If you have an ancestor from the Senegambia region (like Blanata, Mende or Temne) that survived the middle passage and you have an English name or surname, then you need to read this article, especially if you are doing genealogy research. The following is an excerpt from and comments about Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s excellent book, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links.

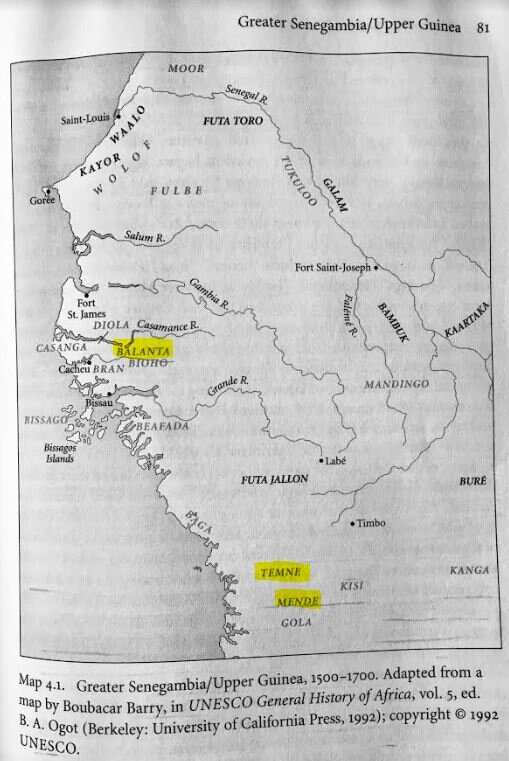

“During the first woo years of the Atlantic slave trade, Guinea meant what Boubacar Barry defines as Greater Senegambia: the region between the Senegal and the Sierra Leone rivers. In Arabic, “Guinea” meant “Land of the Blacks.” It referred to the Senegal/Sierra Leone regions between the Senegal and the Sierra Leone regions alone. In early Portuguese and Spanish writings, “Guinea” meant Upper Guinea. Early Portuguese documents and chronicles called the Gold Coast, the Slave Coast, and the Bights of Benin, and Biafra the Mina Coast. In the writings of Alonso de Sandoval, “Guineas” meant Greater Senegambias. As late as the nineteenth century, “Guinea” continued to mean Upper Guinea to other Atlantic slave traders as well. When King James I chartered the first English company to trade with Africa in the early seventeenth century, the Portuguese and Spanish usage of the term “Guinea” was initially adopted. The English company was named the Company of Adventurers, and it was to trade specifically with “‘Gynny and Bynny’ (Guinea and Benin).” After the northern European powers began to enter the Atlantic slave trade legally and systematically in the 1650’s, “Guinea” was gradually extended to mean the entire West African coast from Senegal down through Angola. . . .

After Portugal separated from Spain in 1640, Spanish Slave traders dominated at Cacheu in Greater Senegambia. Their undocumented voyages paid no taxes to Portugal. We only know about them because they appear in documents in the form of unsuccessful Portuguese efforts to repress them.

By the mid-seventeenth century, Africans and their descendants in the Caribbean began to outnumber whites very substantially. This demographic imbalance escalated during the eighteenth century. Because of their reputation as rebels, Greater Senegambians became less welcome. Although Greater Senegambians were feared in Spanish colonies, they were readily accepted - if not preferred - in the colonies eventually incorporated in the United States, where black/white ratios were much more manageable and therefore security problems did not loom as large. The Greater Senegambians’ skills were especially needed in rice and indigo production and in the cattle industries of Carolina, Georgia, the Florida panhandle, and Louisiana. During the eighteenth century, Greater Senegambians were more clustered in colonies that became part of the United States than anywhere else in the Americas. These colonial regions include the Carolinas, Georgia, Louisiana, the lower Mississippi Valley, and the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico extending across Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, the Florida panhandle, and, to a lesser extent, Maryland and Virginia. The Stono Rebellion of 1739 has focused attention on West Central Africa as a source for enslaved Africans brought to South Carolina. But a majority of Atlantic slave trade voyages arrived in South Carolina from West Central Africa during only one decade: between 1730 and 1739. The Stono Rebellion of 1739, well described as a Kongo revolt, evidently discouraged South Carolina planters from bringing in more West Central Africans. Thereafter, Greater Senegambia became the major source of Atlantic slave trade voyages for the rest of the eighteenth century. But the number of slaves on voyages arriving from Greater Senegambia was substantially smaller than on voyages arriving from other African regions. West Central Africa did not become a significant source of Africans for South Carolina again until 1802: only six years before the foreign slave trade to the United States was outlawed on January 1, 1808. From the study of transatlantic slave trade voyages, it appears that during the eighteenth century the United States was the most important place where Greater Senegambians were clustered after the northern European powers legally entered the Atlantic slave trade. [Siphiwe note: thus, two issues arise - 1) what was the “illegal” slave trade; and 2) how did the slave trade become “legal” - serious scholars pursuing reparations who can show that their ancestors were enslaved in the “illegal” slave trade have a special kind of legal argument; #2 can be contested - whose law? Certainly it was not any law of the Balanta, for example, that made slavery “legal” because ALL historians have documented that the BALANTA did not enslave people or participate in the transatlantic slave trade - so how do conflicts between competing international legal jurisdiction get resolved?]

Studies of transatlantic slave trade voyages to the United States are reasonably revealing about trends in ethnic composition because there was no large-scale, maritime transshipment trade to colonies of other nations. This conclusion must be qualified because of the unknown, and probably unknowable, extent and ethnic composition of new Africans transshipped from the Caribbean to the east coast ports of the United States. But it is likely that Greater Senegambians were quite significant in this traffic because of selectivity in the transshipment trade from the Caribbean. From the point of view of African ethnicities arriving in South Carolina, the artificial separation between Senegambia and Sierra Leone obscures the picture. Thus the role of Greater Senegambians was very important in South Carolina. There is evidence that Senegambians were clustered regionally in the Chesapeake and probably elsewhere as well, especially on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina and other rice-growing areas of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. The patterns for Louisiana are clear and not at all speculative. Greater Senegambians loomed large among African there. In the French slave trade to Louisiana, 64.3 percent of the Africans arriving on clearly documented French Atlantic slave trade voyages came from Senegambia narrowly defined. Based on The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database for British voyages to the entire northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico as well as additional Atlantic slave voyages found in Louisiana documents that were included in the Louisiana Slave Database but not in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, this writer’s studies show that slave trade voyages coming from Senegambia were 59.7 percent of all documented voyages coming directly from Africa to Louisiana and the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico between 1770 and 1803. . . .

In the two major rice-growing states of the Anglo-United states, 44.4 percent of Atlantic slave trade voyages arriving in South Carolina and 62 percent arriving in Georgia listed in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database brought Africans from Greater Senegambia. These gross, static figures are impressive enough. But when we break down calculations for Anglo-United States colonies and states over time and place, we see a wave pattern clustering Africans from Greater Senegambia.

In South Carolina, 50.4 percent of all Atlantic slave trade voyages to that colony entered into The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database arrived between 1751 and 1775, with 100 (35.2 percent) coming from Senegambia and 58 (20.4 percent) coming from Sierra Leone: a total of 55.6 percent coming from Greater Senegambia.

As we have seen, both Mandingo and Fulbe were being exported from both of these regions. During this time period, Britain had occupied the French slave-trading posts along the coast of Senegambia. Close to half (44.7 percent) of the British Atlantic slave trade voyages from Senegambia (narrowly defined: excluding Sierra Leone) went to Britain’s North American mainland colonies. Five out of six Atlantic slave trade voyages to British West Florida ports along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico came from Senegambia narrowly defined.

It is safe to say that between 1751 and 1775, the majority of slaves loaded aboard British ships leaving from Senegambia were sent to regions that would become part of the United States.

As Yankee traders and Euro-African [Siphiwe note: mixed race mulatto children] took over the Atlantic slave trade on these coasts during the Age of Revolutions, voyages bringing Africans to the United States from Greater Senegambia originated mainly in various ports on the American side, were heavily involved in smuggling and piracy, were never documented in European archives, and were unlikely to be included in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. There is little doubt that most of these voyages brought Greater Senegambians to the United States and to the British Caribbean.

Although the Igbo from the Bight of Biafra loomed large in the Chesapeake, Greater Senegambia was a formative culture in some regions of the Chesapeake as well. Lorena Walsh has noted that nearly half of the voyages bringing about 5,000 Africans to Virginia between 1683 and 1721 came from Senegambia narrowly defined. There was a clustering of Atlantic slave trade voyages from the same African coasts to regional ports in the Chesapeake.

In sum, The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database is probably less useful for Greater Senegambia than for any other African region except perhaps for West Central Africa. . . . Thus there are a comparatively small number of transatlantic slave trade voyages from Greater Senegambia because in many instances the point of origin was improperly entered. As we have noted before, the database defines the African coast recorded in documents as “Guinea” or the “Rivers of Guinea” as an unknown African coastal origin, writing the mistake into cybernetic stone. These voyages are lumped indistinguishably with unidentified African coasts and cannot be dis-aggregated for calculations. . . .

Many of the two-way voyages between North America and Africa were undocumented. Documents for other voyages are probably scattered among surviving documents in ports throughout the Americas.

We have seen that there is evidence for ongoing, direct trade involving American slave owners/traders/ship owners, often-overlapping categories, and Euro-African merchants [Siphiwe note: mixed race mulatto children] in Greater Senegambia. These small voyages were probably numerous and undocumented. Enslaved Africans were purchased directly by slave owners for their own use rather than for resale in the Americas. These slaves therefore do not show up in European or American sources, either in lists of incoming ships, advertisements for the sale of newly arriving slaves, or documents involving sale of slaves.

The large, centralized European archives documenting large, commercial voyages are very unlikely to contain documents involving privately organized voyages initiated in the Americas. Before the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Afro Portuguese [Siphiwe note: mixed race mulatto children] and Yankee traders and smugglers had taken over the slave trade along the coast south of the Gambia River. Jean Gabriel Pelletan, director of the French Company of Senegal in 1787-88, wrote that French slave trade ships rarely stopped between the Gambia and the Sierra Leone rivers because Afro-Portuguese [Siphiwe note: mixed raced mulatto children] drove their rivals away by force. After the French Revolution began in 1789, these invisible voyages from Greater Senegambia increased sharply. By 1794, Yankee traders had seized control of the maritime slave trade from the French and set up trading stations, although a few voyages were organized by French slave traders under neutral flags. After 1808, when Britain outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, British anti-slave trade patrols began operation along the West Coast of Africa above the equator. Warfare among the major European powers brought the open, large-scale, commercial Atlantic slave trade in Greater Senegambia to a halt.”

BALANTAS TAKEN FROM THE SOUTHERN RIVERS AREA

Finally, it should be noted that In the 1750’s Merchants of Grao Para and Maranhao (Brazil) call for an increase in its slave imports from Guinea for sugar, cotton, rice and cacao production and are authorized by the Crown to form a slave trading and commercial company. In an excerpt taken from Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade by Boubacar Barry writes:

“Walter Rodney gives estimates of slaves shipped in the Southern Rivers area, which remained the main market for British, French and Portuguese slave traders operating in Senegambia. From 1754 on, Bissau and Cacheu became the principal entrepots for the large-scale export of slaves, fed by the revival of manhunts and warfare in the hinterland. In 1789, the Southern Rivers easily exported over 4,000 slaves. In 1788, French navel intelligence reports estimated the number of slaves exported by the British at 3,000 from Gambia, 2,000 from Casamance, Cacheu, and Bissau, and 4,000 from Sierra Leone.

The critical evaluation conducted by Jean Mettas on Portuguese commerce at Bissau and Cacheu between 1758 and 1797, under the near-total monopoly of the Companhia General do Grao Para e Maranhao, gives a good idea of Senegambia’s contribution to the development of certain parts of Brazil. The turnover of slaving vessels owned by the C.G.G.P.M. at Cacheu and Bissau was exceptionally rapid. Between 1756 and 1778, the total number of voyages was as high as 105. Jean Mettas estimates that the Portuguese shipped an annual average of 420 captives from Cacheu between 1758 and 1777, while Bissau, more open to the inflow of French or British slavers, shipped an annual average of 620 slaves from 1767 to 1773. It is a remarkable fact that in the second half of the eighteenth century the number of slaves exported averaged slightly over 1,000 per year. The uninterrupted drain caused by Portuguese traders was particularly devastating for the inhabitants of the Southern Rivers: the Balanta, Bijago, Joola, Manjak, Bainuk, Papel, Nalu, Beafada, and, to a lesser extent Manding and Peul from the hinterland. The Portuguese monopoly belonged to the C.G.G.P.M., a chartered company whose slaving business was part of a vast enterprise of interconnected activities in Portugal and Brazil. Its profits were impressive: starting with a capital base of 465,600,000 reis, the company succeeded in paying out 17,396,600 reis to its shareholders between 1759 and 1777, with a rate of profit running at 11.50 percent from 1768 to 1774.”

When the American Revolutionary War begins, Americans increase imports of rice and cotton from Maranhao, which requires more slaves from Guinea. Historian Walter Hawthorne writes,

“by 1755 the unregulated trade in slaves from Bissau was booming. That year, Portuguese officials in Cacheu reported that Portuguese and French ships were leaving the island with ‘substantial cargoes of captives.’ The Company of Grao Para e Maranhao, which was accorded monopoly trading privileges for the Guinea -Bissau region beginning in 1755. The company had been created to supply the Brazilian states of Par and Maranhao with slave laborers. By 1775 the company had completed a fort, the Praca de Jose de Bissau. The fort had strong 40-foot-high stone walls that formed a square, at the corners of which were four bulwarks. Trenches surrounded all of this. And the company had an enormous holding pen for slaves. Like the Portuguese government had on many occasions before, the Company of Grao Para e Maranhao sought to undercut the power of Luso African traders who lived in the region. The company was especially keen on defending its monopoly trading rights, and it feared Luso Africans would not recognize these. With British vessels regularly purchasing slaves in Bissau and Geba from ‘Portuguese’ in the 1760’s, the company’s fears were well grounded.”

APPLYING THE ABOVE TO GENEALOGY RESEARCH: BALEKA FAMILY CASE STUDY

From the above, we learn that:

Since 1640, slave traders began an undocumented, illegal slave trade from the port of Cacheu to avoid paying taxes to Portugal.

Between 1751 and 1775, the majority of slaves loaded aboard British ships leaving from Senegambia were sent to regions that would become part of the United States.

In South Carolina, 50.4 percent of all Atlantic slave trade voyages to that colony entered into The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database arrived between 1751 and 1775, with 100 (35.2 percent) coming from Senegambia.

Voyages bringing Africans to the United States from Greater Senegambia originated mainly in various ports on the American side, were heavily involved in smuggling and piracy, were never documented in European archives, and were unlikely to be included in The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

Many of the two-way voyages between North America and Africa were undocumented.

There is evidence for ongoing, direct trade involving American slave owners/traders/ship owners, often-overlapping categories, and Euro-African merchants in Greater Senegambia. These small voyages were probably numerous and undocumented. Enslaved Africans were purchased directly by slave owners for their own use rather than for resale in the Americas. These slaves therefore do not show up in European or American sources, either in lists of incoming ships, advertisements for the sale of newly arriving slaves, or documents involving sale of slaves.

90% of the documented slave voyages from the Balanta homelands near the ports of Cacheu and Bissau were by The Company of Grao Para e Maranhao (C.G.P.M.). However, most of their voyages went to Brazil and the Caribbean, not directly to the British North American colonies.

C.G.P.M. did have a commercial network with the American colonies importing rice and cotton.

Thus, if you have an English name and your ancestor is Balanta, it is most likely that your ancestor came to America either through a commercial network incolving C.G.P.M. or arrived through illegal and undocumented British slave trading.

Now consider, this example. The North Carolina Wills and Probate Records, 1819 for “Demsey Blake”, show that he bequeathed to his son Asa Blake his “negro man Jack” who happens to be my great, great, great, great grandfather. That same year, 1819, Jack had a son called Yancey, my great, great, great grandfather. The North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records of 1850 states, “I, Asa Blake of the County of Wake and State of North Carolina . . . I leave to my well beloved wife Siddy (or Ciddy or Liddy) Blake . . . the following negroes (to wit) a negro man Jack, +Yancy, and also a negro woman [S]ealy and Matilda . . .” Meanwhile, the North Carolina Marriage Records show that Jack was emancipated and married Cherry Blake on October 10, 1853. Now Jack’s father was Brassa Nchabra, who was captured as a young boy from his homeland in Nhacra, just east of the slave ports of Cacheu and Bissau, and brought to Charleston South Carolina sometime between 1758 and 1775. There is no record, however, listing Brassa Nchabra, who was given the English name “George” after the despicable slave holder George Washington. How did Brassa Nchabra arrive in Charleston, South Carolina? We may never have definitive proof because it is likely he was brought by the prominent slave-holding Blake family.

Dempsey Blake was born in 1757 in Wake County, North Carolina were my great, great, great grandfather Yancey Blake was born in 1819. Dempsey Blake’s great, great grandfather was Admiral Robert Blake. According to the book Southern Blakes by Kate Blake,

“Sir Robert Blake was born in 1599 in Bridgwater, Somerset, England and died in 1657. He became famous in the War with Holland. When Civil War raged in England between Parliament and Charles the First, his naval forces destroyed the Squadron of Prince Rupert, the Royalist General. For this he was made Commander-in-Chief of the English Fleet. He won four victories over the Dutch Admiral, Martin Tromp, in 1652 and 1653, resulting in England becoming Mistress of the Seas.

Blake was sent by Cromwell to the Mediterranean Sea in 1654 to avenge British insults to the British Flag and near Tunis he attacked and destroyed a fortified harbor. Tunis and Algiers made terms at once, releasing all prisoners and paying an indemnity.

Blake also made a bold attack on the Spanish Fleet at Santa Cruz in the Canary Islands. He seized booty amounting to $14,000,000. He died of scurvy on his way home, while in sight of Plymouth (1657). Sir Robert was knighted for his services in 1654. Sir Robert’s younger brother settled in what is now South Carolina.

Thomas Blake {Dempsey Blake’s great grandfather] was the grandson of Sir Robert Blake and the son of one of the two sons of Sir Robert. . . . There is ample proof that Thomas Blake who settled in Isle of Wight County, Virginia, was a ship owner of considerable wealth. There is also proof that he was paid in land for the numerous indentured people he brought to Virginia Colony. He owned at least two ships, accumulated property in the new world and sometime around 1664, settled permanently in Isle of Wight.

Concerning Sir Robert’s younger brother that settled in South Carolina, in 1663, soon after his restoration to the English throne, Charles II granted eight Lords Proprietors – including Baron Berkeley of Stratton (1602–1678) - a huge tract of territory south of Virginia. The Lords Proprietors sought easy profits by renting lands and selling a wide variety of commodities. They recognized that a slave colony in Carolina held the greatest commercial promise. A group of colonists from Barbados wished to settle in Carolina and bring their slaves with them. They pressed the Lords Proprietors to establish a headright system under which the heads of all households would be allotted acreage on the basis of the number of people who accompanied them. The proprietors assented by granting ‘the Owner of every Negro-Man or Slave, brought thither to settle within the first year, twenty acres, and for every Woman Negro or Slave five acres.’

The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine Vol. 1, No. 2 (April, 1900), pp. 153-166 states,

“This distinguished Carolina family is descended, as Oldmixon tells us, from a brother of Admiral Blake. In his History of the British Empire in America, Oldmixon writes, ‘I say more of Mr. Blake because his family is one of the most considerable in this Province; where he arrived in the year 1683, with several other Families the followers of his fortune.’

[Footnotes 1 and 2 state] ‘T’was about this time, that the Persecution raise’d by the Popish Faction, and their adherents, in England, against the Protestant Dissenters, was at its height; and no Part of this Kingdom suffer’d more by it than Somersetshire. The Author of this History liv’d at that time with Mr. Blake, brother to the famous General of that name being educated by his Son-in-law, who taught School in Bridgewater: and remembers, tho’ then very young, the reasons old Mr. Blake us’d to give for leaving England: One of which was, That the miseries they endur’d, meaning the Dissenters then, were nothing to what he foresaw would attend the Reign of a Popish successor; wherefore he resolv’d to remove to Carolina: and he had so great an Interest among Persons of his principles, I mean Dissenters, that many honest substantial Persons engaged to go over with him. [Oldmixon, Car. Col: 2 p. 407].

Warrant to Maj: Maurice Matthews: To lay out to Capt: Benjamin Blake 1090 acres of land in some place not yet laid out &c the said land being due to the said Benjamin Blake by and for the transportation into this province of himself and 21 persons whose names are recorded in the Secretarys Office in the said province &c 10 May 1682 &c Dated 18 March 1683. Joseph Morton &c Sec: Office Bk 1682-92 p 243. This was probably Pawlets; The grant to Plainsfield, 1000 acres was 5 July 1683.’

What estate he sold in England he sold to carry the effects along with him . . . .

Benjamin Blake of Plainsfield and Pawlets, Esq: J.P, Lords Proprietors Deputy and Member of the Grand Council of Carolina, Gov: Archdale in his Descriptions of Carolina says: ‘In Gov: Moretons time General Blake’s Brother with many Dissenters, came to Carolina, which Blake being a wise and prudent person of an heroic temper of spirit, strengthened the hands of sober inclin’d people and kept under the first loose and extravagant spirit, &c. The Governor, as we are told marry’d Mrs. Elizabeth Blake his daughter, and by this alliance the strength of their party was so increas’d that we hear little of the other till Mr. Colleton’s government.’ Capt. Blake received considerable grants of land in the province and settled the large plantations of Plainsfield and Pawlets in Colleton County. About the year 1685 he was appointed Lords Proprietors deputy and in October of that year signed the new constitutions and oath of allegiance to King James.

He served in the Council during the administration of Gov Moreton and Colleton: the Lords Proprietors recommended him ‘as a confidential man’ and appointed him Clerk of the Crown and Peace for S. Carolina. In 1686 he was commissioner under the act for public defence and in 1687 one of the committees to revise the constitutions which drew up a new form of government for the province. Capt. Blake died about the year 1689 and was succeeded by his son:

Right Hon Colonel Joseph Blake of Plainsfield and Pawlets, Esp: S.P., Landgrave of Carolina, one of the true and absolute Lords and Proprietors of Carolina (after the Crown purchased the proprietors' interests in 1729 and transferred Baron Berkely’s proprietorship to Joseph Blake) and twice Governor of South Carolina. Was born and educated in England. He probably followed his father to Carolina and on his death was appointed Lords Proprietors deputy in his stead but was removed by Gov. Sothell, Oct. 1690. The Proprietors remonstrated and reappointed Blake to Gov. Ludwells council, Nov 1691. He served in Gov Ludwells and Smiths councils and on Gov: Smith’s resignation, Oct. 1694, succeeded him as Governor of the province and was created a Landgrave. Col. Blake provided for defence of the province ‘in these times of War with the French King’ and served as governor until Gov. Archdale’s arrival in 1695 and then as deputy in his new council. . . . Gov: Blake inherited a good estate, received large grants of land himself and acquired a considerable property. . . . Gov: Blake died 7th September 1700 and was succeeded by his only son: Hon Colonel Joseph Blake.

He was born in 1700 and educated probably partly in England. . . . Col. Blake inherited his father’s Proprietorship and landed estates, besides a good estate from his mother’s family including the Newington, Mt Boone and Cypress lands, some 6000 acres, and the fine Newington mansion, where he chiefly resided. His Proprietorship was surrendered to the King under Act of Parliament 1729. . . .

William Blake (2nd son of Hon: Joseph Blake) of Plainsfield and Pawlets . . . . was born at Newington in 1739 and educated in England. He received a large fortune from his father and acquired considerable estates in England and Carolina. . . .

According to SLAVEHOLDERS FROM 1860 SLAVE CENSUS SCHEDULES transcribed by Tom Blake, the following descendants of the South Carolina Blakes would become some of the biggest slave holders

JOSEPH BLAKE, at SC, Beaufort, roll 1231, page 89 of Prince William Parish, holding 575 slaves

ARTHUR BLAKE, at SC, Charleston, roll 1232, page 307B, holding 538 slaves.

DANIEL BLAKE, at SC, Colleton, roll 1234 page 103 of St. Bartholomew, holding 527 slaves.

BLAKE Beaufort Co., SC

BLAKE, Colleton Co., SC

BLAKE, Holmes Co., MS

BLAKE, King William Co., VA

BLAKE, Leon Co., FL

BLAKE, Warren Co., MS

Returning to the book Southern Blakes by Kate Blake,

“On April 10th, 1704, the above said Thomas, for love and natural affection as a consideration, deeded 100 acres to his son, William Blake, both then being of the Upper Parish of said County, Isle of Wight, Va. . . . For about the time Thomas gave William a deed for 100 acres, Nicholas Sessums gave a similar deed for a 100 acres to his daughter, Mary Blake, and his son-in-law William Blake; and I am of the opinion that these deeds were marriage gifts. . . . Nicholas Sessums was a man of much property, owned 1000 acres of land, numerous slaves . . . .

Now the Blakes, William Sr. and William Jr. – father and son – held the tract of land on Walnut Creek near Raleigh, for a period of nearly thirty years; 14 years while it was in old Johnston County, and the remainder of that period while it was in Wake County.

William Jr. received a grant of land 1730; and in 1735 he sold it to Joshua Claude; and he went to North Carolina and received a grant of land in Edgecombe County, 1744 – which land was actually located in what is now Warren County. . . . This William received a grant of land in old Edgecombe County, N.C., 1744, . . . Moreover, Edgecombe County, as of that date, was a small empire- 19 counties having been created from it in later days. Thus, it would be hard to determine just where this 1744 grant was actually located – but as a guess, I would say that it was in what later became Bute, County, and still later Warren County, N.C., land located on North Side of Fishing Creek. Our next record of the said William No. 2, was found in Granville County, which county was set off from Edgecombe, 1746. He purchased a tract of 250 acres from one George Rollison, both parties of Granville County, April 17th, 1750, and paid for it with Virginia money; said tract of land being half of a grant of 500 acres to John Alston, North Side of Fishing Creek. . . . John Pullen, the party to whom William (No. 3) and Lucy Blake sold, just before they set out for Georgia, sold both the William Blake (no.2) tract and John Blake tract, to Co. Theophilus Hunter – one of the great early characters of both Johnston County and Wake County.”

William Blake Sr. had a son, Joseph B. Blake, who was born in 1727 in the Isle of Wight, Isle of Wight County, Virginia and died in Wake County, North Carolina on August 19, 1771 at the age of 44.

William Blake Sr.’s will was probated in 1746 and gave lands to four of his children, including Joseph Blake, whose son Dempsey Blake was born in 1757 in Wake, North Carolina (mother is Elizabeth Hobsgood). Dempsey had brothers named Asa Blake and Sessums Blake. Dempsey married Susannah Sorrell and fathered Anna Blake, Patsey Massey, Asa Blake, Betsy Blake, and Mary Page. Joseph Blake died in 1771 in Wake County. According to Wake County Records, Dempsey Blake was granted 552 acres on both sides of Crabtree Creek in 1779.

Dempsey Blake is listed in the 1790 Census for Wake County, North Carolinas owning 7 slaves.

In 1797 Dempsey Blake bought from the estate of John Jones and William Brown. Asa Blake (Dempsey’s brother) also purchased from William Brown’s estate. In 1799, Dempsey purchased from the estate of Theophilus Hunter (see 18 above) and in 1800 he purchased from the estate of James “Waldrope” (in another source, he is James Wardrope).

According to the North Carolina Wills and Probate Records, 1819 for “Demsey Blake”, he bequeathed to his son Asa Blake his “negro man Jack”. That same year, Jack had a son named Yancey Blake.

So we can see from this history that Dempsey Blake belonged to an infamous family of private slave traders who got their start from their mercenary pirate ancestor, Robert Blake, who made the family fortune by robbing Spanish ships off the coast of West Africa. Given Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s research excerpted above, the Blake family is exactly the kind of people who engaged in the illegal British slave trade that brought slaves to Charleston, South Carolina and Chesapeake, Virginia. Thus, it is unlikely that I will be able to find any record documenting the capture and transport of Brassa Nchabra to Charleston, SC.

Finally, the lack of records, however, indicates that such trading, including that of my great, great, great, great, great grandfather was illegal. And this is ground for a new kind of reparations case claiming that the enslavement of people through such channels was considered illegal by the European and American laws at the time. The case could not have been made in the 1760’s by Brassa Nchabra as a young boy that could not speak English, but the case can certainly be made now.