However, by the time of the Accra Reparations Conference in November 2023. Mr. Phillips’ position had changed and he became the major critic, leading some pushback, mostly from people within CARICOM, against the shift from the European “slave trade narrative” to the new African “Dum Diversas War” narrative. According to Dr. Phillips:

"Your view of approaching the ICJ with a "prisoner-of-war" strategy that has no historical or literature heritage (Durban, DDPA, even the PFPAD which is a derivative of Durban") is questionable from a practical point of view. "

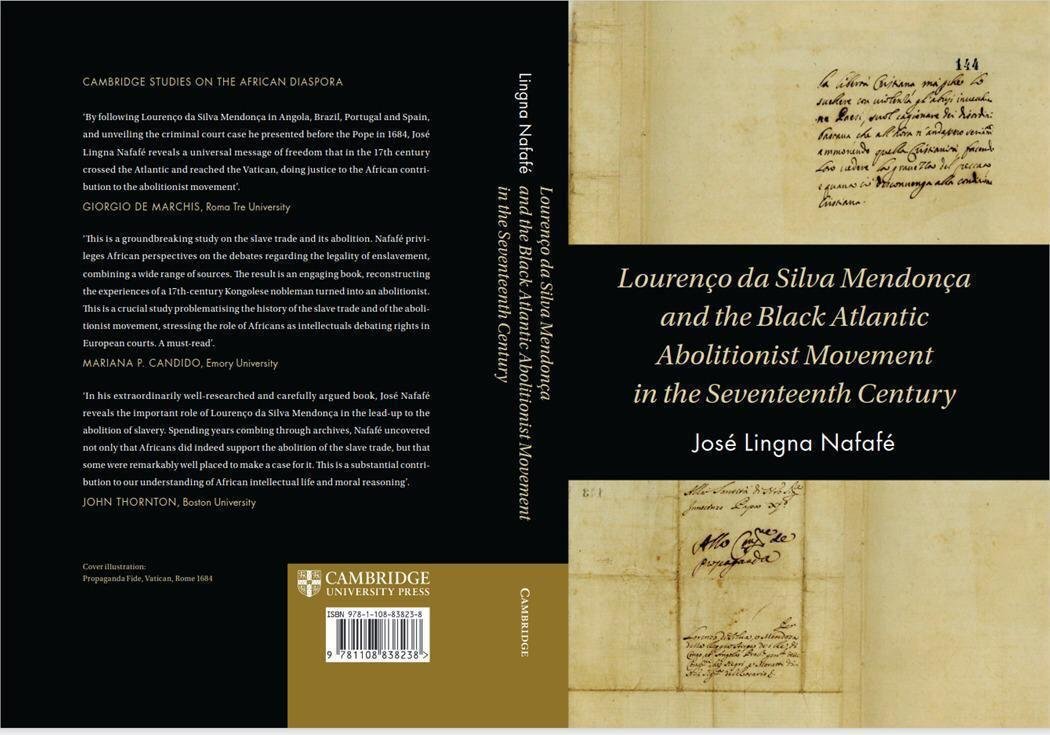

It is these two objections that I want to address with this post. José Lingna Nafafé has written a brilliant book that directly answers these erroneous ideas. Nafafé’s seminal research shows clearly that there is a “prisoner of war” strategy that has a historical, literary and LEGAL heritage but, like the historians that came before, Dr. Phillips and others are largely ignorant of. Additionally, Nafafé, usuing primary documents never before studied by the historians, effectively dismantles the argument that African tribes were complicit in slave trading and thus any reparations based on the Dum Diversas War conceptualization will provide an escape for Europeans who refuse to pay reparations. As ICJ Judge Patrick Robinson puts it, as reported by Kamm Howard,

“At a Cambridge conference I spoke at, Judge [Patrick] Robinson stated that those African ‘tribes’ that took and or forced to take direction, weapons, and reward from European nations didn't dissolve the Europeans from guilt, but enhanced European guilt.”

The excerpts below, from Nafafé’s Lourenço da Silva Mendonça and the Black Atlantic Abolitionist Movement in the Seventeenth Century will provide a concrete case study showing why the Dum Diversas War reparations claim is the African claim that has been missing from the reparations movement.

Introduction

“In 1684 Lourenço da Silva Mendonça from the kingdom of Kongo in the Indies ‘arrived in Rome to take up an important role for Black peoples.’ That role was to bring an ethical and criminal kufunda (case) before the Vatican court, which accused the nations involved in Atlantic slavery, including the Vatican, Italy, Spain and Portugal, of committing crimes against humanity. It detailed the ‘tyrannical sale of human beings . . . the diabolic abuse of this kind of slavery . . . which they committed against any Divine or Human law’. Mendonça was a member of the Ndongo royal family, rulers of Pedras (Stones) of Pungo-Andongo, situated in what is now modern Angola. He carried with him the hopes of enslaved Africans and other oppressed groups in what was a remarkable moment that, I would argue, challenges the established interpretation of the history of abolition.

Legal, moral, ethical and political debate on the abolition of slavery has traditionally been understood to have been initiated by Europeans in the eighteenth century - figures such as Thomas Buxton, Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, David Livingstone, and William Wilberforce. To the extent that Africans are recognized as having played any role in ending slavery, especially in the seventeenth century, their efforts are typically confined to sporadic and impulsive cases of resistance, involving ‘shipboard revolts’, ‘maroon communities’, ‘individual fugitive slaves’ and ‘household revolts’. Studies of these cases have never gone beyond the obvious economic disruptions caused by enslaved people resorting to poisoning, murder and attacks on plantations and their masters’ household properties. Even those former enslaved Africans who gained their freedom through sheer endeavor and subsequently argued in the strongest terms for the abolition of slavery in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano, were seen as limited in scope, without international impact and reliant on their European counterparts. Curiously, to date, no historian of slavery of West Central Africa, Africanists or Atlanticists have researched the Black Atlantic abolition movement in the seventeenth century; and those who have attempted to engage with the debate often conclude that any action driven by Africans was a localized endeavor. No historian has yet provided an in-depth study of the highly organized, international-scale, legal court case for liberation and abolition spearheaded by Lourenço da Silva Mendonça, or as Mendonça called it the ‘complaint . ..

In this book, I examine in detail how Mendonça and the historical actors with whom he was involved - such as Black Christians from confraternities in Angola, Brazil, Caribbean, Portugal and Spain - argued for the complete abolition of the Atlantic slave trade well before Wilberforce and his generation of abolitionists. . . . It reveals, for the first time, how legal debates were headed not by Europeans, but by Africans.’ . . .

To fully comprehend Mendonça’s work, it is crucial that we understand from the outset that the enslavement of Africans was part of the Portuguese conquest of West Central Africa, and the enslavement of Angolans was inseparable from Portuguese military aggression in the region. From the beginning of Portuguese settlement there in the mid-sixteenth century, war was waged against the West Central African people. This was the catalyst for the enslavement of ordinary civilians.

If we are to grasp the rationale behind the capture of enslaved people in the region and understand how they were obtained, it is crucial to recognise the role played by the Municipal City Council of Luanda, which regulated the shipment of the enslaved Angolans sent to Brazil. Indeed, it is impossible to understand the significance of Mendonça’s court case without taking account of the involvement of the Municipal City Council of Luanda in the slave trade. Central to the argument of this book, then, is the story of the destruction of Pungo-Andongo and the death of its last king, Joao (John) Hari II, who was Mendonça’s uncle. Exiled as prisoners of war, Ndongo’s royals, including Mendonça, his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins, were sent first to Salvador in Bahia, then to Rio de Janeiro and other captaincies in what is nowadays Brazil, and finally to Portugal. Crucially, to fully understand the involvement of sobas (Angolan local rulers) in the slave trade in Angola and perhaps eslewhere in Africa, I contend that it is necessary to take into account the introduction in 1626 by Fernao de Sousa, the Portuguese governor in Angola, of baculamento, a tax payment of enslaved people in place of encombros, a tax payment in produce. This is a piece of new data that has not been used by historians of West Central Africa, Africanists and Atlanticists. I argue that it had far-reaching consequences for the historiography of the region in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Unaware of this legislation, West Central African historiography on ‘taxation’, ‘wars’, ‘debt’ and ‘legal practices’ has unwittingly been prevented from truly understanding the reasons for and methods of enslavement. These historians of West Central Africa have remained ignorant of Sousa’s introduction of the baculamento. Subsequent governors and their captains in the presidio (Portuguese outpost) in Angola used the baculamento for centuries to naturalise the Atlantic slave trade. And the baculamento has remained obscure until now; most West Central African historians have taken it as accepted wisdom that slavery was an African practice, and the idea that Africans colluded in Atlantic slavery has never been challenged. Generations of scholars have studied systems of ‘taxation’, ‘wars’, ‘debt’ and ‘legal practices’ without interrogating the Portuguese institution of baculamento, which overrode local practices; instead, blame has been placed on the Angolan institutions. All Angolan soba allies of the Portuguese conquest were obliged to make a payment of 100 enslaved people annually to Portugal. This Portuguese taxation, which was named after the local baculamento practice - a tribute system- profoundly disrupted the Angolan socio-political and legal system and resulted in social upheaval. Communities and their rulers were turned against each other, a new local judicial procedure was imposed that served the interests of the Atlantic slave trade, putting judicial officers in local courts in Angola to adjudicate local cases in their own interest - what Kimbwandende K.B. Fu-Kiau called a turning point in African governance and leadership in West Central Africa. pp 1-11

Conquered, and subjected to Portuguese rule, Angolan kings and sobas loyal to the king of Portugal were made subject to annual tax payment in human beings in 1626, thus turning people into a currency. This was particularly the case for Angolan kings, because ‘native’ soldiers were recruited directly from the region where the Portuguese had established control and maintained fairs (markets). The Municipal Council of Luanda was charged with dividing land already conquered from the Angolans between the Portuguese and African war captains, so-called guerra preta. P. 12

All loyal sobas in both Angola and Kongo were conquered by the Portuguese and forced to give obedience to the Portuguese Crown in five areas: (1) pay annual tax in enslaved people to the Crown; (2) allow recruitment of soldiers for war to fight alongside the Portuguese contingent of soldiers stationed in Angola or Kongo against fellow Angolans or Kongolese; (3) open local and regional markets for the Portuguese to freely trade and impose their rule; (4) allow Portuguese priests to build churches and carry out Christian mission activities in the area; (5) allow land to be alienated for the Portuguese use. In return, sobas were granted protection from their Angolan enemies, and their children offered Portuguese education. Footnote 43, p. 12

Guerra preta was a term used to refer to Angolan soldiers who were recruited by force from the Portuguese-controlled or -conquered region of Angola Footnote 45, p. 12

On 19 November 1664, members of the Municipal Council of Luanda showed their power by lodging a complaint with the Crown that was adjudicated by the Portuguese Overseas Council, which dealth with all overseas affairs:

‘That the trade of the same Kingdom [Angola] consists only in the enslaved that is carried out in the lands of Soba’s vassals of His Majesty, that is, from presidios such as Lobolo, Dembos, Benguella, and from those that are mostly conquered by that government . . . that the most important thing that there is in that kingdom, which is in need of maintaining, is the Royal standard tax duty in slaves that they dispatch from the factory of Your Majesty. It is not that its profit is great, but also for being used for sustaining the Infantry, and to pay governors’ salaries of five presidios of hinterland, of secular priests in Kongo, and of other clergy of that kingdom, and other salaries, and budgets.’

This clearly demonstrates that the City Council’s budget depended entirely on revenues from enslavement. The slave trade in Angola was the lifeblood of the council and maintained the Portuguese project of conquest; without it, there was no Portuguese Empire. . . . P. 13

Mendonça’s family tree demonstrates that he was descended from the kings of Kongo who ruled over what is today known as West Central Africa and were the first royals to adopt Christianity in the region. Afonso I (1509-1543), the king of Kongo, is said to have been related to Mendonça’s great-grandfather, Ngola Kiluanji Kia Samba (1515-1556), king of Ndongo and Matamba. It was not a far-fetched statement, therefore, when Mendonça made the claim in the Vatican that he was descended from the ‘royal blood of the kings of Kongo and Angola’.

Given Mendonça’s origins in Kongo and Angola, Africans were demonstrably the prime campaigners for the abolition of African enslavement in the seventeenth century. In presenting his court case in the Vatican about the plight of enslaved Africans in Africa and in the Atlantic, and the oppression of Natives and New Christians in Portugal, he put forward a universal message of freedom - all these groups included people whose humanity was being denied. This challenges the accepted view that ‘the conduct of the slave trade involved the active participation of the African chiefs’. There were, indeed, many within Africa who refused to accept and actively opposed the Atlantic slave trade, and who abhorred its ideology and practice. Mendonça represented those constituencies from his own family - his grandfather, Philipe Hari I, and father, Ignacio da Silva - who were coerced into the slave trade by the Portuguese regime in Angola. P. 16

As mentioned, towards the end of 1671, after the war of Pungo-Andongo, Mendonça, his brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins were sent to Salvador, Bahia, by the governor of Luanda, Francisco de Taora “Cajanda’ (1669-1676); they lived there for eighteen months. In 1673, Mendonça was then taken to Rio de Janeiro, where he lived for, possibly, six months. After spending two years in Brazil, he was sent to Portugal in August 1673. In Portugal, he stayed at the Convent of Vilar de Frades, Braga, by order of the Portuguese Crown. His three brothers were sent to Salvador, Bahia, by the governor of Luanda, Francisco de Tavora “Cajanda” (1169-1676); they lived there for eighteen months. In 1673, Mendonça was then taken to Rio de Janeiro, where he lived for, possibly, six months. After spending two years in Brazil, he was sent to Portugal in August 1673. In Portugal, he stayed at the Convent of Vilar de Frades, Braga,too, but to different monasteries: Basto, Moreira and Selzedas. Mendonça probably studied law and theology in Braga for three or four years, from 1673 to 1676 or 1677, before returning to Lisbon, where he stayed for perhaps four years from 1677 to 1681. . . . p. 20

Gray uses the term ‘petition’ in Mendonça’s case to identify it as a request to seek a solution to alleviate the plight of the enslaved Africans; he takes no account of the legal argument embedded in the case. This is where I differ from him. According to Roman law there were different types of petition: ‘private petitions to the Roman emperor’ and ‘subscriptions of legal sources’. The first were issued to make a case for clarifying the law on behalf of private individual petitioners who had questions about it. [Siphiwe Note: much like an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ)]. Generally, the ‘petitioners had no interest in legal matters at all; they wanted honours, jobs and financial concessions’. The ‘subscriptions of legal sources’ on the other hand ‘contained formulations of principle . . . they were a response not to intellectual difficulties, but to practical ones. Petitioners went to the imperial government to get action, not advise.’ Normally they were written by legal professionals or lawyers. The presentation Mendonça delivered contained a statement of principles. For this reason, it cannot have been a petition in the first sense; it was not simply a request to end the suffering of the enslaved Africans in the Atlantic, but was a legal claim, supported by legal argument. Footnote 92 pp. 23-24

When it comes to historical sources, in 1682 the Jesuit missionaries Francisco Jose de Jaca and Epifanio de Moirans, who knew and supported Mendonça’s court case, completed their work Servi Liberi Seu Naturalis Mancipiorum Libertatis Iusta Defensio ( Freed Slaves or the Just Defence of the Natural Freedom of the Emancipated). Both also offered a critique of the capture of Africans in Africa who were then taken to the Americas as enslaved people. While renowned Spanish Jesuit Barolome De las Casas (1484-1566) defended the Indigenous Americans against slavery, the lesser-known Jaca and Moirans also spoke out against the enslavement of Africans using the legal arguments of the time. Their work, however, did not come to the fore in the debate on the Atlantic slave trade until the beginning of the 1980s, when their defence was translated from Latin to Spanish by Jose Tomas Lopez Garcia as Dos Defensores de los Esclavos Negros en el Siglo XVII (Two Defenders of the Black Slaves in the Seventeenth Century). Neither Jaca nor Moirans went to Africa as missionaries, but they both worked as Jesuit priests in Venezuela and Cuba, where they met. Their defense is a major work on the injustice of African enslavement in the Americas, and on the abolition of slavery in the Atlantic yet it is almost unknown. They analyzed in great depth the same legal terms that were used by Mendonça in the Vatican, such as ‘natural’, ‘human’, ‘divine’, ‘civil’, and ‘canon law (jus canonico)’, challenging why Atlantic slavery was being practiced against these laws. They argued that the Atlantic slave trade was illegal, stating that ‘when we begin with natural law, all men are born free’. They contended that the responsibility for those enslaved Africans in the Americas law with the pope, because ‘the lords of blind slaves with their ambition to impress the Governor (the governors in the Indies are subject to the Catholic King and the kings are subject to the Pope). This chain of responsibility made it necessary for the pope to punish the guilty parties committing such crimes, particularly the Portuguese governing authorities in Africa, Brazil and the Americas. And this obligation also implicated the pope in a crime against humanity: the Atlantic slave trade. Indeed, Jaca and Moirans stood in the witness box in the Vatican to testify on behalf of Mendonça’s court case, arguing that each ‘person is free by natural law’.

In their thesis, Jac and Moirans also asked uncomfortable questions as to why Christians bought enslaved Africans, who were captured using force, fraud, intimidation, kidnapping and theft. . . . Furthermore, they openly criticized the Atlantic slave trade and demanded that the enslaved Africans’ owners pay back what they owed the enslaved for their work and release them from bondage. For them, as for Mendonça, natural, human, divine and civil laws were universal, and had been broken by the enslavement of Africans.

Dating from the same time, the three-volume history of the Angolan wars completed by Antonio de Oliveira Cadornega in 1681 is fundamental to understanding the socio-political and cultural circumstances surrounding Mendonça’s court case, the context of the Portuguese conquest and the wars waged on the Ndongo kingdom. pp 25-27

With regard to the question of slavery in Africa, in the nineteenth century, Pedro de Carvalho, Portuguese secretary to the governor in Angola between 1862 and 1863, stated in his book, Das Origens da Escravidão Moderna em Portugal (Origins of Modern Slavery in Portugal), that ‘Africa is a land of slavery by definition. Black is a slave by birth.’ Contrary to the lone voice of Portuguese priest Father Oliveira, who in Elementos Para a História do Município de Lisboa criticized Portugal as an enslaving society by seeing it as the only country responsible for Atlantic slavery, Carvalho argued that ‘we [the Portuguese] did not invent Negroes’ slavery; we have found it there, which was the foundation of those imperfect societies.’ Other Portuguese historians have also defended Portugal’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade by echoing sentiments expressed by both Carvalho and Brasio. Among them is the nineteenth- century writer and patriarch of Lisboa, Father Francisco de S. Luis. In Nota Sobre a Origem da Escravidao e Trafico dos Negros (Reflection on the Origin of the Slavery and the Traffic of Endlaved Black Africans) - an answer to French authors Christophe de Koch and Frederic Schoell, who had accused Portugal of being responsible for the slave trade - Luis contributed to the invention of the seductive and misleading narrative that Arabs and Africans were already trading in enslaved people in Africa before Portugal became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. This has become the dominant version of the history of slavery in the region and is intended above all to shift responsibility and guilt from Europeans to Africans.

The historiography of West Central Africa initially focused on ita - ‘war’ - as an enslaved method. . . . Away from the focus on ‘war’, historians have paid particular attention to xicacos (tributes of vassalship) - or ‘taxation’. Both Beatrix Heintze and Mariana P. Candido have considered these two elements together and engaged with the significance of the fact that ‘raiding’ and ‘taxation’ were important as a source of income to cover the Portuguese administration’s expenditure in seventeenth-century Angola. Subsequently, the focus on ‘war’, ‘raiding’ and ‘taxation’ has given way to an emphasis on ‘debt’. . . . Alongside ‘debt’, historians have also examined ‘judicial proceedings’ - the tribunal de mucanos. A tribunal of mucanos means ‘legal verbal proceedings in their disputes and demands’ in the Angolan language Kimbundu. Mucanos were local courts, indigenous to West Central Africa, used to deal with legal cases. The above-mentioned historians have used these local legal structures to argue that the enslavement of Angolans was part of the West Central Africans’ culture, and that enslavement was used as a punishment for those found guilty of breaking the law. Ferreira argues that civil and criminal cases were used by sobas to enslave the guilty in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He challenges West Central African historiography that views enslaved Africans in the region as war captives and calls for its revision, deploying individual cases to reveal that enslavement was carried out through acts of kidnapping and betrayal. In a similar vein, Candido has demonstrated that in Benguela the Portuguese governing authorities were not only waging war as a method of capturing Angolans but also using debt and judicial practices to enslave them. Similarly, Joseph Calder Miller in his work Way of Death has argued that the Portuguese used the judicial system to obtain enslaved Africans in the region by enforcing debt recovery as a method in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For Miller, the enslavement of Angolans was carried out in regions far away from areas of Portuguese settlement. Alongside historiography on ita, Curto has demonstrated the problem of social conflict that was created by the slave trade in which people were ‘kidnapping’ others in revenge for enslaving their family members, particularly the slave-traders in the region. This social conflict was actually driven by the need to pay debt. pp 30-32

Mendonça began his reclamazione or court case in the Vatican not with African involvement in slavery, but rather with a bold statement of his argument and evidence about how the capture of Africans was implemented, and the methods that were deployed to enslave them. In doing so, he refuted the established thinking that Africans were willing participants in the Atlantic slave trade, and the idea that there were existing markets in Africa for enslaved Africans. Mendonça accused the Vatican, Italy, Portugal and Spain of crimes against humanity, claiming, ‘they use them [enslaved people] against human law.’ The legal concept of ‘crime against humanity’ may not have been current at the time of Mendonça’s case, although it is implicit in both natural and human laws. However, the term is frequently used in the documents Mendonça presented in the Vatican, and Roman legal jurisprudence has influenced the European legal system since that time. I believe that Mendonça’s use of the term ‘crime against humanity’ anticipated its use in modern times. Pp 43-44

The Vatican’s response was that the people involved in buying and selling enslaved Africans, particularly those found committing crimes against Christians, should be punished, and the Vatican put huge pressure on Spain and Portugal to stop such cruelty to enslaved Christians in Africa and in the Atlantic. Both Carlos II of Spain and Pedro II of Portugal, whose reigns coincided with Mendonça’s court case, wanted to abolish Atlantic slavery, but they were prevented from doing so by advisors including the Council of Indies and the Portuguese Overseas Council. The Portuguese Crown responded to the Vatican’s demand of 18 March 1684, made in response to Mendonça’s court case, by improving conditions of shipment for enslaved Africans being taken from Angola and Cape Verde to Brazil. p. 43

The Municipal Council of Luanda became the site of political intrigue, jealousy, deceit and mutiny; it was a political landscape in which the main drive was for economic gain, and the enslavement of Angolans was a key part of that package. The methods deployed to capture Angolans - through wars, pillage and treachery - formed the basis for Mendonça’s Vatican court case. . . .Mendonça’sevidence based court case challenged the established seventeenth-century assertion that Africa was a slaving society that already took part in and willingly aided the European Atlantic slave trade. His evidence demonstrated how the Atlantic slave trade operated on the ground in Africa, and how violence was used as a strategy for maintaining slavery’s existence. The accused were the Vatican, and the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish political governing authorities, and Mendonça brought together African accusers from different organizations, confraternities and interest groups including constituencies of ‘men’, ‘women’ and ‘young people’ within the confraternities themselves. pp 54-55

Joaa Hari II rebelled against the payment of tax in enslaved people and declared the independence of Pungo-Andongo from Portugal in 1671. This was a struggle that Mendonça continued to argue in the Vatican in 1684-1687. pp 55

So far, the story of slavery has been told as a narrative in which the Africans were the victims of their own crime. That crime is said to have consisted in the enslavement of their own people by their governing bodies, embedded in their socio-political, economic, religious and legal system. The abolition of Atlantic slavery, on the other hand, has mainly been told as a narrative in which the morally superior Europeans came to rescue the Africans from this very system. Both narratives made it possible for the European colonizing nations to explore Africa while exploiting African labour in a dehumanizing and violent fashion, through an intervention whose only purpose was economic gain and political power, corrupting their own Christian morality by using it to validate this domination and the turning of human beings into currency. Mendonça’s criminal court case makes it clear that these narratives are nothing more than treacherous tales aimed at justifying the unjustifiable. The case not only points up that a role in the abolition movement was taken by Africans with a sophisticated understanding of the connection between divine, natural, civil and human law but also that they showed political nous by uniting other oppressed constituencies with the Black Atlantic. Indeed, Mendonça’s universal pledge for freedom made it clear that Atlantic slavery was introduced to Africa by Europeans. It was the Vatican as a seat of Christendom with its universal ethics and the European colonizing nations that were implicated in this crime against humanity. To this day, we live with the consequences of the false criminalisation of Africans and their descendants, while the true perpetrators have not been held accountable. Mendonça’s story makes this unquestionable. pp 55-56

On 6 March 1684, when Mendonça presented his evidence-based court case in the Vatican, he began with statements on how Africans were captured. As a member of the Royal Court of Pungo-Andongo, he would have doubtless have recalled historical cases of ordinary people having been rounded up from their homes, fields and daily lives and having been enslaved in Angola; he would have experienced war; and he would have heard stories of people being seized in raids, kidnapped, and taken to the Americas as enslaved people. He would have heard from his grandfather, father, uncles, aunts and brothers - all allies of the Portuguese - about illegal wars conducted, treachery used and robbery carried out on Angolans captured, enslaved and shipped to Brazil on behalf of Portugal. His report in the Vatican confirms cases of ‘those who have been ‘abducted’, ‘kidnapped’, ‘hunted’, ‘snatched, ‘taken from the fields with fraud’ and ‘sold’ to ‘merchants’ who would in turn ‘sell them in Europe like animals’ or in the Americas for that matter.

So to begin to understand Mendonça’s criminal court case about the predicament of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic, it would be useful to start in West Central Africa, where he first experienced his people being seized and carried off into slavery in the Americas. It is essential that we locate his work in the political, legal and economic landscape of Kongo and Angola. It is also fundamental that we understand from the beginning that enslaving Africans was an integral part of the Portuguese conquest of west Central Africa. This is evident from the 1512 brief to the kings of Kongo, and later Angola, by Dom Manuel, King of Portugal. It is, therefore, impossible to draw a distinction between what we might perceive as a ‘slavery period’ in Africa at the beginning of the Portuguese encounter with West Africa or West Central Africa in general and the conquest. . . .

It was in the city councils, such as that of Luanda, that decisions were made about how Africans were to be captured and enslaved. The councils were the places in which decisions were made about conquest - the so-called ‘just war’ - and the wages of the soldiers fighting in those wars were paid. Those who disagreed with the politics of the council and its decisions were exiled to Brazil or Sao Tome. Such was the fate of the Portuguese governor of Luanda, Correia de Sousa, as well as Mendonça’s family, which was considered a threat to the ‘common good’ of the council. pp 58-59

Early historiography of West Central Africa tended to emphasize that the capture and enslavement of Angolans were a means of financing the Portuguese conquest of the region. Both Heintze and Candido have put considerable effort into demonstrating that raiding and taxation were important mechanisms of the Portuguese administration in maintaining their economic strength. Whilst Ferreira explores the idea that markets/feiras in eighteenth-century Angola were used as a means of obtaining enslaved Angolans, he indicates that their regulations were carried out by sobas. However, he concedes that the Portuguese authorities in Angola created these markets in an attempt to bridge local trading regulations. Vansina has taken this debate further and examines a different perspective on the markets, arguing that the Portuguese intervened to introduce a new ‘distance’ market in the region in enslaved Angolans, using caravans. For Vansina that market was based on the slave trade.

Thornton, Heywood and Curto have argued that the very foundation of Kongo was based on slave labour and that Afonso I (1509-1543) was complicit in the slave trade during his reign. . . . According to Thornton and Heywood, Afonso I’s cooperation with Portugal in the slave trade is attested by his letters to Manuel I, king of Portugal (1495-1521). Thornton states that the ‘warfare in this time was nevertheless important, for Nimi a Lukeni’s (1380-1420) father was said to be a raider who had sought his fortune by reducing one or another local stronghold and demanding tribute’. . . .However, Thornton appears to have been reliant on the oral sources of Father Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo (1621-1678), an Italian Jesuit priest, sent to Angola by the Vatican, in his assessment of pre-colonial Kongo . . . The difficulty with Cavazzi’s oral sources lies in the fact that they were collected in the seventeenth century and translated from Kikongo (one of the Kongo languages) into Italian, his Native language; he would have been inclined to use terms such as ‘slave’ or servus (Latin for slave) in describing situations in which conquered Africans in Europe were obliged to offer slave labour to their conquerors. . . . Missionary sources such as those collected by Cavazzi cannot be viewed as reliable, given his Christian ideology, the fact that he was ignorant of local cultural practices and the language he used in rendering terms from Kikongo in Italian. . . .

[Portuguese King] Manuel also expected Afonso I to pay back the expenses incurred for the education of his children whom he had sent to Portugal previously. He stated:

‘And I remind him [Afonso] of the great expense that we make with the sending of these ships, friars and clerics and things that we have sent him and those that have gone before you, and so the expense that is made here [in Lisbon] for the maintenance and teaching of his children, for that he must load said ships as fully as he can.’

These ‘expenses’ included personnel, Portuguese soldiers’ wages and items stated in Manuel’s 1512 Regimento that were shipped to Kongo for Afonso I, such as: armas (firearms) and escudos darmas (coats of arms), o seello das armas (cell weapons), bamdeira das armas (flags bearing coats of arms), gemtes e armadas (soldiers), oficiaes macanicos (mechanical officers or armed engineers), hu letrado (a judge) frades e clerigos (priests; friars and clerics) and other material goods. . . . These items were to help Alfonso I set up his court along the lines of those kept by Christian monarchs in Europe, ‘as from the beginning of your Christendom, we hope that in those parts there a lot will follow in the service of Our Lord and the addition to his holy Catholic Faith. . . .

What was said during the embassy of Pedro, Afonso I of Kongo’s cousin, who was sent to Portugal as an ambassador between him and Manuel, we may never know. However, what is clear from that diplomatic correspondence is that the Crown wanted enslaved people, minerals and a trade monopoly between Kongo and Portugal. From Manuel’s brief there were many issues that were not included in the Regimento. They were left for the Crown’s envoy to communicate to Afonso I directly ‘for the King, you will tell him as we spoke here with Dom Pedro his cousin’ as soon as they arrive in Kongo, such as the intention that he be given firearms and their use “for him to be well informed of the foundation [reason] we have and for giving him the firearms’. It is clear from the Regimento that he was expected to use these gifts to establish his kingdom in the likeness of Portugal: the army and arsenal were to be used in accordance with Portuguese institutions and customs, including Christianity, the Church, defense, justice and governance.

Manuel made it clear that slave-capture and metals were the main purpose of his alliance with Kongo. In other words, the goal of the Crown was to gather slaves: ‘mainly, the ships [sent to Kongo] should return full of slaves and other merchandise’. Manuel went further in his pleas to Afonso I: ‘tell him [Afonso] if slaves are traded in his country then merchandise will be taken [from Portugal] to trade them’. The Crown also promised further aid, if Afonso I cooperated; Portugal would help him when he needed it. Manuel remarked ‘with great pleasure, you will always find help and favor from us.’ The aid he received from Portugal came about because of his commitment to Christianity ‘just as we usually give and send them to the Christian Kings and Princes.’ African kings who did not profess Christianity would not meet the criteria for aid ‘as for the heathens and non-Christian kings and princes we do not send them gifts or greetings’. Afonso’s war captives from part of his own kingdom (Ndongo) were to help him fulfill his obligation to Manuel. The description makes clear that the social division he made among the inhabitants of his kingdom was an attempt to protect his people from the vicious Portuguese slave trade. Afonso did not have enslaved people in his compound. He had to go and wage war against Matamba and Ndongo to get them for the Portuguese Crown. He was armed by the Crown, which expected him to act as Christian monarchs acted. It took Afonso two years to organize the trade in enslaved people for the Portuguese Crown.

The word terreyro that Hewood interprets as a market is ambiguous. It can mean a ‘square’ but this does not necessarily imply ‘market’ as Hewood suggests. Curto argues that Afonso I opened a market in Sao Tome, when in fact it was a Portuguese market. In fact, he sent his people there to ensure that people being stolen from his kingdom were not enslaved or made into war captives. Moirans points out that a just war did not take place in Africa. . . .

In my view, the changes in taxation introduced by governor Fernao de Sousa gave birth to slave-raiding. . . . Soba allies were obliged to pay the tax in the form of human bodies - that is, enslaved people. Since this tax system was not a viable method, they resorted to raiding people to pay the tax imposed on them. . . . What is new in my interpretation is the understanding that the new tax system in enslaved people was deliberately imposed by the Portuguese and became part of the constitution of the Municipal City Council of Luanda. Based on new primary sources, I uncovered this law and realized that the taxation system based on it was designed to be permanent in West Central Africa. pp 63-68

We must also bear in mind that the acquisition of enslaved Africans was not so straightforward a transaction as we have been led to believe. There were no markets in which natural-born or captured Africans could be bought as enslaved people in Angola in the seventeenth century; such markets were only found in Portugal, Brazil and the Americas. Those who have argued for the existence of markets in Angola - such as Heintze, Miller, Ferreira and Boxer - have missed the point since they were ignorant of the 1626 changes. Documentary sources available to us do not support their speculations. From the accounts of both Antonio Bezerra Fajardo and Frei Melchior da Conceicam, there is no reason to equate kitanda (feiras or markets) with a market at which enslaved people were to be found for sale. Angolan institutions and practices cannot be held responsible for the ruthless methods (including kidnapping) used by the Portuguese to capture people in the region. Furthermore, Mendonça’s claim in the Vatican refutes this interpretation. Angolans saw kitanda as places for the exchange of goods but never as marketplaces for the sale of human beings as a business in an open space. People in Angola who had been unjustly ‘convicted’ of a crime they did not commit, ‘snatched’, ‘kidnapped’ or ‘stolen’ from their families could not be stocked and sold in a public space. The testimonies of former enslaved Africans such as Equiano, Guguano, Baquaqua and so on tell us a different story; Mendonça’s court case gives us a different, more accurate understanding of what the enslavement of Africans in the region was like. Angolan markets such as those of “S. Jose do Ecncoje, Dondo, Lembo, Lucamba and Ambaka’s presidio were created by the Portuguese’. They were attached to local presidios (Portuguese outposts) and regulated by the authority in Luanda as well as their respective captains and captains-major. Early exchange of enslaved Africans was taking place in presidios. These forced negotiations between the Portuguese and their conquered allies’ sobas were carried out in the outposts. Even the sobas did not consent to them. pp. 69-70

Since historians do not understand the underlying mechanism of enslavement in West Central Africa, the central focus of their studies is on markets as places for the enslaved or at least places in which slavery transactions took place, rather than what they were: markets for exchange of local produce. The historians created the misleading idea of a society with slave markets, believed to be governed by sobas who were seen as willing to sell human beings as goods for a transnational market in the seventeenth century and rife in the eighteenth and nineteenth century Angolan society controlled by the armed Portuguese over conquered subjects - was overlooked. footnote 83 p. 70

After the Dutch occupation of Angola (1641-1648), there was a major shift in terms of the Portuguese military organizations in Angola. From 1666, each presidio - such as Mbaka, Cambambe, Massangano or Muxima - was composed of: one captain, one captain-major and twenty-five soldiers. They were manned with pumbeiros and Quimbar (a pejorative term used to describe ‘a half-civilized Black person’ that comes back to his village after living for sometimes in towns where the Portuguese were). . . . The court’s officials employed in these outposts were charged with the task of obtaining enslaved people from local sobas under the control of Portuguese outposts by false verdicts. These controlled sobas were obliged to accept ‘forced gifts’ or ‘buttering-up gifts’ such as ocombas (okombas) and ynfucas (infucas) from the captain and captain-major of the outposts. Ocombas and ynfucas are Kimbundu words. How these terms were used in a ‘disciplinary power’ on conquered sobas in Angola are described by Sousa himself, as stated by Brasio:

‘According to Fernaou de Sousa, ocombas [okombas] consists of a pearl of wine, cloth, or another good that the captain of the presidio [Portuguese outpost] send to sobas of his district, or any other White person similarly send to the soba, with the intention that the soba pay him back. They do it with the pretense of friendship and of a good relationship. According to the same Fernao de Sousa, another gift, Ynfutas [infutas] consists of selling the ‘forced gift’ or ‘buttering up gift’ to the sobas, with kind words and ways in which it does not appear to them that they will either pay or that they will not pay it later. They give them these goods either on request or by force, and then the time passes by, they then return to demand that these gifts be paid back, under the penalty of arresting their women, children and vassals (children of Morinda) who are free, and to sell them as slaves.’

Another Kimbundu term used in the period was encombros or emcombos, meaning a muted goat. . . .Emcombos, also known as emponda or mponda, was a traditional gift given to appease a person high in the hierarchy or establish a friendship with him/her. It was a form of a contract or testament that made an agreement binding and committed both parties to peaceful interaction. To make it legal and binding required the presence of high dignitaries such as ambassadors who were witnesses of the agreement and were responsible for taking the gift with them back to the king. . . . This was not a payment in enslaved people as the Portuguese made it to be when they came to dominate politics and the economy of the time for the people they conquered in Angola.

Customary practices such as ocombas and ynfucas used for building communities in West Central Africa were used by the Portuguese for their own ends. They appropriated these terms, which sounded natural to the Mbundu people, but the way they applied them changed the Angolans’ understanding of them. To the outside world these terms would appear to be used in accordance with Mbundu practices. However, they were taken out of context and used to serve a purpose for which they were not intended - to obtain slaves. The buying and selling of enslaved people was not an established practice; the Portuguese aligned their criminal acts with the Angolans’ cultural practices. P. 71-73

In its first contact with the region of West Central Africa, Portugal sought a contractual agreement: this led to the vassalship of conquered African rulers under legal, economic, and political systems already in existence in Europe. Dom Manuel’s brief to his counterpart Afonso I stated that: ‘we will send him our judge that administer legal proceedings in his Kingdoms in accordance with our system and in the same way this applies to things relating to war that they be carrying out in our manner from here.’ The legal system in West Central Africa was thus transformed. P. 74

To maintain trade and to continue the exploration of Angola, especially with regard to the exploitation of the region’s metal deposits (with silver being of particular importance), the Portuguese Crown needed to nurture a local labour force. However, the lucrative plantations of Brazil also required African labour. Angular and Brazil both held great potential for economic gain, and the Crown sought to maintain a fine balance between the two. In both regions, however, the governor’s interests lay primarily in creating personal wealth, which was done most quickly through the Atlantic slave trade. . . . Faria, a Portuguese economist of the seventeenth century, stated that the wealth accrued from Africa made it possible for the Crown in Portugal to conquer the Far East and Brazil. He declared:

‘It is of note to those who have news of business of this Kingdom [Portugal] that the concentration and rights of the Coast of Guinea have been for many years the principal Revenue of the Crown of Portugal, and with it has become wealthy. And it gave it leverage to conquer the Orient and the New World. With it came the right of the import from Cape Verde, and Rivers of Guinea, Mina, Sao Tome and ANgola nearing 200,000 per annum.’ p. 80

The demand for African labour in Brazil’s sugar plantations and for use in general agriculture and mining increased the incentive for war in Angola to supply Angolans for the slave market. P. 81

Correia de Sousa came to the realization that he was not going to succeed in exerting his will over Angola if he continued to seek approval for all his motions from the council, which prioritized its own interests. Instead, he turned to the army to be the enabler of his political will. Soldiers wielded great power in Angola thanks to their role in the region’s conquest. Significantly, their salary had often presented a stumbling block for many governors in Angola, as they were paid from the booty that came from war, conquered lands and captured people, often in local currencies . . . . Governors had generally been extremely accommodating of army demands, recognising the need to lubricate and continue the mechanism of conquest. The City Council simply did not have the economic resources to sustain the conquest without waging illegal wars on ordinary people, including those already considered allies of Portugal. p. 85

Let us now look at how the siege of Kazanze led to treachery being employed in capturing Angolans and turning them into slaves. The attack was what Heywood and Thornton described as a ‘violent and duplicitous war against Kazanze.’ . . . Correia de Sousa knew of the problems facing the army, and knew also that to survive and fulfill his economic ambitions, he required their support. His discontented soldiers needed reimbursement in the form of land, and the territory of neighboring Kazanze presented the perfect solution. . . . Correia de Sousa’s claim to ‘give Angola to God’ translated as an ambition to loot the lands, raid, kidnap and then send the people into slavery in Brazil, Sao Tome and the Spanish West Indies.

Correia de Sousa’s war was unjust, and based on an economic rationale, and not on the Kazanze people’s rejection of Christianity, which was the main condition for waging a ‘just war’ on them. . . . The considerable value of the Kazanze’s lands, rather than the pretext he claimed - that the people of Kazanze were rebellious and a threat to Portuguese existence in the region - provided the driving motive for Correia de Sousa’s war. Soon after the war, Correia de Sousa divided Kazanze land among his Portuguese soldiers: ‘twelve leagues around Luanda were cleared and divided among veteran soldiers, so that they might till it, which will be of great benefit to the state’. The Kanzanze case, in which 1,211 people were rounded up and kidnapped, including children and women, is used here as an optic through which to comprehend the call for justice and application of law in the Atlantic, particularly with regard to the capture of enslaved people. p. 86-87

[Correia de Sousa] therefore invaded the lands of the king he was charged with serving, and hence breached the law that governed his tenure in Luanda. By declaring Kazanze a land belonging to the king of Spain, he also rendered it a Christian land, which should never have been subjected to war by the Portuguese. This makes sense of Mendonça’s claim in the Vatican that enslaved Africans in Brazil and the Americas, such as those from Kazanze, were already Christians. . . . Suffice it to say here that most of the Africans shipped to Brazil as slaves were not slaves at all, but were likewise ‘Christian’ people captured under the same circumstances as the Kazanze.

By his own account of the attack on Kazanze, Correia de Sousa appears to have used African war tactics and Angolan mercenaries to starve the enemy and force them to surrender. According to his report and as documented in a map from 1623, he encircled Kazanze with five ditches, in which he stationed five captains and sergeants. He ordered all the captains and their soldiers to cut down the trees with axes, sickles and cleavers to allow their ‘arrows to reach the enemies’. According to the battle report, the Kazanze defended themselves, wounding between twenty-five and thirty Portuguese soldiers and Angolan mercenaries. Many Kanzanze soldiers surrendered, and the Kazanze [chief] fled with five of his sobas; he was later captured and brought to Luanda. Correia de Sousa interrogated them there and, having extracted important information, ordered the beheading of the ‘Kazanze’ [chief] and two sobas for their role in ‘robbing properties in Tombo’. ‘They were brought to Luanda, where they were decapitated publicly for justice, with two other sobas allies. P. 89

Correia de Sousa’s demand for an election was in fact a deception. He called the macotas (elders or councilors) of Kazanze to Luanda to perform the ceremony there. They went in good faith, but on arrival found there was to be no election. . . . He used treachery to detain them. When they arrived, he had them rounded up and put on a ship to Brazil to become the subjects of Governor Diogo de Mendonça of Salvador, Bahia. The murinda (ordinary subjects) were then called to Luanda under the pretext of the election. All the murinda (a total of 1,211) were forced to board five ships hired by Correia de Sousa and sent to Brazil. Many of them were children and elderly men and women. Almost half of them - a total of 583 - died onboard due to the appalling and inhumane conditions. . . . Their death was beyond doubt caused by Correia de Sousa’s treachery. pp. 90-91

The case of the war in Kazane and the exile of its inhabitants to Brazil as enslaved people by Correia de Sousa in 1622 is key in enabling us to understand the socio-political environment in which Portuguese slave-trading developed in Angola, and the wider practice of slave-trading unfurled in the Atlantic. It also highlighted the raiding, kidnap and treachery used to capture ordinary people. It was in this context that Mendonça contextualized and refined his anti-slavery statement. The idea of so-called African slavery - that is, the idea that Africans were complicit in slavery - has overshadowed cases such as Kazanze’s, which is just one example among many. p. 90

Aside from Correia de Sousa’s own account, the most valuable insight into the war waged on Kazanze comes from the Catholic priests working in Angola and Kongo at the time. After the enslavement of the Kazanze, they launched an appeal at the High Court of Appeal, describing what Correia de Sousa had done. . . . All the High Court appeals argued strongly against the invasion as an unjust act and claimed that there was no justification for the exile of the Kazane people and their sobas to Salvador, Bahia. . . All the High Court Appeal writers claimed that Correia de Sousa had constructed the invasion to suit his own interests. pp. 91-92

From the evidence of [Cardoso’s report], there is a clear indication that the enslavement of the Kazane was illegal, the war against them was neither “just’ nor legal and the killing of their leaders was motivated by economic interest. . . . The individuals captured in Kazane and taken to the Americas as enslaved people were ordinary civilians, not given the protection that would have been offered to soldiers, who would come under the category of kijiko. p. 93

The Jesuit High Court of Appeal hearing states that:

‘... the vassals of Kazanze were in our allegiance, in our settlement . . . .he hired five ships and filled them with those miserable people, who came to show their allegiance; he sent them to Brazil . . . [and] left their land depopulated, without a sign of people.” pp 93-94

Crucially, the war against the Kazanze demonstrates the injustices of slavery, and how the wars used in the period to justify the enslavement of Africans were based on a fraudulent claim. . . . Moreover there is very little evidence of the already preposterous argument of a ‘just war’ being fought by Kongo and Angola, to justify the capture of people who were then enslaved. The decision to enter into war with Angolans was made unilaterally by the governor and the Municipal Council of Luanda, without consultation with the Crown in Madrid, and the grounds necessary to declare a ‘just war’, as prescribed by the Crown, were starkly absent. . . . Moreover, the substance of Madrid’s orders to the governors of Angola was that war could only be declared if Angolans were preventing the preaching of the Gospel. . . . Correia de Sousa had, in effect, violated the law set by the pope and the kings of Portugal and Spain. In Salvador, Bahia, judges were brought to give their view on the legality of the situation. Their view was clear: the exile and enslavement of the Kazanze was illegal, the captives were to be returned to Angola, and His Majesty must order Correia de Sousa to pay for their return with his own money. . . . Correia de Sousa claimed that the Kazanze were legally the spoils of war - that is to say, war captives. In other words, they were all runaway slaves: ‘for all of these persons [Kazanze], for reason of war and justice, they are slaves, if they did not come, they [soldiers] would have been obliged to enter to their forest and for not being killed, they have chosen the remedy by giving themselves up without any party’. pp 96-100