in the fight. You know that in our country there were even matriarchal societies where women were the most important element. On the Bijagos Islands they had queens. They were not queens because they were the daughters of kings. They had queens succeeding queens. The religious leaders were women too. Now they are changing.

I tell you these things so that you can understand our society better. But during the fight the important thing is the political role of women. Yes, we have made great achievements, but not enough. We are very far from what we want to do, but this is not a problem that can be solved by Cabral signing a decree. It is all part of the process of transformation, of change in the material conditions of the existence of our people, but also in the minds of the women, because sometimes the greatest difficulty is not only in the men but in the women too.

We have a big problem with our nurses, because we trained about three hundred nurses – women – but they married, they get children and for them it’s finished. This is very bad. For some this doesn’t happen. Carmen Pereira, for instance, is a nurse, and she is a member of the high political staff of the party. She is responsible for all social and cultural problems in the southern liberated region. She’s a member of the executive committee of the party. There are many others too, trained not only in the country but in the exterior also, in foreign countries. But we have much work to do.

In the beginning of the struggle, when we launched the guerrilla struggle, young women came without being called and asked for weapons to fight, hundreds and hundreds. But step-by-step some problems came in this framework and we had to distribute, to partition the war. Today, women are principally in what you call the local armed forces and in the political war - working on health problems, and instruction also.

I hope we can send some of our women here so you will be able to know them. But we have big problems to solve and we have a great problem with some of the leaders of the party. We have (even myself) to combat ourselves on this problem, because we have to be able to cut this cultural element, with its great roots, until the day we put down this bad thing - the exploitation of women, but we have made great progress in this field in these 10 years.

QUESTION: Comrade Cabral, you spoke about universal scientific laws of revolution. It is very clear that in this country, we too, are engaged in some stage of development of a revolutionary struggle. Certainly, one of the most controversial aspects of our struggle is the grasp of these scientific universal laws. Would you, therefore, talk about your party’s understanding of revolutionary theory, particularly as related to Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, and the anti-colonial wars of national liberation? So I wonder, would you speak on this problem?

CABRAL: You see, I think that all kinds of struggles for liberation obey a group of laws. The application of these laws to a certain case depends on the nature of the case. Maybe all these laws are applicable, but maybe only some, it depends. In science you know water boils at 100 degrees centigrade. It’s a law. Naturally, with the condition that we are speaking in centigrade degrees, this is a specification. What does it mean if we are measuring Fahrenheit - it’s not the same. And it is also only at sea level. When you go into the mountains this law is not true. It is sometimes more complex.

It’s the same in the field of the scientific character of the liberation struggle. Cuba, Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, and so on. Sometimes you can even explain conflicts between their people because of the different nature of their struggle, dictated by the different conditions of the countries - historical, economical, and so on.

I have to tell you that when we began preparing for our struggle in our own country, we didn’t know Mao Tse-tung. The first time I faced a book of Mao Tse-tung was in 1960. Our party was created in 1956. We knew less about the struggle of Cuba, but later we tried to know the experiences of other peoples. Some experiences we put aside because the difference was so great that it would waste time to study them. We think the experiences of other people are very important for you, principally to know things you should not do. Because what you do in your country you have to create yourself.

The general laws are very simple. For instance, the development of the armed fight in a country characterised by agriculture where most, if not all, of the population are peasants means you have to do to the struggle as in China, in Vietnam or in my country. Maybe you begin in the towns, but you recognise that this is not good. You pass to the countryside and mobilise the peasants. You recognise that the peasants are very difficult to mobilise under certain conditions, but you launch the armed struggle and step-by-step you approach the towns in order to finish the colonists.

For instance, this is scientific: in the colonial war there is a contradiction. What is it? It is that the colonial power in order to really dominate the country has to disperse its forces. In dispersing its forces it becomes weak - the national forces can destroy them. As you begin to destroy them they are obliged to concentrate, but when they concentrate they leave areas of the country you can control, administer and create structures in. You can tell me its not possible in the US, the US is not an agricultural country like this. But if you study deeply the conditions in your country maybe you will find that the law is applicable. This is what I can tell you because it is a big problem.

QUESTION (continued): I’d like to rephrase part of it. What I am trying to get at is how, in setting up a cadre training school that you set up in Conakry, did you access the revolutionary experiences of countries I mentioned? The point I am trying to drive at is not the form of waging a revolutionary struggle. I understand the differences in concrete conditions. I want to know how one moves through a colonial or a semi-feudal conditions into socialism (clearly the dominant revolutionary experience in the world). How were you able to set up a training program in which cadres were exposed to this information?

CABRAL: In the beginning we established in Conakry what you call a political school of militants. About one thousand people came from our country by groups. We first asked: Who we are? Where are we? What do we want? How do we live? What is our enemy? Who is this enemy? What can he do against us? What is our country? Where is our country? We asked things like this, step-by-step explaining our real conditions and explaining what we want, why we want it and why we have to fight against the Portuguese. Among all of these people some, step-by-step, approached other experiences. But the problem of going from a feudal or semi-feudal society or tribal society to socialism is a very big problem, even from capitalism to socialism.

If there are Marxists here they know that Marx said that capitalism created all the conditions for socialism. The conditions were created but never passed. Even then it is very difficult. This is even more reason for the feudal or semi-feudal tribal societies to jump to socialism - but it’s not a problem of jumping. It’s a process of development. You have to establish political aims based on your own condition, the ideological content of the fight. To have an ideology doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to define whether you are communist, socialist, or something like this. To have an ideology is to know what you want in your own condition.

We want in our country this: to have no more exploitation of our people, not by white people or by black people. We don’t want any more exploitation. It is in this way we educate our people - the masses, the cadres, the militants. For that we are taking, step-by-step, all the measures necessary to avoid this exploitation. How? We give to our people the instrument of control, the people to lead. And we give to our people all possibility to participate more actively each day in the direction of their own life.

Naturally, if an American comes he may say you are doing socialism in your country. This is a responsibility for him. We are not preoccupied with labels, you see. We are occupied in the content of the thing, what we are doing, how we are doing it, what chances are we creating for realising this aim. There are some societies that passed from feudal or semi-feudal stages to being socialist societies. But one of their specifics was having a state imposing this passage. We do not have this. We have to create for ourselves the instruments of the state inside our country, in the conditions of our history, in order to orientate all to a life of justice, work for progress and equality. Equality of chance for all people is the problem. The problem of equality is equality of chance. This is what I can tell you. This is a big discussion, philosophical if you want something like this.

QUESTION: What direct relationship does the OAU have with your party? You mentioned the OAU several times and I heard some things about the OAU, but I wanted to know whether or not it has been helpful to you, and if it has, in what ways?

CABRAL: Yes, they are good relations. Now we can even tell that we are nearly members of the OAU, because at the last summit conference in Rabat, they admitted the recognised liberation movements, like my party, to participate in the debate concerning their own cases. The relations are very good. We have the help of the OAU - not enough we think, but they are trying to increase this help and we think that in our own case, maybe next year, we will be a member, a full member of the OAU.

QUESTION (continued): Why? Do you see it as the organisation for Africa?

CABRAL: A real organisation for Africa? It depends. Now at this stage of the revolution in Africa, the OAU is a very good thing. It is such a good thing that imperialism is doing its best to finish it. Naturally, maybe for your ideas the OAU doesn’t answer well, doesn’t fully correspond to your hopes. Maybe you are right, but this is not the problem. In the political field, you have to know at each stage if you are doing the possible or not, and preparing the field for the possible for tomorrow or not. This is the problem.

QUESTION (continued): Yes, but how was it created and how is it being supported?

CABRAL: Oh, that’s a very big matter. You don’t know how it was created? They met in May 1963 in Addis Ababa, and they established a charter.

QUESTION (continued): Who is supporting this organisation?

CABRAL: Who is supporting it? The states - the African states? Yes, the African states. The imperialists - no, you are not right. You are not right, my sister. We can tell that some of the African states (interrupted)

QUESTION: (continued): If there is such an organisation why are we still where we are? It is just the leaders that elect to go there, not the kind of people like yourself, who are coming down to the masses and speaking the truth. These are neo-colonial leaders.

CABRAL: No. But that is not the problem. You are confused. You are making a mistake. One problem is the problem of the OAU. The OAU is an organisation of African states, it’s true. Are imperialists supporting the OAU? On the contrary, they do their best not to because there is a potential danger for them. The other problem is: are these African states all really independent? Some of them are neo-colonialist, but you have to distinguish this thing in order to do something. If you confuse all - it’s not possible.

QUESTION: (continued): But brother, why is it that each time the question of Pan-Africanism is brought to the discussion most of them take different views?

CABRAL: Oh, yes. You see you cannot demand all the African states to agree immediately on Pan-Africanism. Even if we discuss Pan-Africanism you would be surprised. I am for Pan-Africanism. I am for African unity. But we have to be for these things and do them when possible, not to do it now. You see, my sister, you here in the US, we understand you. You are for Pan-Africanism and you want it today. Pan-Africanism now! We are in Africa; don’t confuse this reaction against Pan-Africanism with the situation of the OAU. I can tell you, the head of state in Africa I admired the most in my life was Nkrumah.

QUESTION (continued): He was the only one. He was the father.

CABRAL: Nkrumah was not the father of Pan-Africanism. An American, Du Bois, was the father, if you want. Pan-Africanism is a means to return to the source. You see, it’s a very big problem. It’s not like this. Nkrumah told me in Conakry - unfortunately he is not alive, but I am not lying, I never lied in my life, he was one of my best friends, I’ll never forget him and you can read my speech at his memorial - you see he told me, ‘Cabral, I tell you one thing, our problem of African unity is important, really, but now if I had to begin again, my approach would be different.’

Unfortunately, I am leaving, but if I would like very much to speak with you in order to show you Pan-Africanism is a very nice idea; but we have to work for it, and it is not for me to accuse Houphouet-Boigny or Mobuto, because they don’t want it. They cannot want it! It is more difficult for some heads of state in Africa to accept African unity as defined by Nkrumah than it is for them to come here to the most racist of the white racists and tell them to accept equal rights for all Africa. You see, more difficult. It’s a great problem, my sister. And we think on this problem every day because our future concerns that.

We have a meeting at half past seven with the chairman of the decolonisation committee. We have to go there. It is about 20 minutes from here. I am late.

QUESTION: When will we see you again?

CABRAL: Again? I never know. It is difficult for me, but I hope in two years. Also for some of you, if you want, you can come to my country and see me and see our people.

QUESTION: How?

CABRAL: By paying the fare. (laughter)

QUESTION: What are some of the specific financial and political things we can do to further the struggle?

CABRAL: Personally I don’t agree with this question. I think that this meeting is a meeting of brothers and sisters. You represent several organisations. I am very glad because we want your unity. We know it’s very difficult - it’s more difficult to make your unity than Pan-Africanism maybe. But we would like you to consider this meeting a meeting between brothers and sisters trying to reinforce not only our links in blood, and in history, but also in aims. I am very glad to have been here with you and I deeply regret that it is not possible to be with you longer. Thank you very much.” BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

History Is A Weapon:

National Liberation and Culture

This text was originally delivered on February 20, 1970; as part of the Eduardo Mondlane (1) Memorial Lecture Series at Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, under the auspices of The Program of Eastern African Studies. It was translated from the French by Maureen Webster.

”When Goebbels, the brain behind Nazi propaganda, heard culture being discussed, he brought out his revolver. That shows that the Nazis, who were and are the most tragic expression of imperialism and of its thirst for domination--even if they were all degenerates like Hitler, had a clear idea of the value of culture as a factor of resistance to foreign domination.

History teaches us that, in certain circumstances, it is very easy for the foreigner to impose his domination on a people. But it also teaches us that, whatever may be the material aspects of this domination, it can be maintained only by the permanent, organized repression of the cultural life of the people concerned. Implantation of foreign domination can be assured definitively only by physical liquidation of a significant part of the dominated population.

In fact, to take up arms to dominate a people is, above all, to take up arms to destroy, or at least to neutralize, to paralyze, its cultural life. For, with a strong indigenous cultural life, foreign domination cannot be sure of its perpetuation. At any moment, depending on internal and external factors determining the evolution of the society in question, cultural resistance (indestructible) may take on new forms (political, economic, armed) in order fully to contest foreign domination.

The ideal for foreign domination, whether imperialist or not, would be to choose:

either to liquidate practically all the population of the dominated country, thereby eliminating the possibilities for cultural resistance;

or to succeed in imposing itself without damage to the culture of the dominated people--that is, to harmonize economic and political domination of these people with their cultural personality.

The first hypothesis implies genocide of the indigenous population and creates a void which empties foreign domination of its content and its object: the dominated people. The second hypothesis has not, until now, been confirmed by history. The broad experience of mankind allows us to postulate that it has no practical viability: it is not possible to harmonize the economic and political domination of a people, whatever may be the degree of their social development, with the preservation of their cultural personality.

In order to escape this choice--which may be called the dilemma of cultural resistance--imperialist colonial domination has tried to create theories which, in fact, are only gross formulations of racism, and which, in practice, are translated into a permanent state of siege of the indigenous populations on the basis of racist dictatorship (or democracy).

This, for example, is the case with the so-called theory of progressive assimilation of native populations, which turns out to be only a more or less violent attempt to deny the culture of the people in question. The utter failure of this "theory," implemented in practice by several colonial powers, including Portugal, is the most obvious proof of its lack of viability, if not of its inhuman character. It attains the highest degree of absurdity in the Portuguese case, where Salazar affirmed that Africa does not exist.

This is also the case with the so-called theory of apartheid, created, applied and developed on the basis of the economic and political domination of the people of Southern Africa by a racist minority, with all the outrageous crimes against humanity which that involves. The practice of apartheid takes the form of unrestrained exploitation of the labor force of the African masses, incarcerated and repressed in the largest concentration camp mankind has ever known.

These practical examples give a measure of the drama of foreign imperialist domination as it confronts the cultural reality of the dominated people. They also suggest the strong, dependent and reciprocal relationships existing between the cultural situation and the economic (and political) situation in the behavior of human societies. In fact, culture is always in the life of a society (open or closed), the more or less conscious result of the economic and political activities of that society, the more or less dynamic expression of the kinds of relationships which prevail in that society, on the one hand between man (considered individually or collectively) and nature, and, on the other hand, among individuals, groups of individuals, social strata or classes.

The value of culture as an element of resistance to foreign domination lies in the fact that culture is the vigorous manifestation on the ideological or idealist plane of the physical and historical reality of the society that is dominated or to be dominated. Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history, by the positive or negative influence which it exerts on the evolution of relationships between man and his environment, among men or groups of men within a society, as well as among different societies. Ignorance of this fact may explain the failure of several attempts at foreign domination--as well as the failure of some international liberation movements.

Let us examine the nature of national liberation. We shall consider this historical phenomenon in its contemporary context, that is, national liberation in opposition to imperialist domination. The latter is, as we know, distinct both in form and in content from preceding types of foreign domination (tribal, military-aristocratic, feudal, and capitalist domination in time free competition era).

The principal characteristic, common to every kind of imperialist domination, is the negation of the historical process of the dominated people by means of violently usurping the free operation of the process of development of the productive forces. Now, in any given society, the level of development of the productive forces and the system for social utilization of these forces (the ownership system) determine the mode of production. In our opinion, the mode of production whose contradictions are manifested with more or less intensity through the class struggle, is the principal factor in the history of any human group, the level of the productive forces being the true and permanent driving power of history.

For every society, for every group of people, considered as an evolving entity, the level of the productive forces indicates the stage of development of the society and of each of its components in relation to nature, its capacity to act or to react consciously in relation to nature. It indicates and conditions the type of material relationships (expressed objectively or subjectively) which exists among the various elements or groups constituting the society in question. Relationships and types of relationships between man and nature, between man and his environment. Relationships and type of relationships among the individual or collective components of a society. To speak of these is to speak of history, but it is also to speak of culture.

Whatever may be the ideological or idealistic characteristics of cultural expression, culture is an essential element of the history of a people. Culture is, perhaps, the product of this history just as the flower is the product of a plant. Like history, or because it is history, culture has as its material base the level of the productive forces and the mode of production. Culture plunges its roots into the physical reality of the environmental humus in which it develops, and it reflects the organic nature of the society, which may be more or less influenced by external factors. History allows us to know the nature and extent of the imbalance and conflicts (economic, political and social) which characterize the evolution of a society; culture allows us to know the dynamic syntheses which have been developed and established by social conscience to resolve these conflicts at each stage of its evolution, in the search for survival and progress.

Just as happens with the flower in a plant, in culture there lies the capacity (or the responsibility) for forming and fertilizing the seedling which will assure the continuity of history, at the same time assuring the prospects for evolution and progress of the society in question. Thus it is understood that imperialist domination by denying the historical development of the dominated people, necessarily also denies their cultural development. It is also understood why imperialist domination, like all other foreign domination for its own security, requires cultural oppression and the attempt at direct or indirect liquidation of the essential elements of the culture of the dominated people.

The study of the history of national liberation struggles shows that generally these struggles are preceded by an increase in expression of culture, consolidated progressively into a successful or unsuccessful attempt to affirm the cultural personality of the dominated people, as a means of negating the oppressor culture. Whatever may be the conditions of a people's political and social factors in practicing this domination, it is generally within the culture that we find the seed of opposition, which leads to the structuring and development of the liberation movement.

In our opinion, the foundation for national liberation rests in the inalienable right of every people to have their own history whatever formulations may be adopted at the level of international law. The objective of national liberation, is therefore, to reclaim the right, usurped by imperialist domination, namely: the liberation of the process of development of national productive forces. Therefore, national liberation takes place when, and only when, national productive forces are completely free of all kinds of foreign domination. The liberation of productive forces and consequently the ability to determine the mode of production most appropriate to the evolution of the liberated people, necessarily opens up new prospects for the cultural development of the society in question, by returning to that society all its capacity to create progress.

A people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from the oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture, which is nourished by the living reality of its environment, and which negates both harmful influences and any kind of subjection to foreign culture. Thus, it may be seen that if imperialist domination has the vital need to practice culturaloppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture.

On the basis of what has just been said, we may consider the national liberation movement as the organized political expression of the culture of the people who are undertaking the struggle. For this reason, those who lead the movement must have a clear idea of the value of the culture in the framework of the struggle and must have a thorough knowledge of the people's culture, whatever may be their level of economic development.

In our time it is common to affirm that all peoples have a culture. The time is past when, in an effort to perpetuate the domination of a people, culture was considered an attribute of privileged peoples or nations, and when, out of either ignorance or malice, culture was confused with technical power, if not with skin color or the shape of one's eyes. The liberation movement, as representative and defender of the culture of the people, must be conscious of the fact that, whatever may be the material conditions of the society it represents, the society is the bearer and creator of culture. The liberation movement must furthermore embody the mass character, the popular character of the culture--which is not and never could be the privilege of one or of some sectors of the society.

In the thorough analysis of social structure which every liberation movement should be capable of making in relation to the imperative of the struggle, the cultural characteristics of each group in society have a place of prime importance. For, while the culture has a mass character, it is not uniform, it is not equally developed in all sectors of society. The attitude of each social group toward the liberation struggle is dictated by its social group toward the liberation struggle is dictated by its economic interests, but is also influenced profoundly by its culture. It may even be admitted that these differences in cultural level explain differences in behavior toward the liberation movement on the part of individuals who belong to the same socio-economic group. It is at the point that culture reaches its full significance for each individual: understanding and integration in to his environment, identification with fundamental problems and aspirations of the society, acceptance of the possibility of change in the direction of progress.

In the specific conditions of our country--and we would say, of Africa--the horizontal and vertical distribution of levels of culture is somewhat complex. In fact, from villages to towns, from one ethnic group to another, from one age group to another, from the peasant to the workman or to the indigenous intellectual who is more or less assimilated, and, as we have said, even from individual to individual within the same social group, the quantitative and qualitative level of culture varies significantly. It is of prime importance for the liberation movement to take these facts into consideration.

In societies with a horizontal social structure, such as the Balante, for example, the distribution of cultural levels is more or less uniform, variations being linked uniquely to characteristics of individuals or of age groups. On the other hand, in societies with a vertical structure, such as the Fula, there are important variations from the top to the bottom of the social pyramid. These differences in social structure illustrate once more the close relationship between culture and economy, and also explain differences in the general or sectoral behavior of these two ethnic groups in relation to the liberation movement.

It is true that the multiplicity of social and ethnic groups complicates the effort to determine the role of culture in the liberation movement. But it is vital not to lose sight of the decisive importance of the liberation struggle, even when class structure is to appear to be in embryonic stages of development.

The experience of colonial domination shows that, in the effort to perpetuate exploitation, the colonizers not only creates a system to repress the cultural life of the colonized people; he also provokes and develops the cultural alienation of a part of the population, either by so-called assimilation of indigenous people, or by creating a social gap between the indigenous elites and the popular masses. As a result of this process of dividing or of deepening the divisions in the society, it happens that a considerable part of the population, notably the urban or peasant petite bourgeoisie, assimilates the colonizer's mentality, considers itself culturally superior to its own people and ignores or looks down upon their cultural values. This situation, characteristic of the majority of colonized intellectuals, is consolidated by increases in the social privileges of the assimilated or alienated group with direct implications for the behavior of individuals in this group in relation to the liberation movement. A reconversion of minds--of mental set--is thus indispensable to the true integration of people into the liberation movement. Such reonversion--re-Africanization, in our case--may take place before the struggle, but it is completed only during the course of the struggle, through daily contact with the popular masses in the communion of sacrifice required by the struggle.

However, we must take into account the fact that, faced with the prospect of political independence, the ambition and opportunism from which the liberation movement generally suffers may bring into the struggle unconverted individuals. The latter, on the basis of their level of schooling, their scientific or technical knowledge, but without losing any of their social class biases, may attain the highest positions in the liberation movement. Vigilance is thus indispensable on the cultural as well as the political plane. For, in the liberation movement as elsewhere, all that glitters is not necessarily gold: political leaders--even the most famous--may be culturally alienated people. But the social class characteristics of the culture are even more discernible in the behavior of privileged groups in rural areas, especially in the case of ethnic groups with a vertical social structure, where, nevertheless, assimilation or cultural alienation influences are non-existent or practically non-existent. This is the case, for example, with the Fula ruling class. Under colonial domination, the political authority of this class (traditional chiefs, noble families, religious leaders) is purely nominal, and the popular masses know that true authority lies with an is acted upon by colonial administrators. However, the ruling class preserves in essence its basic cultural authority over the masses and this has very important political implications.

Recognizing this reality, the colonizer who represses or inhibits significant cultural activity on the part of the masses at the base of the social pyramid, strengthens and protects the prestige and the cultural influence of the ruling class at the summit. The colonizer installs chiefs who support him and who are to some degree accepted by the masses; he gives these chiefs material privileges such as education for their eldest children, creates chiefdoms where they did not exist before, develops cordial relations with religious leaders, builds mosques, organizes journeys to Mecca, etc. And above all, by means of the repressive organs of colonial administration, he guarantees economic and social privileges to the ruling class in their relations with the masses. All this does not make it impossible that, among these ruling classes, there may be individuals or groups of individuals who join the liberation movement, although less frequently than in the case of the assimilated "petite bourgeoisie." Several traditional and religious leaders join the struggle at the very beginning or during its development, making an enthusiastic contribution to the cause of liberation.

But here again vigilance is indispensable: preserving deep down the cultural prejudices of their class, individuals in this category generally see in the liberation movement the only valid means, using the sacrifices of the masses, to eliminate colonial oppression of their own class and to re-establish in this way their complete political and cultural domination of the people.

In the general framework of contesting colonial imperialist domination and in the actual situation to which we refer, among the oppressor's most loyal allies are found some high officials and intellectuals of the liberal professions, assimilated people, and also a significant number of representatives of the ruling class from rural areas. This fact gives some measure of the influence (positive or negative) of culture and cultural prejudices in the problem of political choice when one is confronted with the liberation movement. It also illustrates the limits of this influence and the supremacy of the class factor in the behavior of the different social groups. The high official or the assimilated intellectual, characterized by total cultural alienation, identifies himself by political choice with the traditional or religious leader who has experienced no significant foreign cultural influences.

For these two categories of people place above all principles our demands of a cultural nature--and against the aspirations of the people--their own economic and social privileges, their own class interests. That is a truth which the liberation movement cannot afford to ignore without risking betrayal of the economic, political, social and cultural objectives of the struggle.

Without minimizing the positive contribution which privileged classes may bring to the struggle, the liberation movement must, on the cultural level just as on the political level, base its action in popular culture, whatever may be the diversity of levels of cultures in the country. The cultural combat against colonial domination--the first phase of the liberation movement--can be planned efficiently only on the basis of the culture of the rural and urban working masses, including the nationalist (revolutionary) "petite bourgeoisie" who have been re-Africanized or who are ready for cultural reconversion. Whatever may be the complexity of this basic cultural panorama, the liberation movement must be capable of distinguishing within it the essential from the secondary, the positive from the negative, the progressive from the reactionary in order to characterize the master line which defines progressively a national culture.

In order for culture to play the important role which falls to it in the framework of the liberation movement, the movement must be able to preserve the positive cultural values of every well defined social group, of every category, and to achieve the confluence of these values in the service of the struggle, giving it a new dimension--the national dimension. Confronted with such a necessity, the liberation struggle is, above all, a struggle both for the preservation and survival of the cultural values of the people and for the harmonization and development of these values within a national framework.’

ENDNOTES:

1. Eduardo Mondlane, was the first President of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). He was assassinated by Portuguese agents on Feb. 3, 1960.

We are African peoples. We have our own hearts, our own heads, our own history. It is this history which the colonialists have taken from us. Today, in taking up arms to liberate ourselves, we want to return to our history, on our own feet, by our own means and through our own sacrifices. African Party for the Independence of Guidean and Cabo Verde (PAIGC) - Chicago Committee for the Liberation of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea

Linking the struggles: Amilcar Cabral and his impact and legacy in the black liberation movement

Kali Akuno, Jan 22, 2014

“Of all the African political leaders none have made more profound theoretical and strategic contributions to the advancement of the black liberation movement than Amilcar Cabral. As long as capitalism, colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism, and neo-colonialism exist as forces that exploit and oppress African (and all) people, Cabral’s insights and analysis will always have relevance

‘Keep always in mind that the people are not fighting for ideas, for the things in anyone’s head. They are fighting…..for material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward, to guarantee the future of their children. National Liberation, War on Colonialism, building of peace and progress – independence – all that will remain meaningless for the people unless it brings a real improvement in the conditions of life.” Amilcar Cabral, from “Destroy the economy of the enemy and build our own economy’, 1965.[1]

Since the close of the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England and the end of the second great inter-imperialist war (better known as World War II) in 1945, the radical-wing of the Black Liberation Movement in the United States (US) has been inspired by and drawn many lessons from its reciprocal interactions with the national and social liberation movements of Africa (primarily from 1945 through 1994) and the Diaspora (particularly those of the Caribbean).

The Black Liberation Movement or BLM is the historic movement of people of African descent within the territories now occupied and claimed by the settler-colonial government of the United States for self-determination and social liberation in three primary (and often mutually inclusive) forms[2]:

• Repatriation back to Africa

• The creation of a sovereign, independent national-state for Black or New Afrikan people in the southeastern portion of what is presently the United States

• The socialist and/or anti-capitalist transformation of the United States by an anti-racist, anti-imperialist multi-national alliance

The radical elements of the BLM - composed primarily of revolutionary nationalists, socialists, communists, and anarchists – have over the years learned and incorporated many of the critical aspects of the theories and strategies of radical social transformation developed by many of the twentieth century intellectual and political towers of the African world revolution, such as Kwame Nkrumah, George Padmore, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Aime Cesaire, Constance Cummings-John, Sekou Toure, Leopold Senghor, Amy Jacques Garvey, CLR James, Julius Nyerere, Walter Rodney, Patrice Lumumba, Govan Mbeki, Frantz Fanon, Robert Sobukwe, Winnie Mandela, Abdias do Nascimento, Mariam Makeba, Steven Biko, Maurice Bishop, and Thomas Sankara[3]. Of all of these leaders and theoreticians from Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America however, none have made more profound theoretical and strategic contributions to the advancement of the BLM than Amilcar Cabral.

All of the above named figures made valuable contributions to the BLM, particularly in the realm of providing ideological clarity on various questions, such as the relevancy of Marxism, Leninism, and Maoism to the struggles of African peoples worldwide, the exploratory power of dialectical and historical materialism, and the necessity of fighting for a United States of Africa and a unified Pan-African world guided by scientific socialism.

What separates Cabral from the others however, is that his work provided detailed theoretical and strategic clarity on a number of fundamental questions that were critical to understanding the transition from “American colonialism” to neo-colonialism following the defeat of legalized white supremacy in the early 1960’s. Some of Cabral’s particular contributions centered on the following questions[4]:

• The limitations of national liberation within the capitalist world-system

• The internal material basis for neo-colonialism within colonized and oppressed nations and the critical dangers associated with this form of capitalist penetration and imperialist rule

• The ideological and theoretical weaknesses and shortcomings of the peoples movements for liberation and the detriments they pose to the success of the movements

• The centrality of culture to anti-imperialist resistance and the need to create a new culture through struggle to restore oppressed people into full agents of their own history and identity

• The imperative of class struggle within the oppressed nation and the necessity of class “suicide” amongst critical segments of the nation (or nation-class as Cabral himself stated), but most particularly the petit bourgeoisie who often constitute the leadership of the movements given their strategic location within the capitalist mode of production and its national/international hierarchies

All of these questions and issues have haunted the BLM since the 1970s, and continue to pose some of the most quintessential challenges confronting the movement. Although the historic development of Guinea-Bissau is profoundly different than that of the Black or New Afrikan nation contained within the United States, there are some fundamental dynamics regarding how colonized and oppressed peoples are subjected and exploited within the capitalist world-system established through European colonialism and imperialism, that can be generalized to address the varied examples of the colonial experience. Cabral’s works not only discerned generalities of the colonial phenomenon that were applicable to the New Afrikan context, they also provided critical specificities that can and are still being used by various forces of the BLM to sustain and advance the struggle for liberation.

Cabral’s theoretical insightful works did not spring from thin air. Cabral was the product of a rather unique nexus of historical conjunctures that enabled him to directly experience and engage the various dynamics he wrote about and reflected upon. Cabral developed his theories on the motive forces of history, colonialism, imperialism, questions of national liberation, neo-colonialism, class and class struggle within national liberation movements, the transition to socialism, and the centrality of culture and identity to resistance and social transformation from his unique social experiences, central location in the struggle against Portuguese colonialism, and his critical study of the numerous challenges and failures of the national liberation movements on the African continent in the 1950s and 60s.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A LEADER

Cabral was born in Guinea-Bissau in 1924 and was reared primarily in Cape Verde, a small island chain off the Northwest Coast of the African continent formerly ruled by Portugal. He attended university in Portugal and studied to be an agronomist. In the employment of the Portuguese colonial administration in the 1950s, Cabral was able to gain extensive knowledge of the cultures and social conditions of the various peoples of Guinea-Bissau and (to a lesser degree) Angola performing agricultural census studies. In September 1956, along with five other comrades from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, Cabral established the Partido Africano da Independecia da Guinea e Cabo Verde or PAIGC (which translated into English means the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde), which lead Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde islands to political independence in the 1970s. While living in Angola, also in 1956, Cabral collaborated with Mario de Andrade and Antonio Agostinho Neto to form the Movimento Popular Libertacao de Angola or MPLA (in English this translates into the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), which played a leading role in the liberation of Angola.

All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana 1958

In 1957, as part of a conference in solidarity with the Algerian anti-colonial movement in Paris, Cabral again partnered with Mario de Andrade and Antonio Agostinho Neto to form the Movimento Anti-Colonista or MAC (which translated into English means Anti-Colonialist Movement) to discuss strategies to overthrow Portuguese colonial rule. In 1958, Cabral attended the All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana organized by Kwame Nkrumah to coordinate support for the liberation movements from the existing independent nation-states and to unite the liberation movements on a continent wide basis [5]. In 1960, while in Tunisia, Cabral established the Frente Revolucionaria Africana para a Independencia Nacional das colonias Portuguesas or FRAIN (which translated into English translates into the Revolutionary Front for the National Independence of the Portuguese Colonies). FRAIN was established to coordinate the strategies and initiatives of the PAIGC and MPLA against Portuguese colonialism. In 1961, while in Casablanca, Morocco, Cabral helped to establish the Conferencia das Organizacoes Nacionalistas das Colonias Portuguesas or CONCP (which in English translates into Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies) to expand upon and replace FRAIN to include FRELIMO from Mozambique and the MLSTP from Sao Tome and Principe to coordinate resistance to Portuguese colonialism on the African continent. In January 1963, Cabral and the PAIGC initiated the armed phase of the resistance movement in Guinea-Bissau, which lead to its formal political independence from Portugal in September 1974[6].

As these initiatives illustrate, Cabral was a principle architect in the overthrow of Portuguese colonialism and the weakening of imperialist domination of Southern Africa via the white settler colonial regime in South Africa. As the spokesperson for the PAIGC, MPLA, and CONCP, Cabral was able to travel extensively throughout the African continent (and the world). Cabral used the knowledge gained on his travels to judiciously assess the many failures of the first wave of national liberation movements and the national-state governments produced by many of these movements. These combined experiences shaped his worldview, theory, and most importantly, his practice as a revolutionary nationalist, socialist, and internationalist. It was Cabral’s particular ability to systematically and scientifically summarizes these experiences in a coherent and concrete fashion that made his work applicable to the ongoing struggle for liberation of people of African descent in the United States.

UNITING WITH OUR “COMRADE”

“I am bringing to you - our African brothers and sisters of the United States - the fraternal salutations of our people in assuring you we are very conscious that all in this life concerning you also concerns us. If we do not always pronounce words that clearly show this, it doesn’t mean that we are not conscious of it. It is a reality and considering that the world is being made smaller each day all people are becoming conscious of this fact.

Naturally if you ask me between brothers and comrades what I prefer then if we are brothers it is not our fault or our responsibility. But if we are comrades, it is a political engagement. Naturally, we like our brothers but in our conception it is better to be a brother and a comrade. We like our brothers very much, but we think that if we are brothers we have to realize the responsibility of this fact and take clear positions about our problems in order to see if beyond this condition of brothers and sisters, we are also comrades. This is very important for us.

We try to understand your situation in this country. You can be sure that we realize the difficulties you face, the problems you have and your feelings, your revolts, and also your hopes. We think that our fighting for Africa against colonialism and imperialism is a proof of understanding of your problem and also a contribution for the solution of your problems in the continent. Naturally the inverse is also true. All the achievements towards the solution of your problems here are real contributions to our own struggle. And we are very encouraged in our struggle by the fact that each day more of the African people born in America became conscious of their responsibilities to the struggle in Africa.

Does that mean you have to all leave here and go fight in Africa? We do not believe so. That is not being realistic in our opinion. History is a very strong chain. We have to accept the limits of history but not the limits imposed by the societies where we are living. There is a difference. We think that all you can do here to develop your own conditions in the sense of progress, in the sense of history and in the sense of our total realization of your aspirations as human beings is a contribution for us. It is also a contribution for you to never forget that you are Africans.” Amilcar Cabral, from “Connecting the Struggles: An Informal Talk with Black Americans”, October 20, 1972, New York City.[7]

The BLM came to know Amilcar Cabral and his work through a dynamic set of interlocking organizations and networks linking activists based in the United States with the national liberation movements in Africa and Asia (the Vietnamese in particular), and revolutionary and progressive governments and social movements in Latin America (particularly Cuba), Africa (primarily Ghana, Tanzania, Guinea, and Algeria), Asia (particularly China) and the Eastern Bloc. These links consisted of survivors from the anti-communist repression and purges of the late 1940s and 50s, from groups like the Council on African Affairs (CAA) headed by the likes Alphaeus Hunton, Paul Robeson, and W.E.B. DuBois, which was formally active from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s[8]; to liberal organizations like the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), started in the early 1950s[9]; and a host of religious and academic institutions, Black and white, that had been active, particularly around missionary activities in Africa and supporting students from Africa to attend academic institutions in Europe and the United States since the 19th century. Through these links, activists engaged in progressive social movements were able to encounter their international counterparts via international conferences, student exchanges, solidarity missions, and campaigns.

Another critical link that facilitated the introduction and ongoing communication between revolutionaries from the continent with revolutionaries from the BLM in the United States were Black ex-patriots that lived in Europe (particularly London and Paris) or on the African continent, particularly in Ghana after it gained its independence in 1957 and was able to host a number of Black radical activists, intellectuals, and artists like George Padmore, W.E.B Dubois, and Shirley Graham-Dubois[10]. Conversely, African students and political exiles based in the United States and Europe played this critical role in reverse.

The first major student and youth oriented organization to introduce the BLM to the likes of African revolutionaries like Amilcar Cabral, Eduardo Mondlane, and others was the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee or SNCC. Over the course of its 9-year existence from 1960 to 1969, SNCC took several delegations to various parts of Africa to exchange lessons in the struggle and engage in international campaigns. SNCC’s first major trip to the continent was in the fall of 1964, when a delegation of 11 members visited the Republic of Guinea, led by President Ahmed Sekou Toure [11]. The SNCC delegation was exposed to an extensive amount of literature about the national liberation movements on the continent while in Guinea, some of it invariably from Cabral and the PAIGC, which was operating out of Guinea at that time [12].