From Nationalism, Referendums and Democracy: Voting on Ethnic Issues and Independence, Second Edition edited by Matt Qvortrup

“Establishing a new state is a major political, legal and economic undertaking. Before considering the practicalities of such an endeavour, and the likely economic implications of it, it is necessary to outline some of the other examples for countries that gained their independence/seceded from other countries.

In the twentieth century, a large number for former colonies gained independence, and a good number of countries that hitherto were part of larger states seceded. While there were examples of this before the Second World War, for example, when the Philippines became independent in 1935, most new states were established after the Second World War. In this period, most of the new states were former colonies, for example, the former British Colonies, India, Kenya and the former French colonies Senegal, Togo and Cameroon.

By contrast, after the Cold War, most newly established countries were not former colonies but were areas which hitherto had been part of larger entities, for example, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina in Former Yugoslavia, and Ukraine and Belarus, to name but two, which were previously part of the Soviet Union.

“The problem with these referendums is not only that they have occasionally – though not generally – resulted in war. The problem is also that many would-be states claim to have a right to self-determination, that they consider it legally right – and not just morally just – that they have a right to declare independence after a referendum. As the examples of Catalonia in 2017 and Kurdistan in the same year show, this belief is widespread, but it is based on legally dubious grounds. This duality is the subject of Peter Radan’s chapter. Surveying the legal practice from the American Civil War (which was predated by referendums on independence in several confederate states in the South), the author looks at the emerging legal doctrine surrounding independence referendums. While he acknowledges that a decisive vote may have moral force, his admirably dispassionate analysis is equally clear that there is no right to hold an independence referendum. Such votes, he shows, can only be held where there are constitutional provisions that allow them, following a peace deal or in cases where the territory in question is a former colony.

As a general rule, unilateral referendums on independence are only legally permissible in cases where the people in question have no other recourse through democratic means. Thus, the referendum in Kurdistan could conceivably be regarded as legally permissible, as Iraq is not a democratic state (as defined by Freedom House). Conversely, the Catalan referendum (notwithstanding unnecessary show of force by the Spanish Police) was not justified, as Spain is a democratic state.

It was one of the more spectacular moments in recent history, when President Carles Puigdemont issued his Declaració d’independència de Catalunya – the declaration of independence of Catalonia. It happened on the 1 October 2017, a couple of weeks after a majority of over 90% of the voters – on a less than 50% turnout – had voted for independence.

The declaration came to naught. Puigdemont’s political comrades were jailed, and he escaped to Belgium. The Spanish government dealt resolutely (some would say harshly) with, what they considered to be, an insurrection. But the Catalan crisis was not common. Indeed, the fact that it was peaceful makes it stand out. As Aleksandar Pavković writes, most declarations of independence in recent decades were made prior to military interventions by outside states which led to the eventual independence of these states. And all of these declarations, except the first three declarations in Kosovo, were made during or following the violent conflict on the territory whose independence is being proclaimed.

The fact that the Catalan Declaració failed might be explained by the fact that the territory was not supported by a strong, foreign, military power. Contrast this with declarations of independence in states with more dubious claims, such as South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and it is clear that power politics plays a stronger role than reference to ideals in international affairs.

It is one thing to declare independence, but it is quite another to be recognised. . . . But it might be useful to point out that recognition is now part of a legal process. In summary, this goes as follows: First, the state submits an application to the United Nations Secretary-General and a letter formally stating that it accepts the obligations under the UN Charter. Secondly, the Security Council considers the application. Any recommendation for admission must receive the affirmative votes of 9 of the 15 members of the Council, provided that none of its five permanent members – China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America – have voted against the application. Thirdly, if the Security Council recommends admission, the recommendation is presented to the General Assembly for consideration. And, finally, if membership is supported by a two-thirds majority in the General Assembly, the state in question is granted immediate membership.

In short, creating a new state is no easy task. Holding a referendum (sometimes of dubious legality), winning a majority in favour of independence, declaring independence and getting recognition, all of these steps require almost superhuman efforts. The benefits seem meagre. And yet, history has shown that the quest for national self-determination is one of the strongest urges in international politics. . . .

Ethno-national referendums after the fall of communism

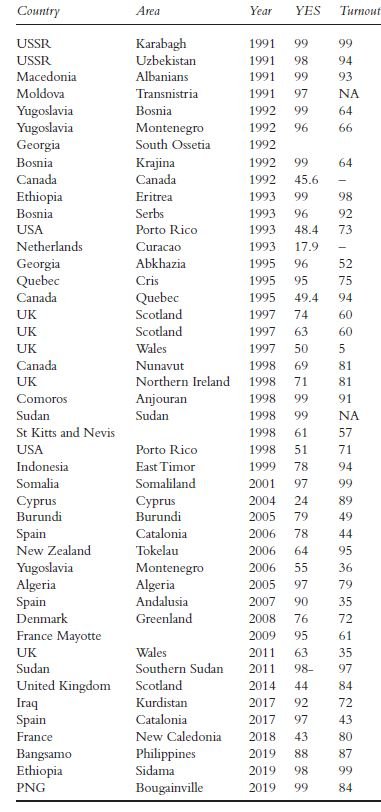

There have been 114 ethno-national referendums since the Second World War. Sixty seven were held after 1989 and of these 35 of these were held between 1989 and 1993, and were all and more or less direct consequence of the fall of communism. That such momentous events shake the political kaleidoscope is not surprising, nor, perhaps, is it surprising that the developments left their mark on legal practice. There is a bit of a sea change in the new doctrine adopted after 1989. As Matthew Craven has observed, ‘Of the new states that were to emerge in the 1990s … most held plebiscites or national polls by way of authorization’ (Craven 2010: 234). It became a norm in international law that countries ought to win approval from the people in order to be recognised as an independent state, and it became recognised – at least in democratic states – that policies of difference management required positive approval from the citizens concerned.

As we can see from Table 2.8, most of the referendums held post-1989 were held in former communist countries. And 31 of the 66 votes were held in countries that were formerly ruled by one-party communist regimes, such as Eritrea (then part of Ethiopia), Ukraine, the Baltic States and various successor states in the former Yugoslavia. Yet other ethno-national referendums were – at least indirectly – a consequence of the end of the Cold War. The nationalist aspirations of the population of East Timor were well known before the fall of communism, but for geo-political reasons, the United States supported Suharto’s regime. Once the threat from the Soviet Union was gone, the USA loosened its grip and accepted (and some would even say encouraged) the fall of the autocracy, and as a result East Timor was allowed to vote on independence in 1999 (Steele 2002).

Another interesting factor is that referendums in democratic countries (here defined at ‘Free’ following the Freedom House classification) rarely vote for independence. After the 1995 vote in Quebec, a political scientist (who later became a leader of the Liberal Party!) wrote,

“There has never been a single case of secession in democracies if we consider only the well-established ones, that is, those with at least ten consecutive years of universal suffrage. The cases most often mentioned happened only a few years after the introduction or significant expansion of universal suffrage: Norway and Sweden in 1905, Iceland and Denmark in 1918, … Secessionists never managed to split a well-established democracy through a referendum or an electoral victory. We must conclude that it is very hard for them to achieve and maintain the magic number of 50 per cent support (Dion 1996: 269).”

20 MARCH 1921: UPPER SILESIAN PLEBISCITE (POLAND V GERMANY)

13 JANUARY 1935: THE SAAR PLEBISCITE TO REUNITE WITH GERMANY

1947 SYLHET PLEBISCITE (PAKISTAN)

6 JULY 1948 -THE KASHMIR PLEBISCITE THAT NEVER HAPPENED

1961 - SOUTHERN CAMEROONS PLEBISCITE

1986: PALAU PLEBISCITE

5 OCTOBER 1988 - CHILE - PINOCHET LOSES HIS OWN PLEBISCITE

BANGSAMORA PLEBISCITE

New Caledonia - December 2021

An independence referendum was held in New Caledonia on 4 October 2020. The poll was the second to be held under the terms of the Nouméa Accord, following a similar referendum in 2018.

Independence was rejected, with 53.26 percent of voters opposing such a change, a slight drop from the 2018 result in which 56.7 percent voted "no". Turnout was 85.69 percent. The Nouméa Accord permitted one further referendum to be held, should the Congress of New Caledonia vote for it. This third referendum was held in December 2021.

With a turnout of 85.6 percent, 53.26 percent of voters opted for "no", with the result that the islands remain French. This was a lower figure than the 2018 poll, in which 56.7 percent voted "no".[9] Results were strongly polarised geographically, with 71 percent of South Province residents rejecting independence, while the smaller other two provinces, North Province and Loyalty Islands Province, voted "yes" by 76 percent and 82 percent respectively.[27] In almost every commune, the share of "yes" votes increased.

As this was the second of three permitted independence referenda, it was expected that there may be a third and final referendum at some point before 2022.[9] Daniel Goa, of the pro-independence party Caledonian Union, expressed a hope that the shift in vote share towards the "yes" camp would lead to a successful third referendum. Meanwhile Sonia Backès, leader of Les Loyalistes, called for dialogue between the two sides although she acknowledged that it might be necessary to hold the third referendum before such a dialogue could commence.[28]

French president Emmanuel Macron expressed gratitude for the result, thanking New Caledonians for their "vote of confidence" in the Republic. He also acknowledged those who had backed independence, calling for dialogue between all sides to map out the future of the region.[27]

In April 2021, 26 pro-independence members of Congress requested that a third vote take place. On 2 June, the French government announced that the third referendum was scheduled for 12 December 2021. [29] This third referendum resulted in an overwhelming rejection of independence, with 96.49% of the electorate voting against independence and 3.51% for independence. However, turnout was significantly lower than in past referendums at only 43.90%.[2]