In 2025, I have served as the Afrodescedants’ Special Envoy to Burkina Faso and have attended two delegations in July and August. However, I confess I know little about the jihadists in the Sahel Region that is creating so much problems. Today, I asked, “Who are these people, what are they doing, and why?”

Here’s what I am learning.

ESTABLISHING THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF AZAWAD IN WHAT IS NOW NORTHERN MALI

The object of the jihadist activity is to establish the independent state of Azawad under Sharia law in what is now Northern Mali. This became the priority after US President Barak Obama assasinated Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. See: Gold and Oil: Petrodollars and the United States Attacks in Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Mali, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Iran; Understanding Obama’s AFRICOM Betrayal of African People

The Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen, JNIM)

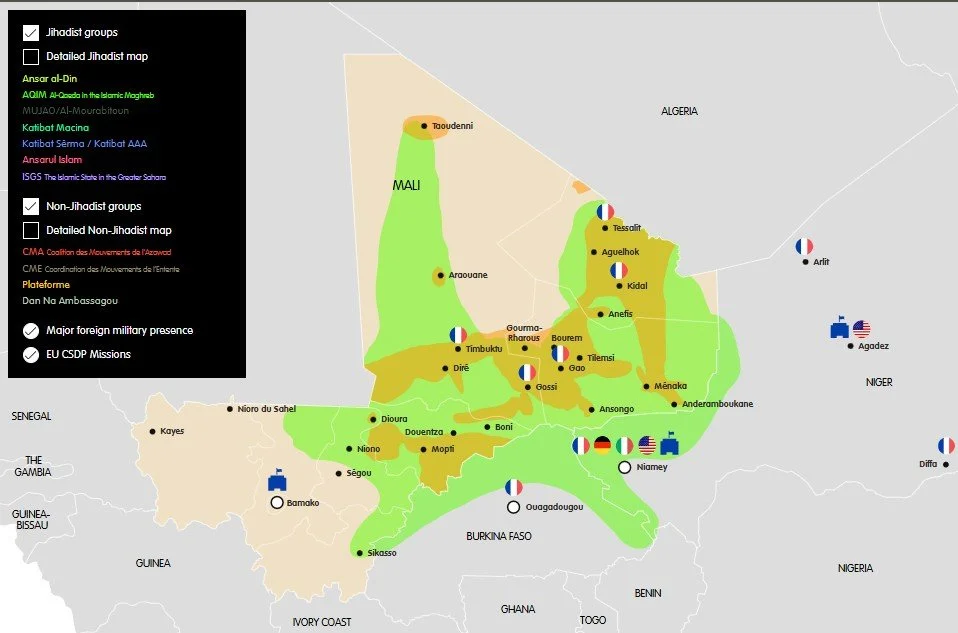

According to the European Council of Foreign Relations website Mapping armed groups in Mali and the Sahel,

“JNIM, an umbrella coalition of al-Qaeda-aligned groups, announced its existence in March 2017 in a video release featuring the leaders of its component parts – Ansar al-Din, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al-Mourabitoun, and Katibat Macina. Headed by Tuareg militant leader Iyad Ag Ghali, JNIM has since established an independent media arm and regularly claims responsibility for attacks throughout Mali. It took credit for the January 2019 attack that killed ten UN peacekeepers in Aguelhoc, recent devastating attacks on Malian army bases in Dioura and Guiré, and several attacks against security forces as well as other armed groups in Niger and Burkina Faso.

Broadly speaking, JNIM’s aim is to drive foreign (especially French and UN) forces out of Mali, and to impose its version of Islamic law. It maintains its allegiance to al-Qaeda and seeks to spread the reach of jihadist groups in the region. Although the components within JNIM act relatively autonomously, they have still consistently reaffirmed their membership in the umbrella group. Katibat Macina leader Amadou Kouffa in particular has consistently confirmed the centrality of Iyad Ag Ghali to the movement and to any potential negotiations with them. Despite heavy losses at the hands of French forces, JNIM continues to operate throughout Mali and into Burkina Faso and Niger, conducting complex attacks, assassinations, and improvised explosive device (IED) attacks on UN, Malian, and French forces.”

Detailed jihadist map https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping/jnim

THIS BEGS THE QUESTION DERIVED FROM THE PROVERB, “THE ENEMY OF MY ENEMY IS MY FRIEND”: WHAT OF THE COMMON INTERESTS BETWEEN THE JIHADISTS AND PAN AFRICANISTS VIS-A-VIS DRIVING OUT THE FOREIGN UN AND FRIENCH FORCES AND REMNANTS OF NEOCOLONIALISM VS THE ANTI-BLACK RACISM OF THEIR PAN-ARABISM?

Detailed non-JIhadist map https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping/jnim

Ansar al-Din

Iyad Ag Ghali, the central leader of the 1990 rebellion in Mali, formed Ansar al-Din in late 2011. The group quickly emerged around a core of Ifoghas Tuareg and longtime companions of Ag Ghali, eventually picking up support from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). It quickly emerged as an important military force during the rebellion. It has claimed responsibility for the attack at Aguelhoc in January 2012 where as many as 153 Malian soldiers were slaughtered. Ansar al-Din maintained a powerful position in collaboration with AQIM during the rapid push to take control of northern Mali. The group largely governed Kidal and was very present in Timbuktu alongside AQIM during the 2011 jihadist occupation. Operation Serval swept Ansar al-Din, along with its allies, out of northern Mali’s cities but it remained active. Kidal and its surrounding region, up to the border with Algeria, remained a centre of its activity. The group conducted and continues to conduct attacks against French, UN, and Malian forces before and since the creation of JNIM. While Ansar al-Din remains orientated around Kidal with a composition believed to largely be Tuareg and Ifoghas Kidal, it and Iyad Ag Ghali also played an important role in helping federate Mali and the region’s jihadist groups, leading to the formation of JNIM.

According to a 2012 article in the Guardian,

“The man pictured is Iyad Ag Ghaly – nicknamed "the strategist" – the Tuareg Islamist leader of Ansar Dine, the "defenders of the faith". It is this man's actions in the coming weeks that might determine whether there is a foreign-led intervention in Mali against him and his allies – al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao (the Movement for Openness and Jihad in West Africa).

Earlier this year it was the alliance of these three groups – Ansar Dine, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao – that captured large parts of Mali's north, including the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. Since then, they have imposed an unpopular and extreme interpretation of sharia law that has seen stonings, amputations and the destruction of shrines.

With the growing threat of an African Union-led intervention to retake the north, backed by the European Union and the US, the quixotic figure of Ag Ghaly has emerged as the focus of attempts to avoid a wider conflict by persuading him to swap sides.

Last week, as a delegation from the rival Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) was in Paris to press its case, it emerged that discussions are focusing increasingly on Ag Ghaly. It is perhaps not surprising, given his record. For while Ag Ghaly has worked hard to reinvent himself as a hardline Islamist leader, it was not always the case for a man long noted for his fondness for whisky and music. As a leaked US embassy cable suggested, Ag Ghaly has a reputation for self-interest, describing how he had long sought to "play both sides … to maximise his personal gain". . . .

The complicated tribal politics of northern Mali and the Sahel region have long set both rival tribes and competing social groups against each other. As the author of the leaked US cable in 2008 observed, what that meant in the 1990s was an "alphabet soup" of nationalist groups with different tribal attachments in an area the size of France, including, more recently, al-Qaida affiliates with financial interests in kidnapping and smuggling.

All that changed with the destabilising influence of the war in Libya that led to a flood of weapons into Mali, a military coup in the capital, Bamako, and the rebellion in the north, led first by the MNLA, a new group in which Ag Ghaly had sought a leadership role but had been rebuffed. The response of the quietly spoken tribal "aristocrat", say analysts, was to set up Ansar Dine as a rival group, forming an alliance of convenience with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao. It was a split that came to a head in March, when Ag Ghaly's rival rebels accused him of undermining the cause with his Islamist proclamations, calling him a "criminal" who wanted to found a "theocratic state".

In evidence to the US House foreign affairs committee earlier this year, Rudolph Atallah of the Atlantic Council, who has spent much time in northern Mali, said Ag Ghaly's split with other Tuareg leaders to found Ansar Dine meant Mali was "becoming a magnet for foreign fighters, who are flocking in to train recruits to use sophisticated weapons, built for and taken from [Muammar] Gaddafi's arsenal".

Ag Ghaly was born into a noble family in the Ifogha tribal group, who come from the Kidal region in the north. He travelled to Libya as a young man and joined Gaddafi's Islamic Legion, composed of exiles from the Sahel, whom Gaddafi used as cannon fodder in his conflict with Chad. He returned to Mali in 1990 to join the Tuareg uprising as a leader, later acting as a negotiator between the Malian government and the rebels.

His interest in the fundamentalist Salafist branch of Islam emerged, according to a profile in the French magazine L'Express, at the end of the 1990s, when he encountered Pakistani practitioners in Kidal at the same time as he was emerging as an intermediary for Islamist kidnappers, a profitable business from which he took a cut of the ransom. Ag Ghaly's contacts with the Islamists who would later form the core of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb were strengthened by the fact that a "cousin" was a leader of one of the groups.

Ag Ghaly also managed to maintain a working relationship with the former Malian president, Amadou Toumani Touré, persuading him to post him as the envoy to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, a closeness that was behind his rejection as a leader by rebels in the MNLA.

Now, however, Ag Ghaly is facing his greatest challenge. The lightning success of Islamist gains in Mali's north has gone down badly with many in the region. In a grand tour of the north to build support he was rebuffed by tribal leaders.

Other reports – impossible to verify – have suggested that even in his own fiefdom of Kidal his imposition of sharia law has proved deeply unpopular and he is running short of cash, while his group is suffering defections.

A UN security council resolution has authorised the formation of an African Union-led military expedition to recapture the north, while France, Germany and the US have offered logistical assistance. Algeria, which had been resisting any intervention, said that it would accept it as a "last resort" as long as it did not set foot on Algerian soil in hunting fighters.

Patrick Smith of the Africa Confidential newsletter, who was in Paris after the MNLA delegation, believes Ag Ghaly will be offered a choice. "There's a growing desire to reach out to him to say you can ally with us and help work out a deal for a decentralised north. If not, it's war and you'll end up on a list with other al-Qaida-associated leaders wondering when a drone is coming for you."

Listen to the lecture by Christopher Wise, Professor of English at Western Washington University (WWU), who gives an English language lecture on the Tuareg jihadist, Iyad Ag Ghali in the "Critical Nationalisms, Counterpublics" Lecture Series at Green College of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada on January 9, 2019. Wise's lecture provides a general overview of the 2012 crisis in Mali by focusing on Iyad Ag Ghali and his role in the conflict.

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

AQIM began as an outgrowth of the Algerian civil war. The group, formed in 1998 as the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), rejected the more violent and exclusivist tendencies of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) and particularly sought to focus instead on attacks against military and government targets. The GSPC also sought to expand its presence in the Sahara in search of opportunities to diversify its fundraising sources and find new areas of operation, training, and eventually recruitment. At first this effort was led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a former GIA member who had fought in Afghanistan and who was himself from a community of Saharan Arabs, the Chaânba. Officials claimed Belmokhtar was killed in an airstrike in Libya in 2016, though AQIM never publicly confirmed his death and regional intelligence sources claim he may still be alive.

The GSPC officially pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda in 2006 and became AQIM in early 2007. The GSPC and AQIM marked the first real transnational jihadist presence in the region, and they have sought through local relationships, basic governance, and military pressure to create durable space in which to operate and at times govern territory. Although AQIM has recruited widely and operated throughout the Sahel, they are strongest today in Mali, and are particularly strong in the regions of Kidal and Timbuktu.

The GSPC became a more entrenched presence in southern Algeria and northern Mali in particular, and its first kidnapping operations began in 2003. The GSPC also conducted its first attack in the region in Mauritania on the army base at Lemgeity in 2005. By early 2007, it was conducting attacks in Algeria while still implanting itself in the social fabric of northern Mali through marriage and business ties, as well as increasingly through local recruitment. Its kidnapping operations continued through the occupation of northern Mali and afterwards, accounting for a significant portion of the group’s financing despite persistent rumours that the group benefitted heavily from narcotics or cigarette smuggling.

Despite the split between AQIM and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) in October 2011, AQIM still played a significant role in governing northern Mali in 2012. It had a particularly strong presence in Timbuktu. Since Operation Serval, AQIM has reconstituted its units following a series of losses, including the death of Katibat Tarek Ibn Ziyad commander Abu Zeid in fighting with French and Chadian forces in 2013. It continued to conduct serious attacks against United Nations, French, and Malian forces up until the founding of JNIM, and maintained a strong presence then and subsequently in Timbuktu and to the city’s north, as well as from Anefis to Kidal and the Algerian border. AQIM has also conducted a series of attacks in Bamako as well as Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso under the auspices of al-Mourabitoun, which returned to the AQIM fold in 2015. AQIM has suffered significant losses recently, including the death of its Saharan emir and JNIM co-founder Yahya Abou el Hammam in a French operation north of Timbuktu. However, it still retains a significant presence particularly in the Timbuktu region, and maintains an ability to conduct operations.

Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO)/Al-Mourabitoun

MUJAO split from AQIM in October 2011, following accusations that AQIM was too dominated by Arab commanders and criticisms of its methods of jihad. From the beginning, MUJAO had a clearly Sahelian orientation, framing its fight in terms of historical jihads fought in the region in the nineteenth century and openly promoting its recruitment of Sahelian and sub-Saharan Africans. MUJAO controlled Gao during the occupation, but still maintained contact with AQIM and Ansar al-Din. In August 2013, MUJAO and its military command under the Gao Arab Ahmed Ould Amer (Ahmed al-Tilemsi, since killed by French forces) joined Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Katibat al-Mulathimeen and Katibat Mouwaqun bi dima (“those who sign in their blood”) to form al-Mourabitoun, a reference to the Almoravid empire that burst forth from the Sahara in the medieval period and eventually conquered much of north Africa and Spain.

MUJAO split in 2015, with part of the group’s fighters becoming the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara under Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, and the rest remaining with al-Mourabitoun and eventually joining JNIM. One al-Mourabitoun leader was part of JNIM’s founding group, Hassan al-Ansari, an Arab fighter from the Tilemsi valley north of Gao. He was killed near the Algerian border by French forces in February 2018, along with a few other important figures from JNIM. Al-Mourabitoun has carried out some of AQIM’s and subsequently JNIM’s larger-scale attacks. The group specialises in complex attacks on ‘soft’ targets, such as the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako in November 2015, the Cappuccino Café and HOTEL TK in Ouagadougou in January 2016, and at Grand Bassam in Côte d’Ivoire in March 2016. But it has also attacked hardened military bases such as the attack on the Mécanisme Opérationnel de Coordination (MOC) in Gao in January 2017 that killed dozens of people.

Katibat Macina

This group, led by Amadou Kouffa and a founding member of JNIM, is one of the most active jihadist armed groups in Mali today. Kouffa was an imam known in central Mali for his preaching and piety in the late 2000s, when he became more radical, possibly after having met Iyad Ag Ghali through the Da’wa movement, the local name for the Tablighi Jama’at. He joined Ansar al-Din in 2012 and began reorganising to wage a more concerted struggle in the central Mopti region. Originally referred to in press reports at the Front du Libération du Macina, Katibat Macina began operating more publicly after 2015, when it claimed an attack on the Byblos Hotel in Mopti, an attack also claimed by al-Mourabitoun. During this time, it maintained ties with Ansar al-Din, although these were not formalised until 2015 and even then not fully until the creation of JNIM.

In 2016, Katibat Macina began operating more seriously in the Niger Delta, an agriculturally rich area. It built a significant part of its outreach efforts around the discontent of local Peul populations, a lack of justice in the area, and social tensions that also helped fuel jihadist recruitment in there in 2012. It faced significant local opposition due to the harsh interpretation of the shari’a that it sought to impose and the efforts to curtail traditional celebrations linked to herders taking their animals across the river to search for pasturelands. Nonetheless, by 2017, a softened approach and growing communal conflict between Peul communities and groups of traditional hunters and local militias helped create a more conducive environment for the group. Since then, Katibat Macina has become increasingly implicated in these conflicts as well as increasing the number of attacks against United Nations forces in central Mali and Malian forces, occupying different parts of Mopti and also conducting attacks further south and west, in the regions of Segou, Koulikoro near the Mauritanian border, and also in areas around Banamba further south. It has repeatedly occupied towns in Mopti, and continues to operate widely despite Malian, UN, and increasingly French pressure. French officials claimed that a French Special Forces assault on an apparent Katibat Macina base in November 2018 killed Kouffa, only for Kouffa to appear in a video soon after, proving that he remained alive.

*****************************************************************************

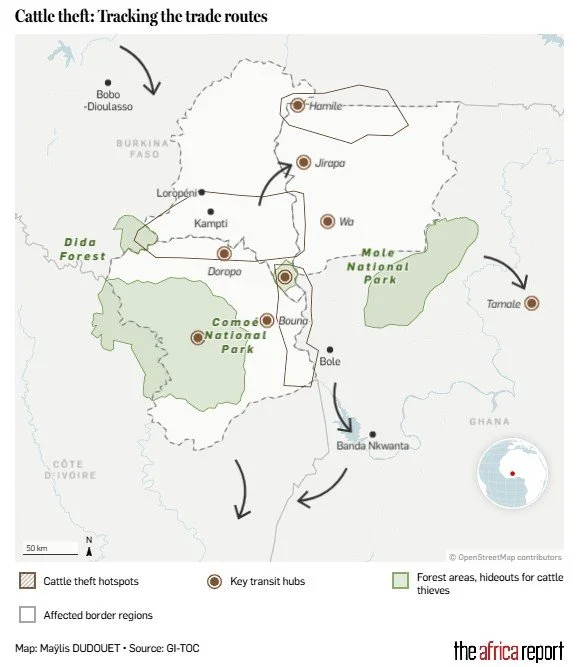

‘Bloody meat’: Burkina Faso’s livestock raids fuelling Sahel insurgency

By Pius Adeleye

Jihadists seize cattle from Fulani herders and funnel the animals into Ghana, part of a large-scale trafficking operation. Pastoralists who resist risk beatings, death or sexual violence.

On a Saturday night in April 2024, during the holy month of Ramadan, dozens of pastoralists gathered for evening prayers at a makeshift cattle camp outside Fada N’Gourma, eastern Burkina Faso’s largest town.

Ali (last name withheld), 17, had arrived late, after driving nearly a hundred cows across open grazing land some eight kilometres away. Dusty and exhausted, he performed the ablution cleansing and slipped into the prayer line.

Moments later, the devotion was broken by the grinding wheels of motorcycles. A thick cloud of dust swept over the gathering as armed men stormed the camp. They were fighters from Ansarul Islam, an Al-Qaeda-linked jihadist group under the wider Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) coalition.

Jihadists interrupting prayers to steal cattle

“They did not just come on motorcycles, they came along with two trucks,” says Ali.

For more than seven years, jihadists and bandits in Burkina Faso have raided pastoralist herds, carting cattle away by truck or on foot and selling them cheaply across borders to fund their insurgency. Those who resist risk further looting, beatings and in some cases, death or sexual violence.

“The jihadists accused my father of mixing sorcery with cattle rearing and desecrating the land,” says Ali. “They insisted on taking many of the cows to purify it.” One by one, the animals were driven onto the trucks.

“They took 167 cows and shot my older nephew in the head when he tried to resist,” he says.

For Ali, the raid left the family unsure of the future of a trade they have kept for over two centuries. The herd that once defined their livelihood has been reduced to fewer than 120 cattle.

Livestock for insurgency

For more than a decade, insurgency has spread across the Sahel, destabilising parts of West Africa. In Burkina Faso, where over 30,000 people have been killed and more than three million displaced, cross-border cattle rustling has become a vital source of financing for armed groups, fuelling the conflict.

Once home to 9.6 million cattle, 15 million goats and 10 million sheep, Burkina Faso has lost some 8 million livestock since 2017, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Most have been stolen by terror groups and militias and sold to traders across borders and in West African coastal markets to bankroll insurgencies.

For many rural Burkinabé families, livestock is a lifeline. Fulani and Tuareg pastoralists, about 10% of the population, play a key role by supplying meat, milk, hides and exports. Yet these communities remain the most exposed to raids and displacement.

In 2023, Mariam Ouedraogo, a 48-year-old widow, watched from a distance as JNIM affiliated militants slit the throat of her 54-year-old husband on their farm near Djibo, a northern town close to the Mali–Niger border. “The jihadists told us to pay taxes on the livestock by demanding about half of the 109 cows,” she says.

“When my husband refused, they killed him and took all our cows,” says Ouedraogo, who fled with her nine-month-old child.

Analysts and eight Burkinabé herders tell The Africa Report that jihadists demand livestock as taxes, or convict animal owners for ridiculous crimes. When herders are isolated with their cattle or when security is weak, raids turn into deadly looting sprees. This is a playbook of many armed groups operating on the continent.

From Mali and the Lake Chad Basin, where JNIM, Islamic State group affiliates and bandits seize herds for revenue, to Somalia and Mozambique, where Al-Shabaab plunders livestock to fund its insurgency, cattle rustling is on the rise.

A butcher speaks

Burkina Faso has sent cattle to its southern West Africa neighbours, particularly the coastal markets, since colonial times. With rising urban demand, weak local supply and long-standing trade with Ouagadougou, Ghana remained one of its biggest markets.

A World Bank data shows Burkina Faso’s 2017 livestock exports to Ghana reached nearly $1.5m, ranking ahead of Côte d’Ivoire, Benin and Togo’s similar trade with Burkina Faso.

Before JNIM’s expansion in 2017, livestock markets in Burkina Faso’s Centre-Sud and South-West bustled with cows penned in rough wooden and rustic metals, as trucks with wooden rails waited for butchers and merchants to strike deals and move the animals to mostly Ghanaian northern towns or southern cities.

But testimonies from analysts, cross-border butchers, dealers and herders in Burkina Faso and Ghana say cattle rustling by jihadists and militias in the Sahel has eclipsed the legal livestock exports to coastal neighbours, with most of the trade now controlled by armed groups and their intermediaries.

“Ivory Coast has been able to hold back the spill of terror from Burkina Faso, but Ghana and Burkina Faso still struggle along their common border,” says 62-year-old Ayamga (last name withheld), a butcher in Bolgatanga, Ghana’s Upper East Region.

For 37 years, Ayamga bought livestock from herders and slaughterhouses in southeast and south-central Burkina Faso for distribution across Ghana. However, since late 2018, he has relied mostly on intermediaries and associates of armed groups who deliver quickly from pickup trucks in border communities.

“Most meat consumed in Ghana, including those moved to the eastern coastal region, comes from bloody raids and stolen livestock,” he says. “This is bloody meat.”

Cows once sold for $650–$800 before jihadists took over the trade. Now he buys them for about $300 and resells at the old price.

Hand-in-hand

What seems like ordinary cattle rustling along the Burkina Faso–Ghana border is part of a chain that exposes deep government weakness, according to cross-border truckers, herders and butchers.

“The trafficking usually happens at night,” says Michael*, a Ghanaian truck driver who since last year has worked with middlemen moving cattle stolen by armed groups.

Before late 2022, those middlemen were mostly Fulani pastoralists aligned with JNIM in Burkina Faso.

But as violence and displacement hit Fulani communities, jihadists turned to non-Fulani butchers and cattle vendors who could slaughter and move livestock. “The armed groups seize the cattle and quickly sell them to the middlemen,” Michael says.

Some cattle are slaughtered and sold to restaurants in Burkina Faso, but many are simply loaded into trucks like his and taken to Ghana.

“Health certificates are forged, and truck drivers are assured that no law enforcement officer will stop us,” he says. “Although I have heard of a few interceptions, I have never been stopped on my route.”

In northern Burkina Faso, JNIM reportedly earned CFA25m-30m ($44,500–$53,400) per month from cattle rustling in 2021, according to a 2023 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. With the recent intensity of rustling, experts say earnings may have increased slightly.

Analysts fear daily cross-border smuggling shows the Burkinabe junta is losing ground in the insurgency and Ghana is emerging as a serious terror risk.

“There are cracks that tell us how clueless both governments are in fighting insecurity,” says a Fada N’Gourma-based security expert, asking not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

“As armed groups expand their presence in Ghana while earning money from smuggling to finance further attacks, West Africa is a ticking [time] bomb,” he says. “It is a matter of time.”

Two fronts

Ali, the teenage herder says a distant relative’s camp in Kaya, Centre-Nord region of Burkina Faso was also plundered earlier this year, not by jihadists, but by the Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie (VDP), a government-backed civilian militia set up to fight jihadist coalition.

A report from conflict monitor group ACLED notes that recruitment for the militia favours sedentary communities, leaving out Fulani and other pastoralists.

Some VDP members have been accused of stealing livestock for personal gain and targeting Fulani communities suspected of supporting jihadists, carrying out attacks and seizing their animals.

“They are stealing our lives and our animals,” says Ali, referring to both jihadists and the VDP. “That is all we have, but we cannot protect them. It is a difficult fight to defend.”

*Names have been changed to protect their identity