Excerpts from Balanta B’urassa, My Sons: Those Who Resist Remain Volume 3

By the time of the arrival of the Portuguese, the first Europeans to make contact with Balanta people, Balanta culture was firmly based in an the Great Belief which mitigated against social hierarchies, state formation, and the resultant inequality that such systems of organization produce. As historian Walter Rodney pointed out,

“It is only the Balantas who can be cited as lacking the institution of kingship. At any rate there seemed to have been little or no differentiation within Balanta society on the basis of who held property, authority and coercive power. Some sources affirmed that the Balantas had no kings, while an early sixteenth-century statement that the Balanta ‘kings’ were no different from their subjects must be taken as referring simply to the heads of the village and family settlements. . . .as in the case of the Balantas, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . .”

This is of crucial significance for understanding the legal relationship that existed upon the first meeting of the Portuguese and Balanta as well as for resolving the current legal problems of the descendants of the Balanta people who were captured from their homeland, brought to the United States of America, and enslaved.

When the Portuguese first arrived on the shores of the Rio Cacheu and Rio Geba near where our Balanta ancestors were living, it was in no small part due to the Catholic Church, which played an authoritative role in the capture and enslavement of Balanta people. According to Wikipedia, Catholicism was introduced to what is now Portugal under the Roman Empire in the first half of the first millennium AD. The modern Portuguese state was founded in 1139 AD by Afonso Henriques during the Reconquista, in which the Catholic kingdoms of the northern Iberian Peninsula reconquered the South from the Islamic Moors. Crusaders from other Catholic realms aided the reconquest, which Portugal finished in 1249.

The 12th century saw the founding of eight new monastic orders, many of them functioning as Military Knights of the Crusades. Cistern monk Bernard of Clairvaux exerted great influence over the new orders and produced reforms to ensure purity of purpose. His influence led Pope Alexander III to begin reforms that would lead to the establishment of canon law.

John I of Portugal acceded in 1390 and ruled in peace, pursuing the economic development of his realm. The only significant military action was the siege and conquest of the city of Ceuta in 1415. By this step he aimed to control navigation of the African coast. But in the broader perspective, this was the first step opening the Arab world to medieval Europe, which in fact led to the Age of Discovery with Portuguese explorers sailing across the whole world.

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. It is stated in the Introduction to The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea Volume II that,

“Here, by the capture of Ceuta (area north of Fez on the African side of the Straight of Gibraltar south of Spain), Prince Henry gained a starting-point for his work; here he is said (probably with truth) to have gained his earliest knowledge of the interior of Africa; here especially he was brought in contact with those Sudan and Saharan caravans which, coming down to the Mediterranean coast, brought news, to those who sought it, of the Senegal and Niger, of the Negro kingdoms beyond the desert, and particularly of the Gold land of ‘Guinea.’ Here also, from a knowledge thus acquired, he was able to form a more correct judgment of the course needed for the rounding or circumnavigation of Africa, of the time, expense, and toil necessary for that task, and of the probable support or hindrance his mariners were to look for on their route. . . .

[T]he ‘Arabs and Moors’ of the early fifteenth century could give the Infant detailed and correct information, not only about the Barbary states and the trade-routes of the Sahara, but also about many of the Western and Central Sudan countries, and about the general course and direction of the ‘Guinea coast’ both to the west and south of the great African hump. Especially could they describe the kingdom of Guinea, centering around the town of Jenne on the Upper Niger, which was the chief market of their Negro trade in slaves, gold and ivory. This kingdom, then, reached almost to the Atlantic on the lower valley of the Senegal, where in earlier times a place called Ulil had been marked by Edrisis and other Arab geographers, as independent of Ghana but important for traffic. Also, the Moors were acquainted with the country of Tokrur, which may be supposed to occupy the upper valley of the Senegal, becoming perhaps in Prince Henty’s time, merely a province of Guinea. Further, they could give much information about the States of Timbuktu and Mali, to the east of Guinea, on the Middle Niger, about the gold land of Wangara, in the great bend to the south of that river, and about the Songhay, afterwards so powerful, whose capital was at Gao, at the extreme N.E. angle of the Negro Nile, or Joliba.”

Under king Edward, the colony at Ceuta rapidly became a drain on the Portuguese treasury, and it was realized that without the city of Tangier, possession of Ceuta was worthless. In 1437, Duarte's brothers Henry and Ferdinand persuaded him to launch an attack on the Marinid sultanate of Morocco. The resulting attack on Tangier, led by Henry, was a debacle. Failing to take the city in a series of assaults, the Portuguese siege camp was soon itself surrounded and starved into submission by a Moroccan relief army. In the resulting treaty, Henry promised to deliver Ceuta back to the Marinids in return for allowing the Portuguese army to depart unmolested. The Portuguese needed to find a new source of wealth.

The Papal Bull Dum Diversas issued by Pope Nicholas V, June 18, 1452, stated,

“we grant to you full and free power, through the Apostolic authority by this edict, to invade, conquer, fight, subjugate the Saracens and pagans, and other infidels and other enemies of Christ, and wherever established their Kingdoms, Duchies, Royal Palaces, Principalities and other dominions, lands, places, estates, camps and any other possessions, mobile and immobile goods found in all these places and held in whatever name, and held and possessed by the same Saracens, Pagans, infidels, and the enemies of Christ, also realms, duchies, royal palaces, principalities and other dominions, lands, places, estates, camps, possessions of the king or prince or of the kings or princes, and to lead their persons in perpetual servitude, and to apply and appropriate realms, duchies, royal palaces, principalities and other dominions, possessions and goods of this kind to you and your use and your successors the Kings of Portugal.”

Gomes Eannes de Azurara,, the royal chronicler of the King Don Affonso the Fifth of Portugal, gives the official purpose of the Portuguese exploration of the west coast of Africa:

“HERE beginneth the Chronicle in which are set down all the notable deeds that were achieved in the Conquest of Guinea, written by command of the most high and revered Prince and most virtuous Lord the Infant Don Henry, Duke of Viseu and Lord of Covilham, Ruler and Governor of the Chivalry of the Order of Jesus Christ. The which Chronicle was collected into this volume by command of the most high and excellent Prince, and most powerful Lord the King Don Affonso the Fifth of Portugal. . . .

And our Lord the King, considering that it was not convenient for the process of one only Conquest* that it should be recounted in many ways, although they all contribute to one result, ordered me to work at the writing and ordering of the history in this volume so that those who read might have the more perfect knowledge. . . .

We imagine that we know a matter when we are acquainted with the doer of it and the end for which he did it. And since in former chapters we have set forth the Lord Infant as the chief actor in these things, giving as clear an understanding of him as we could, it is meet that in this present chapter we should know his purpose in doing them. And you should note well that the noble spirit of this Prince, by a sort of natural constraint, was ever urging him both to begin and to carry out very great deeds. For which reason, after the taking of Ceuta (from the Moors in Morocco) he always kept ships well-armed against the Infidel, both for war, and because he had also a wish to know the land that lay beyond the isles of Canary and that Cape called Bojador, for that up to his time, neither by writings, nor by the memory of man, was known with any certainty the nature of the land beyond that Cape. Some said indeed that Saint Brandan had passed that way; and there was another tale of two galleys rounding the Cape, which never returned. But this doth not appear at all likely to be true, for it is not to be presumed that if the said galleys went there, some other ships would not have endeavored to learn what voyage they had made. And because the said Lord Infant wished to know the truth of this—since it seemed to him that if he or some other lord did not endeavor to gain that knowledge, no mariners or merchants would ever dare to attempt it — (for it is clear that none of them ever trouble themselves to sail to a place where there is not a sure and certain hope of profit)—and seeing also that no other prince took any pains in this matter, he sent out his own ships against those parts, to have manifest certainty of them all. And to this he was stirred up by his zeal for the service of God and of the King Edward his Lord and brother, who then reigned. And this was the first reason of his action.

The second reason was that if there chanced to be in those lands some population of Christians, or some havens, into which it would be possible to sail without peril, many kinds of merchandise might be brought to this realm, which would find a ready market, and reasonably so, because no other people of these parts traded with them, nor yet people of any other that were known; and also the products of this realm might be taken there, which traffic would bring great profit to our countrymen.

The third reason was that, as it was said that the power of the Moors in that land of Africa was very much greater than was commonly supposed, and that there were no Christians among them, nor any other race of men; and because every wise man is obliged by natural prudence to wish for a knowledge of the power of his enemy ; therefore the said Lord Infant exerted himself to cause this to be fully discovered, and to make it known determinately how far the power of those infidels extended.

The fourth reason was because during the one and thirty years that he had warred against the Moors, he had never found a Christian king, nor a lord outside this land, who for the love of our Lord Jesus Christ would aid him in the said war. Therefore, he sought to know if there were in those parts any Christian princes, in whom the charity and the love of Christ was so ingrained that they would aid him against those enemies of the faith.

The fifth reason was his great desire to make increase in the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ and to bring to him all the souls that should be saved,—understanding that all the mystery of the Incarnation, Death, and Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ was for this sole end—namely the salvation of lost souls—whom the said Lord Infant by his travail and spending would fain bring into the true path. For he perceived that no better offering could be made unto the Lord than this; for if God promised to return one hundred goods for one, we may justly believe that for such great benefits, that is to say for so many souls as were saved by the efforts of this Lord, he will have so many hundreds of guerdons in the kingdom of God, by which his spirit may be glorified after this life in the celestial realm. For I that wrote this history saw so many men and women of those parts turned to the holy faith, that even if the Infant had been a heathen, their prayers would have been enough to have obtained his salvation. And not only did I see the first captives, but their children and grandchildren as true Christians as if the Divine grace breathed in them and imparted to them a clear knowledge of itself.

But over and above these five reasons I have a sixth that would seem to be the root from which all the others proceeded: and this is the inclination of the heavenly wheels. For, as I wrote not many days ago in a letter I sent to the Lord King, that although it be written that the wise man shall be Lord of the stars, and that the courses of the planets (according to the true estimate of the holy doctors) cannot cause the good man to stumble; yet it is manifest that they are bodies ordained in the secret counsels of our Lord God and run by a fixed measure, appointed to different ends, which are revealed to men by his grace, through whose influence bodies of the lower order are inclined to certain passions. And if it be a fact, speaking as a Catholic, that the contrary predestinations of the wheels of heaven can be avoided by natural judgment with the aid of a certain divine grace, much more does it stand to reason that those who are predestined to good fortune, by the help of this same grace, will not only follow their course but even add a far greater increase to themselves. But here I wish to tell you how by the constraint of the influence of nature this glorious Prince was inclined to those actions of his. And that was because his ascendant was Aries, which is the house of Mars and exaltation of the sun, and his lord in the Xlth house, in company of the sun. And because the said Mars was in Aquarius, which is the house of Saturn, and in the mansion of hope, it signified that this Lord should toil at high and mighty conquests, especially in seeking out things that were hidden from other men and secret, according to the nature of Saturn, in whose house he is. And the fact of his being accompanied by the sun, as I said, and the sun being in the house of Jupiter, signified that all his traffic and his conquests would be loyally carried out, according to the good pleasure of his king and lord.”

- Gomes Eannes de Azurara, The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea

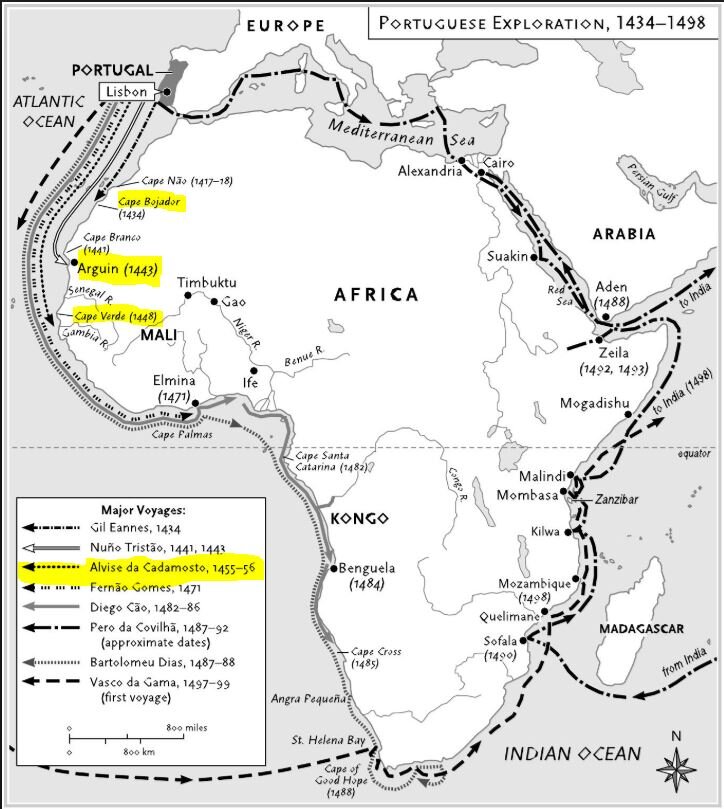

4,624 years AFTER our ancestors migrated from Ta-Nihisi just prior to Menes’ conquest of Ta-Nihisi and Ta-Meri, starting in the year 1424 AD, Henry the Navigator of Portugal sent 15 expeditions to explore the west coast of Africa. None reach any further than Cape Bojador, just south of the Canary Islands. In 1435, Gomes Eannes de Azurara traveled down the west African coast almost to the Tropic of Cancer.

Here is Gomes Eannes de Azurara’s account of the Portuguese’s first arrival in the land of Guinea:

“Gomez Pirez, who was there in that caravel of the King as chief captain, being a man of valour and authority, began to speak of his purpose . . . . ‘But as for you others, honorable sirs and friends, you know right well the will of the lord Infant; how much store he setteth on knowing somewhat of the land of the Negroes, and especially of the river of Nile, for which reason I am resolved to make my voyage to that land, toiling as much as I can to get at it . . . .”

And so those six caravels having set out, pursued their way along the coast, and pressed on so far that they passed the land of Sahara belonging to those Moors which are called Azanegues, the which land is very easy to distinguish from the other by reason of the extensive sands that are there, and after it by the verdue which is not to be seen in it on account of the gret dearth of water there, which causeth an exceeding dryness of the soil. . . .

Now these caravels having passed by the land of Sahara, as hath been said, came in sight of the two palm trees that Dinis Diaz had met with before, by which they understood that they were at the beginning of the land of the Negroes. And at this sight they were glad indeed, and would have landed at once, but they found the sea so rough upon that coast that by no manner of means could they accomplish their purpose. And some of those who were present said afterwards that it was clear from the smell that came off the land how good must be the fruits of that country, for it was so delicious that from the point they reached, though they were on the sea, it seemed to them that they stood in some gracious fruit garden ordained for the sole end of their delight. And if our men showed on their side a great desire of gaining the land, no less did the natives of it show their eagerness to receive them into it; but of the reception they offered I do not care to speak, for according to the signs they made to our men from the first, they did not intend to abandon the beach without very great loss to one side or the other. Now the people of this green land are wholly black, and hence this is called the Land of the Negroes, or Land of Guinea. Wherefore also the men and women thereof are called ‘Guineas,’ as if one were to say ‘Black Men.’ . . . And when the men in the caravels saw the first palms and lofty trees as we have related, they understood right well that they were close to the river of Nile, at the point where it floweth not the western sea, the which river is there called the Senegal (Canaga). For the Infant had told them that in little more than 20 leagues after the sighting of those tress they should look out for the same river, for so he had learnt from several of his Asanegue prisoners. . . .

And when they were close to its mouth, they let down their anchors on the seaward side, and the crew of the caravel of Vicene Diaz launched their boat, and into it jumped as many as eight men, and among them was that Esquire of Lagos called Stevam Affonso, of whom we have already spoken . . . .

And as all the eight were going in the boat, one of them, looking out towards the mouth of the river, espied the door of a hut, and said to his companions: ‘I know not how the huts of this land are built, but judging by the fashion of those I have seen before, that should be a hut that I see before me, and I presume it belongs to fishing folk who have come to fish in this stream. And if you think well, it seemeth to me that we ought to go and land beyond that point, in such wise that we may not be discovered from the door of the hut; and let some land, and approach from behind those sandbanks, and if any natives are lying in the hut, it may be that they will take them before they are perceived.’ Now it appeared to the others that this was good advice, and so they began to put it into execution. And as soon as they reached the land, Stevam Affonso leapt out and five others with him, and they proceeded in the manner that the other had suggested. And while they were going thus concealed even until they neared the hut, they saw come out of it a negro boy, stark naked, with a spear in his hand. Him they seized at once, and coming up close to the hut, they lighted upon a girl, his sister, who was about eight years old. This boy the Infant afterwards caused to be taught to read and write, with all other knowledge that a Christian should have; . . . so that some said of this youth that the Infant had bidden train him for a priest with the purpose of sending him back to his native land, there to preach the faith of Jesus Christ. But I believe that afterwards he died without ever reaching man’s estate. So those men entered into the hut, where they found a black shield made of hide, quite round in shape, a little larger than those used in that country, the which had in the middle of it a boss of the same hide as the shield itself, to wit, of an elephant’s ear, as was afterwards learnt from certain Guineas who saw it. . . . and when they had captured those young prisoners and articles of plunder, they took them forthwith to their boat. ‘Well were it, said Stevam Affonso to the others, ‘if we were to go through this country near here, to see if we can find the father and mother of these children, for judging by their age and disposition, it cannot be that the parents would leave them and go far off.’ The others said that he should go, with good luck, wherever he pleased, for there was nothing to prevent them following him. And after they had journeyed a short way Stevam Affonso began to hear the blows of an axe or some other iron instrument, with which some one was carpentering upon a piece of timber, and he stopped a little to assure himself of what he had heard, and put the others into the same attention. And then they all recognized that they were near what they sought. ‘Now,’ said he, ‘do you come behind and allow to go in front, because, if we all move forward in company, however softly we walk, we shall be discovered without fail, so that ere we come at him, whosoever he be, if alone, he must needs fly and put himself in safety; but if I go softly and crouching down, I shall be able to capture him by a sudden surprise without his perceiving me; but do not be so slow of pace that you will come late to my aid, where perhaps I may be in such danger as to need you.’

And they agreeing to this, Stevam Affonso began to move forward; and what with the careful guard that he kept in stepping quietly, and the intentness with which the Guinea labored at his work, he never perceived the approach of his enemy till the latter leapt upon him. And I say leapt, since Stevam Affonso was of small frame and slender, while the Guinea was of quite different build; and so he seized him lustily by the hair, so that when the Guinea raised himself erect, Stevam Affonso remained hanging in the air with his feet off the ground. The Guinea was a brave and powerful man, and he thought it a reproach that he should thus be subjected by so small a thing. Also he wondered within himself what this thing could be; but though he struggled very hard, he was never able to free himself, and so strongly had his enemy entwined himself in his hair, that the efforts of those two men could be compared to nothing else than a rash and fearless hound who has fixed on the some mighty bull. . . . But while those two were in their struggle, Affonso’s companions came upon them, and seized the Guinea by his arms and neck in order to bind him. And Stevam Affonso, thinking that he was now taken into custody and in the hands of the other, let go of his hair; whereupon, the Guinea, seeing that his head was free, shook off from his arms, them away on either side, and began to flee. And it was of little avail to the others to pursue him, for his agility gave him a great advantage over his pursuers in running, and in his course he took refuge in a wood full of thick undergrowth and while the others thought they had him, and sought to find him, he was already in his hut, with the intention of saving his children and taking his arms, which he had left with them. But all his former toil was nothing in comparison of the great grief which came upon him at the absence of his children whom he found gone – but as there yet remained for him a ray of hope, and he thought that perchance they were hidden somewhere, he began to look towards every side to see if he could catch any glimpse of them. And at this appeared Vicente Diaz, that trader who was the chief captain of that caravel to which the boat belonged wherein the others had come on land. And it appears that he, thinking that he was only coming out to walk along the shore, as he was wont to do in Lagos town, had not troubled to bring with him any arms you may well imagine, made for him with right good will.

An although Vicente Diaz saw him coming on with such fury, and understood that for his own defense it were well he had somewhat better arms, yet thinking that flight would not profit him, but rather do him harm in many ways, he awaited his enemy without shewing him any sign of fear. And the Guinea rushing boldly upon him, gave him forthwith a wound in the face with his assegai, with the which he cut open the whole of one of his jaws; in return for this the Guinea received another wound, though not so fell a one as that which he had just bestowed. And because their weapons were not sufficient for such a struggle, they threw them aside and wrestled; and so, for a short space they were rolling one over the other, each one striving for victory. And while this was proceeding, Vicente Diaz saw another Guinea one who was passing from youth to manhood; and he came to aid his countryman; and although the first Guinea was so strenuous and brave and inclined to fight with such good will as we have described, he could not have escaped being made prisoner if the second man had not come up; and for fear of him he now had to loose his hold of the first. And at this moment came up the other Portuguese, but the Guinea, being now once again free from his enemy’s hands, began to put himself in safety with his companion, like men accustomed to running, little fearing the enemy who attempted to pursue them. And at last our men turned back to their caravels, with the small booty they had already stored in their boats. . . .

And this may truthfully be affirmed according to the matters which at the beginning of this book I have related concerning the passage of Cape Bojador, and also from the astonishment which the natives of that land showed when they saw the first ships, for they went to them imagining they were fish, or some other natural product of the sea. But now returning to our history, after that deed was thus concluded, it was the wish of all the three captains to endeavor to make an honorable booty, adventuring their bodies in whatsoever peril might be necessary; but it appeareth that the wind veered sharply round to the south, wherefore it was convenient to set sail at once. And as they were cruising up and down in order to see what the weather purposed to do, the wind turned to the north, and with this they made their way towards Cape Verde, where Dinis Diaz had been the other year. And they went on as par as was possible for all the caravels to join them . . . .

We have already told of how Rodrigueannes and Dinis Diaz sailed in company, but this is the fitting place where it behoveth us to declare certainly all that happened to them. And it was so, that they, sailing in company after the manner we have already told, which we believe was after the scuttling of the pinnace, came to Cape Verde; and thence they went to the islands, and took in water, and knew for sure by the tracks all over them that other ships had already passed by that way. From there they began to make proof of the Guineas, in search of whom they had come there, but they found them so well prepared, that though they essayed to get on shore many a time, they always encountered such a bold defense that they dared not come to close quarters. ‘It may be,’ said Dinis Diaz, ‘that these men will not be so brave in the nighttime as by day; therefore, I wish to try what their courage is, and I can readily know it this next night.’ And this is in fact was put in practice, for as soon as the sun had quite hidden its light, he went on shore, taking with him two men, and came upon two inhabited places which seemed to him so large that he thought it best to leave them, for his expedition was not in order to adventure anything, but only that he might advise his other comrades of what they should do. Then he returned to the ship and there described to Rodrigueannes and the others all that he had found. ‘We,’ said he, ‘should be acting with small judgment, were we wishful to adventure a conflict like this, for I discovered a village divided into two large parts full of habitations you know that the people of this land are not so easily captured as we desire, for they are very strong men, very wary and very well prepared in their combats. . . . ”

Consider now that if Prince Henry’s purpose was the saving of souls, why would his men capture and enslave the first boy and girl they met instead of coming in peace and establishing a friendly relationship? How does literally kidnapping two children become pleasing to God, and why would such victims want to praise and worship such a God and terrible people?

The question at hand, however, is were the actions of the Portuguese lawful or legal? What right, by what authority, did the Portuguese presume to be operating?

The Sovereign Claim of Guinea Against Slavery

Herman L. Bennett, in African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern Atlantic, writes,

“In always already conflating African with slave and then condensing the slave’s relationship to the Western legal corpus down to the domain of property, slavery scholars – by projecting the cultural logic of an eighteenth-century market society onto earlier manifestations of bondage – ascribe unwarranted hegemony to Roman law. . . .

The fifteenth-century European legal corpus, by conceding dominium to infidels and pagans, implicitly recognized a sovereign African existence that preceded the human calculus transforming subjects into captives and slaves. Based on an established corpus of thought, law, and theology configuring Christian institutional relations with non-Christians, African polities wielded legal tender in the Christian imaginary. . . .

Even as extra ecclesiam, Guinea’s inhabitants, both infidels and pagans, had natural rights. In asserting its authority over the extra ecclesiam, who, in turn, acquired additional obligations and rights, the Church complicated matters.

At the most elemental level, natural law acknowledged native (African) sovereignty even as Christian thought, theology, and law sanctioned the enslavement of Africans. . . .

In contending with Portugal’s encounter with Guinea’s inhabitants and subsequently adjudicating over Portuguese and Castilian territorial claims in the Atlantic, successive fifteenth-century popes drew on a canonical tradition dating from Innocent IV’s thirteenth-century commentary. Before his election as Pope Innocent IV in 1243, Sinibaldo Fieschi was an influential canonist. As Pope (1241-1254), the erstwhile canonist took an active interest in Christian-Moslem relations since the Christian Crusades, the Reconquista (Spanish and Portuguese for ‘reconquest’ is a name used in English to describe the period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula of about 780 years between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada to the expanding Christian kingdoms in 1492), and Christian territorial expansion lacked a firm legal basis in canon law. In his influential commentary, Innocent IV raised the question, ‘Is it licit to invade the lands that infidels possess, and if it is licit, why is it licit?’ According to one leading scholar, ‘Innocent was not . . . interested in justifying the crusades; the general theory of the just war did that. What interested him was the problem of whether or not Christians could legitimately seize land, other than the Holy Land, that the Moslems occupied. Did . . . Christians have a general right to dispossess infidels everywhere?’ Innocent acknowledged that the law of nations had supplanted natural law in regulating human interaction, such as trade, conflict, and social hierarchies. Similarly, the prince replaced the father, as the ‘lawful authority in society’ through God’s provenance, manifesting his dominium in the monopoly over justice and sanctioned violence.

In outlining his opinion, Innocent delineated a temporal domain that was simultaneously autonomous yet subordinate to the Church. Laws of nations pertained to secular matters, a domain in which a significant tendency in the Church, known as ‘dualism,’ showed increasingly less interest. But in spiritual matters, the pope’s authority prevailed, since all humans were of Christ, though not with the Church. ‘As a result,’ the medievalist James Muldoon notes, ‘the pope’s pastoral responsibilities consisted of jurisdiction over two distinct flocks, one consisting of Christians and one comprising everyone else.’ Since the pope’s jurisdiction extended de jure over infidels, he alone could call for a Christian invasion of an infidel’s domain. Even then, however, Innocent maintained that only a violation of natural law could precipitate such an attack. By adhering to the beliefs of their gods, infidels and pagans did not violate natural law. Thus, such beliefs did not provide justification for Christians to simply invade non-Christian polities, dispossess its inhabitants of their territory and freedom, or force them to convert. Innocent IV’s theological contribution resided in the fact that he accorded pagans and infidels dominium and therefore the right to live beyond the state of grace. . . .

‘by the end of the fourteenth century Innocent IV’s commentary . . . had become the communis opinion of the canonists.’

A half century later, the imperial activities of Christian rulers again raised the issue about the infidel’s dominium. . . . Despite the shifting alliance characterizing Church-state relations in the late Middle Ages, temporal authorities in Christian Europe legitimized their rule and defined their actions on scriptural grounds. Christianity represented their ontological myth, the source of their traditions, and the banner under which they marched against the infidels. Initially, the Christian princes manifested some reluctance to distance themselves from this founding ideology, since to discard Christianity would mean that their dominium merely rested on the might of one particular lineage over another. Moreover, by abandoning the pretense to just war against the infidels, Christian sovereigns risked revealing that profit motivated their desire for expansion. In the context of the late Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period, commercial considerations stood in opposition to a Christian sovereign’s purported interests in honor and justice. In the early modern period, Christianity still served multiple purposes: it legitimized the ascendancy of a particular noble house while sanctioning elite dominium over the nonelite. In the face of powerful noble lineage, the position of the nascent absolutist rulers remained tenuous at best, and the prince was reluctant to dispense with the protective veneer that even diminished papal authority accorded. Still, the ambitious Iberian sovereigns manifested a willingness to interpret canon law in a manner that furthered their claims over infidels and Christians. . . .

Developments in Christendom also brought the dominium of the extra ecclesiam under renewed scrutiny. Since the Church defined all nonbelievers, including Saracens (a widely used term for infidels or those who willfully rejected the faith) and pagans (individuals who existed in ignorance of the faith) as the extra ecclesiam, it used the same laws and traditions in their treatment. In effect, the Church did not distinguish between the non-Christian minority in Europe and the extra ecclesiam residing beyond its de facto jurisdiction. Therefore, laws and practices shaping Church-state relations with nonbelievers in Europe set the precedent for Christian interaction with non-Christians in the wider Atlantic world. Beginning in the thirteenth century and in the context of the Reconquista, some Christian lords on the Iberian Peninsula started undermining the corporate bodies of Jews and Saracens by ordering those populations to adhere to Christian legal precepts and Iberian customary laws. While indicative of the Christians’ victory over the Moors, such practices represented a departure from Reconquista ethics. Throughout much of the Reconquista, victorious Christians and Moors often allowed their adversaries who remained under their territorial jurisdiction to adhere to their own beliefs and traditions. By the thirteenth century, when the tide favored Christians, the victorious rulers displayed less willingness to respect Moorish and Jewish corporate institutions and practices. This intransigence flourished at the very moment that Castilian scholars rediscovered Roman civil law, which they codified along with their customary practices in the Siete Partidas. Following this legal transformation, the Christian monarchs continued restricting the judicial autonomy of their Jewish and Moorish subjects. In 1412, this culminated in the most draconian legislation to date when it ‘forbade Jews and Moslems alike to have their own judges. Thenceforth, their cases, civil and criminal, were to be tried before ordinary judges of the districts where they lived. Criminal cases were to be decided according to Christians custom. . . .’

Though inimical to Innocent IV’s commentary granting the extra ecclesian dominium, the practice of curtailing Jewish and Moorish traditions reflected the ascendant hegemony of Hispania’s Christian rulers. These sovereigns, though zealous Christians, saw all corporate privileges as a threat to their centralizing aspirations. In their opinion, the inhabitants of their territory represented their subjects. Jews and Moors were not an exception. By their actions, Hispania’s Christian rulers contrived new forms of personhood. In a world defined by corporations with their accompanying rights and obligations, Jews and Moors embodied corporate-less beings that Christian authorities compelled to adhere to Christian laws and customary norms thereby forsaking their own legal traditions and customs. By undermining Jewish and Moorish courts, the Christian rulers redefined more than their relations to Jews and Moors. As they dismantled the courts that had once enabled Jews and Moors to reproduce their distinctive juridical status, the Catholic sovereigns actually reconstituted the meaning of being a Jew or a Moor. Standing before Christian courts and officials whose rulings owed much to Christian ethics, the various diasporic populations – Jews, Moors, and Africans- lacked the protective shield of a culturally sanctioned corporate status. As such, they embodied one of the distinguishing features of the early modern period – individualism.

Understanding Portugal’s initial encounter with Guinea’s inhabitants requires juxtaposing the Church’s historical provenance over the extra ecclesiam against the secular state’s ascendancy. Despite the precedent established by Innocent IV’s commentary, temporal authorities drastically transformed their institutional interaction with the non-Christian minority, which carried over into their relationship with the peoples of Guinea. As the Church’s hegemony receded, the monarch’s power expanded, but dogma continued to affect the secular authorities’ practices and nascent traditions. Much of the imperial activity in the fifteenth century represented secular expansion that the papacy approved after the fact. Despite the secular nature of the Infante’s imperial activity Henrique (Prince Henry) continued to rely on the Reconquista rhetoric of just war and Christian conversion. But the motives informing Gomes Eannes de Zurara’s text and the language through which the Portuguese represented the ‘conquest of Guinea’ also underscores a discursive shift . . . . Irrespective of the transformations in Europe, which signaled a shift in the relationship between Christians and the extra ecclesiam, secular expansion, for reasons of legitimacy, had to contend with a tradition that acknowledged the infidels’ and pagans’ dominium and right to live as sinners. Grace, in other words, did not form the basis on which the rule of law rested. Non-Christian princes did, therefore, wield legitimate authority and constitute sovereign temporal authorities. As the Portuguese and subsequently the Castilians ventured farther south into the ‘land of the blacks,’ they constantly had to contend with theoretical and practical recognition that Guinea did not represent terra nullius (land that is legally deemed to be unoccupied or uninhabited).

Here is the first “legal” question – when Innocent IV concluded that “the law of nations had supplanted natural law in regulating human interaction “ and “the prince replaced the father, as the ‘lawful authority in society’ through God’s provenance, manifesting his dominium in the monopoly over justice and sanctioned violence,” how did that apply to our Balanta ancestors to whom, by natural law and customary law, “the family is the sole effective social and political unit”?

Wikipedia states:

“In his Institutiones (161 AD), the Roman jurist Gaius wrote that:

[Slavery is] the state that is recognized by the ius gentium in which someone is subject to the dominion of another person contrary to nature.

— Gaius, Institutiones 1.3.2

The 1st century BC Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus indicates that the Roman institution of slavery began with the legendary founder Romulus giving Roman fathers the right to sell their own children into slavery, and kept growing with the expansion of the Roman state. Slave ownership was most widespread throughout the Roman citizenry from the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) to the 4th century AD. The Greek geographer Strabo (1st Century AD) records how an enormous slave trade resulted from the collapse of the Seleucid Empire (100–63 BC).

The Twelve Tables, Rome's oldest legal code, has brief references to slavery, indicating that the institution was of long standing. In the tripartite division of law by the jurist Ulpian (2nd century AD), slavery was an aspect of the ius gentium, the customary international law held in common among all peoples (gentes). The "law of nations" was neither natural law, which existed in nature and governed animals as well as humans, nor civil law, which was the body of laws specific to a people. All human beings are born free (liberi) under natural law, but slavery was held to be a practice common to all nations, who might then have specific civil laws pertaining to slaves. In ancient warfare, the victor had the right under the ius gentium to enslave a defeated population; however, if a settlement had been reached through diplomatic negotiations or formal surrender, the people were by custom to be spared violence and enslavement. The ius gentium was not a legal code, and any force it had depended on "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct."

Slavery violated our Balanta ancestors’ Great Belief and egalitarian society. We intentionally did not form centralized state societies because of the inequality it produced. Thus, our Balanta ancestors could not have been a party to any ius gentium, the customary international law held in common among all peoples pertaining to slavery because it violated our customs. Therefore, there could be no “reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct”. Not only was slavery “illegal”, it was unfathomable to our Balanta ancestors.

It is customary, however, for Balanta to settle conflict by means of the moranca (household) or tabanca (group of households) and it was customary, as Bennet shows, for the Europeans to respect sovereign claims. Balanta sovereign claims reside at the level of the moranca (household), and this is inconceivable to the European mind.

In discussing this first encounter between our Balanta ancestors and the Portuguese Christians, Herman Bennet writes,

“With this auspicious inauguration, Gomes Eanes de Zurara, the House of Avis’s royal chronicler and archivist, introduced one of Portugal’s foundational texts: The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea. Commissioned by the House of Avis, Zurara knew only too well that historical writing represented a construction- a process whereby patrons determined the primacy of certain narratives over others. . . . In this narratives production, the trope of Reconquista – the ideological myth of unwavering Christian opposition to Muslim domination of the Iberian Peninsula – was so pervasive that it conflated Islamic Moors and pagan Africans [Siphiwe note: and our “Saracentic” Balanta ancestors], a representational gesture that precluded first the Portuguese and subsequently Castilians from marveling at their novel encounter with Guinea’s inhabitants. . . .The contrast with ‘Indians’ or even Europeans did not, however, elicit images of a homogenous ‘black’ subject. The discourse of Reconquista, but especially canon law, wrought juridical differences among ‘Africa’s’ inhabitants – differences manifested in the language of sovereignty or the lack thereof. . . .

In the context of the Reconquista – the Christian-Moorish conflict over the possession of the Iberian Peninsula that began in the eighth century – conquista represented a Christian sovereign’s dominium extending from a permanently settled village, town or city to the immediate hinterland and its inhabitants. But as The Chronicle unfolds, the Portuguese do not act in accordance to existing definitions of conquest. During their initial voyages along Guinea’s coast, the Portuguese not only eschew establishing a settlement, either peacefully or by force; they also make no effort to contract a treaty so as to acquire a territorial claim to ‘the land of blacks.’ With several noteworthy exceptions, the initial Portuguese encounter with Guinea constituted chattel raids. Such raids underscore the commercial imperatives of those ‘notable deeds’ and of Portugal’s conquests. With Christian ascendancy over the Moors largely ensured, the Portuguese and subsequently the Castilian temporal authorities attached new meanings to the term conquista. In the Reconquista’s waning decades, commerce and the possession of bodies, not territory, signified the ‘notable deeds. . . . achieved in the Conquest of Guinea.’ Despite their increasing temporal preoccupations, the princes and their chroniclers employed the conquest rhetoric so as to invoke images of Christian Crusades, just wars, and the conversion of infidels. For Portugal’s princes, Christian zeal played a connected yet secondary role to profit and strategic knowledge about commercial opportunities. . . .

Prompted southward by profit, the Portuguese charted Guinea’s physical and human landscape in accordance with their commercial sensibility. While the quest for profits propelled the Portuguese encounter with Guinea’s inhabitants, long-standing practices scripted the interaction between Christians and non-Christians and led Zurara to depict the Portuguese expeditions as a Reconquista. During the Reconquista, Christians enslaved infidels under the pretext of a just war, yet irrespective of these religious imperatives, ransom still represented a viable option. But when blackamoors, as opposed to Moors, became the victims of the Portuguese raids, the practice of accepting ransom for religious captives ended – since they quickly became slaves for life. This transformation underscores developments in the emergent Atlantic economy and the concomitant evolution of an early modern commercial sensibility that gradually untangled itself from its Christian foundations. . . . Consequently, the Church continued to accord infidels and pagans the right to have an existence beyond the state of grace, while consenting that those who had been legitimately enslaved could be reduced to chattel. Yet even among chattel, the Church maintained some dominion – especially over their souls – and in an effort to affect the Christian republica’s spiritual well-being imposed itself between masters and their property. . . .

As the Portuguese shifted their gaze southward under Henrique’s influence, their motive was commerce not conversion. Henrique wanted ‘to know the land’ so that ‘many kinds of merchandise might be brought to this realm, which would find a ready market.’ At this historic moment, however, commerce could not enter posterity as the sole motive behind a noble’s behavior. Thus, in listing five reasons why the Infante manifested an interest in ‘the land beyond,’ Zurara wrote that Henrique’s final reason represented a ‘great desire to make increase in the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ.’

In 1434, under the Infante’s encouragement ‘to gain . . . honour and profit,’ the squire Gil Eanes finally reached ‘the land beyond’ when he rounded the Cape of Bojador. . . and tcAccording to Zurara, they ‘saw a country very different from that former one – for that was sandy and untilled, and quite treeless, like a country where there was no water – while this other land they saw to be covered with palms and other green and beautiful trees.’ Eventually the Portuguese rendered geographical dissimilarities into customary and ultimately juridical distinctions, separating Moors from blackamoors. The quest ‘to know’ and the concomitant desire for profit encouraged the Portuguese penchant for specificity. In his quest to offer the ‘more perfect knowledge’, Zurara revised his earlier observations that Guinea included the ‘land of the Moors’. . . .

In 1441, twenty-six years after the conquest of Ceuta, the Portuguese expedition under Antao Goncalves landed near Cabo Blanco in present-day Mauritania. Following a brief skirmish ‘in the land of Guinea’ with a ‘naked man following a camel’, the Portuguese enslaved their first Moor. . . . By their actions, the Portuguese launched the transatlantic slave trade in whose wake the early modern African diaspora emerged and in which the ‘slave’ constituted the charter subject. Through the capture of the “Mooress’, but in particular by marking her as distinct from the Moors on the basis of juridical status and phenotype, the Portuguese introduced a taxonomy that distinguished Moors from blackamoors, infidels from pagans, and Africans from blacks, sovereign from sovereignless subjects, and free persons from slaves. Shortly thereafter, the Portuguese employed this human measure, formulated via a black woman’s body, so as to delineate who could be ‘legitimately’ enslaved.

Though the Portuguese discerned a difference between the Moors and the blackamoors, this initially did not preclude the enslavement of the former. Arriving in Goncalves’s wake, Nuno Tristao ‘brought with him an armed caravel’ intent on capturing ‘some of the people of the country.’ On learning of his compatriots’ deeds, the zealous Nuno Tristao insisted that ‘what is still better. . . [is] for us to carry many more; for . . . profit.’ According to Zurara, Tristao led a nocturnal raid against the Moors who Goncalves had previously sighted. In the ensuing raid, the Portuguese took an additional ten ‘prisoners’, including a noble named Adahu. . . .

In Sagres, Zurara’s concern shifted from the profit obtained through raiding to the captives’ spiritual salvation. Zurara insisted that ‘the greater benefit was theirs, for though their bodies were now brought into some subjection, that was a small matter in comparison of their souls, which would now possess true freedom for evermore.’ After recounting the intricacies of the captives’ partition, Zurara directed his attention to the noble Adahu. ‘As you know,’ Zurara stated, ‘every prisoner desireth to be free, which desire is all the stronger in a man of higher reason or nobility.’ ‘Seeing himself held in captivity,’ Adahu offered Goncalves ‘five or six Black Moors’ in return for his freedom and promised a similar ransom for two youths that were also held captive. Tempted by his desire to ‘serve the Infante his lord’ who was intent on know[ing] part of that land,’ Goncalves immediately committed himself to another expedition that included Adahu and the two youths. ‘For as the Moor told’ him, ‘the least they would give for them would be ten Moors.’ According to Zurara, ‘It was better to save ten souls than three – for though they were black, yet had they souls like the others, and all the more as these blacks were not of the lineage of the Moors but were Gentiles, and so the better to bring into the path of salvation.’ In addition to the quantity of souls, Adahu promised ‘the blacks could give. . . .news of the land further distant.’

Prompted by profit, souls and strategic curiosity, the Portuguese expedition under Goncalves landed near the Rio d’ Ouro (River of Gold) where they met two Moors who instructed them to wait. The Moors returned with an entourage numbering a hundred ‘male and female,’ thus revealing ‘that those youth were in great honour among them.’ Goncalves exchanged his two captives for ‘ten blacks, male and females, from various countries.’ . . .

The episode underscored Portuguese awareness of differences among Africans. Accordingly, it was the Moor, who, because of his superior status, valued freedom more than blacks. The Portuguese quickly equated status with sovereignty and the lack thereof with the legitimate enslavement of certain individuals. Though the Portuguese captured both Moors and the ‘black Mooress,’ they had already started distinguishing between sovereign ‘Moorish’ subjects and those ‘Moors,’ ‘Negros,’ and ‘black’ that they could legitimately enslave. Zurara observed that the ‘black Mooress,’ unlike the valiant yet vanquished ‘Moor,’ represented the ‘legitimately’ unfree. . . . As the Portuguese encountered more of Guinea’s inhabitants the terms ‘Black Moors’ ‘blacks,’ “Ethiops,’ ‘Guineas,’ and ‘Negroes,’ or the descriptive terms to which a religious signifier was appended such as ‘Moors. . . [who] were Gentiles’ and ‘pagans’ gradually constituted the rootless and sovereignless – and in many cases, simply ‘slaves’.

As the Portuguese perceived distinctions among the peoples they encountered and began acting in accordance with these perceptions, Infante Henrique sought to cultivate papal approval for his subjects’ deeds. By linking Portugal’s activities in Guinea with the conquest of Ceuta, the Infante stressed how spiritual imperatives motivated exploration along the Atlantic littoral. In his diplomatic entreaty, Infante Henrique minimized the commercial incentive and fashioned the ‘toils of that conquest’ into a ‘just war’ under the banner of a Christian Crusade. In his response a papal bull – Eugenius IV unwittingly underscored the extent of the Infante’s misrepresentation and the Church’s willingness to perpetuate this fiction. Romanus pontifex (1433), the first in a series of papal bulls issued during the fifteenth century that regulated Christian expansion, sanctioned the Infante’s request and Portugal’s alleged mission in Guinea since ‘we strive for those things that may destroy the errors and wickedness of the infidels and . . . our beloved son and noble baron Henry . . . .purposeth to go in person, with his men at arms, to those lands, that are held by them and guide his army against them.’ For Pope Eugenius, the Infante’s alleged ‘war’ constituted a Christian counteroffensive, which if successful would undermine the ‘Turks’ military presence in the Mediterranean. . . . Though Pope Eugenius claimed that his ‘beloved son’ and ‘Governor of the Order of Christ’ intended to ‘make war under the banner of the said order against. . . Moors and other enemies of the faith,’ Henrique’s and his subjects’ motives did not resonate in the ‘aforesaid war.’ The territorial charter granted by Portugal’s regent prince, Infante Pedro to his brother Henrique, included exclusive jurisdiction over Guinea and thus underscores the Infante’s true interests and commercial acumen. Desiring legitimacy for his commercial imperatives and wanting to prevent other princes from encroaching on Portugal’s ‘conquests,’ Infante Henrique invoked the rhetoric of a just war so as to solicit papal patronage. In order to receive the charter from Portugal’s regent and his brother, Infante Pedro, Henrique did not need to mask his intentions in the trope of the Reconquista. Through tactical representation, Henrique acquired an exclusive character to mediate between Christians and Guinea’s inhabitants.

In soliciting papal approval, Henrique manifested the ways in which the early modern prince – a temporal authority with decidedly secular interests – continued to rely on Christian legitimization. Henrique, by his actions, acknowledged the Church’s imagined jurisdiction beyond Christendom’s borders and over the extra ecclesiam. . . .”

West Africa: Quest For Gold and God 1475-1578 by John W. Blake recalls,

“The main purpose of the Portuguese crown was always to exploit the Guinea trades to the highest royal advantage, but its methods varied, for different schemes were tried, according to the particular preference of the reigning king. . . . Nevertheless, through all the superficial fluctuations of economic policy, we may discern a constant effort to make profit by the creation of monopolies. . . . Private merchants, the subjects of soverigns who have no legal claim to Guinea, will equip ships to make the traffic in spite of papal prohibitions, Portuguese protests and threats, and the lurking dangers of the Ocean. . . .

The events of the war with Castile had shown that, if the Guinea monopoly was to be upheld, steps must be taken to protect it. Moreover, there were signs of unwelcome activity in the ports of Flanders and England, and indications that Florentine, Genoese, English and Flemish merchants wanted to share in the gold trade. These reasons, combined with vague fears of what the future might have in store, drove the Portuguese, immediately after the return of Columbus from his first voyage of discovery to the west, to seek a confirmation of their monopoly. Their efforts were rewarded in 1493-4 by papal bulls and the Treaty of Tordesillas. . . .

The two powers ceased, after 1494, to compete in West Africa. Nevertheless, a bilateral treaty was insufficient to deter the governments of France and England from encouraging their mariners to venture in the Guinea Traffic. . . .

Fifty years of quiet consolidation in Guinea came to an abrupt end in 1530. . . . Portuguese merchants, thus left alone, seized the opportunity to build up a profitable trade, and Portuguese missionaries undertook the evangelization of many of the negro tribes. . . .

Until 1553, the part played by Englishmen in West Africa was negligible.