“It is only the Balantas who can be cited as lacking the institution of kingship. At any rate there seemed to have been little or no differentiation within Balanta society on the basis of who held property, authority and coercive power. . . in the case of the Balantas, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . The distribution of goods, to take a very important facet of social activity, was extremely well organized on an inter-tribal basis in the Geba-Casamance area, and one of the groups primarily concerned in this were the Balantas . . . . In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese realized that the Balantas were the chief agriculturalists and the suppliers of food to the neighboring peoples. . . .The Balantas did not allow foreigners in their midst, but they were always present in the numerous markets held in the territory of their neighbors.”

Walter Rodney, A History of The Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800

B’RASSA NCHABRA ARRIVES IN AMERICA

Sometime around 1758, B’rassa Nchabra was born in Nhacra on the Atlantic coast of modern day Guinea Bissau in West Africa. Just prior to the American Revolution, B’rassa Nchabra was captured and brought to Charleston, South Carolina as part of the illegal English slave trading in the area. According to the Negro Law of South Carolina (1740), Section I declared “all Negroes and Indians (Free Indians in amity with this Government, Negroes, mulattoes and mestizos, who are now free excepted) to be slaves.“ However, Section 4 stated that “The term Negro is confined to slave Africans (The ancient Berbers) and their descendants. It does not embrace the free inhabitants of Africa, such as the Egyptians, Moors, or the Negro Asiatics, such as Lascars.” Thus, by this statute, B’rassa Nchabra, who was a free inhabitant at the time of his capture and came from a family lineage and people that had never been enslaved and were not subjects of any political authority, was wrongfully enslaved in Charleston through illegal English maritime activity. Being so young and unable to speak English, he could not make a case in defense of his freedom.

B’rassa Nchabra was forced to accept the name “George” - named after the infamous slave owner and traitorous leader of the Sons of Liberty terrorist group, George Washington. Eventually, George and his son Jack were purchased and brought to Wake County, North Carolina by Dempsey Blake, the great, great grandson of the pirate Robert Blake. Robert Blake was himself a rebellious traitor, fighting against his King during an English civil war and defeating Royal General Prince Rupert in 1650. For this, Robert Blake was given legal sanction for his mercenary actions by being designated Commander-in-Chief of the English Fleet. He stole $14 million worth of goods from the Spanish fleet and used this money to send his sons to America and establish lucrative plantations. His descendants would become some of the largest slave owners in America.

And thus started the history of a Balanta family in America.

Shortly after B’rassa Nchabra’s arrival in America, Prince Hall and seventy three other African-American delegates presented an emigration plea to the Massachusetts Senate in January, 1773. The plea stated,

“That your Petitioners apprehend that they have, in common with all other Men, a natural & inalienable right to that freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind, & which they have never forfeited by any compact or agreement whatever—But they were unjustly dragged, by the cruel hand of Power, from their dearest friends, & some of them even torn from the Embraces of their tender Parents—From a populous, pleasant, & plentiful Country—& in Violation of the Laws of Nature & of Nations & in defiance of all the tender feelings of humanity, brought hither to be sold like Beasts of Burden, & like them condemned to slavery for Life—Among a People professing the mild religion of Jesus . . .“

Expressing the sentiment of B’rassa Nchabra and the slaves in North Carolina, a slave in Guilford County created the song “Deep River”, stating the desire to “cross over” to Africa, the home of camp meetings:

Deep River, my home is over Jordan, Deep River,

Lord, I want to cross over into camp ground;

Lord, I want to cross over into camp ground;

Lord, I want to cross over into camp ground;

Lord, I want to cross over into camp ground;

In 1787, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones formed the Free African Society (FAS) and in 1791 formed the Mother Bethel African Methodist Church. By January, 1792 1,130 slaves who sympathized with the British during the American Revolution, led by Thomas Peters and David George departed from Canada to Sierra Leone. They were followed by nearly 500 maroons from Jamaica in 1800.

From 1792 to 1861 the slaves struggle for liberation, freedom, justice and equality debated all the questions of insurrection, emigration, repatriation, integration and nationalism. None of the free people of color could agree what to do.

In 1819, Brassa Nchabra’s son Jack had a son called Yancey. That same year, Dempsey Blake willed to his son Asa Blake both Jack and Yancey. In 1850, Asa Blake willed both Jack and Yancey to his wife Siddy. Finally, in 1853, in his sixties, Jack was emancipated. However, he was still a prisoner of war in the land of his captivity. That same year, the National Convention of the Free People of Color was held in Rochester, New York. There was no delegate from North Carolina to represent Jack and Yancey Blake. However, the convention stated,

“After due thought and reflection upon the subject in which has entered profound desire to serve a common cause, we have arrived at the conclusion that the time has now fully come when the free colored people from all parts of the United States, should meet together, to confer and deliberate upon their present condition, and upon principles and measures important to their welfare, progress and general improvement.”

B’rassa Nchabra family oral history given by Eustace Blake on August 9, 1974, states

"Our forefathers were George, Jack, Yancey. Yancey Blake married Melissa Page. Yancey begat nine children by Melissa. Two boys and seven girls. Boys: Yancey Jr and John Addison. During the civil war a group of Federal Soldiers came pass the house of my grandfather (Yancey Blake), Yancey Blake Jr. joined them and was never heard from anymore.”

Indeed, Yancey Jr. was born in 1847. The U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records show him as "Henderson Blake", age 18, enlisted from 1863-1865. Yancey Jr., although free, enlisted in the army in order to fight for freedom for all slaves during the American Civil War.

In 1865, almost 150 delegates attended The Convention of the Colored People of North Carolina held at the Loyal AME Church in Raleigh, North Carolina. The President of the convention stated,

“There had never been before and there would probably never be again so important an assemblage of the colored people of North Carolina as the present in its influence upon the destinies of this people for all time to come. They had assembled from the hill-side, the mountains, and the valleys, to consult together upon the best interests of the colored people, and their watchwords, “Equal Rights before the Law.”

Writing to the Convention, William Coleman stated,

“In the first place, you should be allowed to vote as a matter of right.

There was only one State refused you this right in its organic law at the adoption of the Federal Constitution. Congress has recognized it over and over again, and many of you recollect when free persons of color voted in North Carolina . The great and good men who founded the Government felt it no degradation that the ballot-box was open to free persons of color, nor did Gen. Jackson so regard it when he called them "fellow-citizens" in his Louisiana campaign. But, further, it can easily be shown by the severest logic, that if you are not to be allowed equality before the law, then the principles laid down in the Declaration of Independence, upon which our Government is based, are words "full of sound and fury," signifying nothing."

You are four millions of people, the bone and sinew of the Southern States. If they are ever to recuperate and regain the important position they once held in the commercial world, it will be due to your energy and industry. Bat you may well ask how this is to be expected, if yea are denied the rights of freemen, if you are still to remain a proscribed and degraded race? If you are to have no other motive to incite you than a bare struggle for physical existence, if you are to feel no weight of responsibility, to be moved by no feelings of honor and patriotism, are to entertain no hopes for the elevation and advancement of your children to a higher standpoint than you now occupy, then indeed I do not see with what heart you can go to work at rebuilding the future of these shattered States.

But then, you will pay a tax to the support of the Government. Your brethren in Louisiana have been paying one for a number of years on property at the assessed value of fifteen millions of dollars. Is the colored man to have no voice in the appropriation of his money? And this, too, in a Government claiming to be Republican, and founded, after a seven years' war, upon the principle of taxation and representation!

Nothing could be more preposterous, unless it be to refuse men the right of suffrage who bare undergone all manner of hardships and dangers far rise sake of the Government; who have volunteered in the ranks of its armies, and risked their lives upon the battle-field to maintain its integrity. There is something more than a jingle of words in the copulation of "ballot and bullet."

But there is even a more terrible calamity that you may be doomed to bear than the denial of suffrage. I mean the denial of justice in our courts of law. If you are not to be admitted to the witness stand, how are you to prove your contracts? You will be at the mercy of every scoundrel who has a white skin, and is disposed to swindle you. Of course, you can have no protection for your property. How about yer persons? You may be set upon, beaten into a jelly, and outright, and although fifty respectable colored sons might have seen it, you will be without .What is to protect your wives and daughters from, the brutal last of those who would select a time when no white witnesses were present to effect their devilish designs? Formerly, your masters protected you as property; now, you must protect Yourselves as persons; and, unfortunately, the prejudice is too strong against you (I fear) to expect justice from the State. And there are other feelings, by no means so excusable as prejudice, and a policy by no means national, which will operate to keep you down. Your only hope is an appeal to Congress.”

A year later, The Freedman’s Convention was held in Raleigh, North Carolina, from October 2nd to the 5th. There were 115 delegates from sixty counties. The representatives for Wake Country were J. H. Harris, Charles Ray, Wm. Laws, S. Ellerson, H. Locket, J. R, Caswell. Moses Patterson and Wm. High, honorary members. During the Convention, although many government officials of the state of North Carolina addressed the Convention, the convention was not informed of their legal status in international law. Specifically, they were not informed that the 14th amendment was not a grant of citizenship but merely an offer of citizenship that required an acceptance of rejection. The convention was not informed of the principle of jus soli, that America had the obligation to offer citizenship to the African born on American soil but that it could not impose this citizenship. Furthermore, the the United States government, under obligation to make the offer, also had the power to create the mechanism – a plebiscite-- whereby the African could make an informed decision, an informed acceptance or rejection of the offer of American citizenship. Indeed, Section Five of the Fourteenth Amendment makes clear that Congress could pass whatever law was necessary to make real the offer of Section One. (Section Five says, 'The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.)

The first 'appropriate legislation' required at that moment -- and still required - was that which would make possible for the now free African an informed free choice, an informed acceptance or rejection of the citizenship offer.

According to to Imari Abubakari Obadele (founder of the Republic of New Africa):

“Let us recall that, following the Thirteenth Amendment, four natural options were the basic right of the African. First, he did, of course, have a right, if he wished it, to be an American citizen. Second, he had a right to return to Africa or (third) go to another country -- if he could arrange his acceptance. Finally, he had a right (based on a claim to land superior to the European's, sub- ordinate to the Indian's) to set up an independent nation of his own.

Towering above all other juridical requirements that faced the African in America and the American following the Thirteenth Amendment was the requirement to make real the opportunity for choice, for self-determination. How was such an opportunity to evolve? Obviously, the African was entitled to full and accurate information as to his status and the principles of international law appropriate to his situation. This was all the more important because the African had been victim of a long-term intense slavery policy aimed at assuring his illiteracy, dehumanizing him as a group and depersonalizing him as an individual.

The education offered him after the Thirteenth Amendment confirmed the policy of dehumanization. It was continued in American institutions . . . for 100 years, through 1965. Now, again following the Thirteenth Amendment, the education of the African in America seeks to base African self-esteem on how well the African assimilates white American folk-ways and values Worse, the advice given the African concerning his rights under international law suggested that there was no option open to him other than American citizenship. For the most part, he was co-opted into spending his political energies in organizing and participating in constitutional conventions and then voting for legislatures which subsequently approved the Fourteenth Amendment. In such circumstances, the presentation of the Fourteenth Amendment to state legislatures for whose members the African had voted, and the Amendment's subsequent approval by these legislatures, could in no sense be considered a plebiscite.

The fundamental requirements were lacking: first, adequate and accurate information for the advice given the freedman was so bad it amounted to fraud, a second stealing of our birthright; second, a chance to choose among the four options: (1) US citizenship, (2) return to Africa, (3) emigration to another country and (4) the creation of a new African nation on American soil.”

Thus, the resolutions of the Freedman’s Convention and all the similar conventions held throughout the United States were all UNIFORMED resolutions, and therefore did not meet the standard of the plebiscite for self-determination. Neither Jack or Yancey made a free and informed acceptance or rejection of the offer of citizenship and thus their legal status in the United States of America became “colonized Balanta people through forced integration.”

B’RASSA NCHABRA’S GRANDSON RETURNS TO HIS BALANTA ROOTS AS A FARMER AND BUSINESSMAN IN NORTH CAROLINA

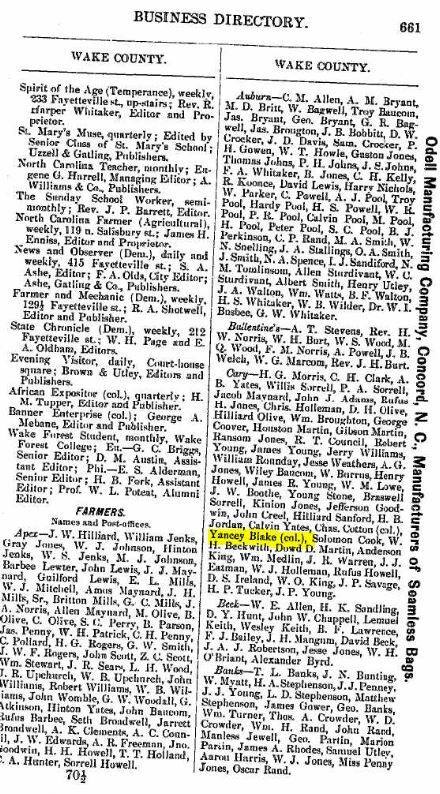

Like his ancestors in Nhacra, Yancey would return to the vocation of farming and business. By the time of the 1870 Census, Yancey Blake was listed as farmer and the city directory showed that Yancey owned 12 acres of land. He was one of only two Negroes listed in the business directory.

According to the History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church,

“Going no further back than 1815-29 . . . .We have nothing but the gentle rumbling sounds of moreal suasion against slavery. But these sounds became more and more violent from 1852 by the resolutions of the Democratic and Whig Conventions, held in the city of Baltimore, Md., when the struggles between slavery and liberty assumed a political form.”

It was during this period, in 1858, that Yancey’s son John Addison and daughter Sallie were born in House Creek, Wake County, North Carolina. Continuing with the History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church,

“On October 17, 1859, the military raid of John Brown at Harper’s Ferry was a prophetic blast of the trumpet of eternal and impartial justice, heralding the truth and the fact that just as slavery was beaten in Kansas, and driven out by ‘the sword of the Lord, and of Gideon,’ so slavery itself, enthroned on Southern soil, would be driven out of the Great Republic by the same sword of the Lord, and of Gideon. In the eye of the Christian philosopher, the former (the convention) was prophetic of the approaching civil war in favor of the perpetuity of slavery; the latter (the raid) prophetic of its complete overthrow and its utter extinction. So, then, these two events, which quickly followed each other, were the rumbling sounds of that political earthquake which shook the nation from center to circumference, and swallowed down the strongholds of the greatest despotism and absolutism that ever cursed a people and aroused the just indignation of heaven. . . .

Since the celebration of the senior centenary of the A.M.E. Church in 1866, and within the two decades found between 1863 and 1887, she has more than trebled herself. According to the official documents, the minutes of all the Annual Conventions, she then enrolled fifty thousand members. At the General Conference of 1884 she enrolled two hundred and forty-five thousand five hundred and ninety-seven. . . . Therefore it may be deemed safe to say that at the present (1887) we enrolled about three hundred thousand members, more or less. . . . It is positively affirmed by many, . . . that we now have five hundred thousand . . . .”

During the growth period, the A.M.E. Church produced the majority of the leaders of the free African people, including

Denmark Vesey (1767 - 1822) - “We are free, but the white people here won't let us be so; and the only way is to raise up and fight the whites.”

Daniel Coker (1780–1846) - “I can say, that my soul cleaves to Africa . . . I expect to give my life to bleeding, groaning, dark, benighted Africa. . . . I should rejoice to see you in this land; it is a good land; it is a rich land, and I do believe it will be a great nation, and a powerful and worthy nation. . . .If you ask my opinion as to coming, I say, let all that can, sell out and come; come, and bring ventures, to trade, etc., and you may do much better than you can possibly do in America, and not work half so hard. I wish that thousands were here. . . “

David Walker (1796 - 1830) - "If I remain in this bloody land. . . I will not live long...I cannot remain where I must hear slaves' chains continually and where I must encounter the insults of their hypocritical enslavers. . . . Fear not the number and education of our enemies, against whom we shall have to contend for our lawful right; guaranteed to us by our Maker; for why should we be afraid, when God is, and will continue, (if we continue humble) to be on our side? The man who would not fight under our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, in the glorious and heavenly cause of freedom and of God--to be delivered from the most wretched, abject and servile slavery, that ever a people was afflicted with since the foundation of the world, to the present day--ought to be kept with all of his children or family, in slavery, or in chains, to be butchered by his cruel enemies.

Martin Delany (1812 - 1885) - “Submission does not gain for us an increase of friends nor respectability, as the white race will only respect those who oppose their usurpation, and acknowledge as equals those who will not submit to their rule. . . . We must make an issue, create an event and establish for ourselves a position. This is essentially necessary for our effective elevation as a people, in shaping our national development, directing our destiny and redeeming ourselves as a race. . . .

Africa is our fatherland, we its legitimate descendants, and we will never agree or consent to see this . . . step that has been taken for her regeneration by her own descendants blasted. Our policy must be. . . Africa for the African race and black men to rule them. . . ”

Henry Highland Garnet (1815 - 1882) - “You had better all die -- die immediately, than live slaves and entail your wretchedness upon your posterity. If you would be free in this generation, here is your only hope. However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood. If you must bleed, let it all come at once rather die freemen, than live to be slaves. Let your motto be resistance! resistance! RESISTANCE! No oppressed people have ever secured their liberty without resistance. What kind of resistance you had better make, you must decide by the circumstances that surround you, and according to the suggestion of expediency.”

Henry McNeil Turner (1834 -1915) - “I used to love what I thought was the grand old flag, and sing with ecstasy about the stars and stripes, but to the negro in this country the American flag is a dirty and contemptible rag.”

During the 1890s, Turner went four times to Liberia and Sierra Leone. As bishop, he organized four annual AME conferences in Africa to introduce more American blacks to the continent and organize missions in the colonies. He also worked to establish the AME Church in South Africa, where he negotiated a merger with the Ethiopian Church. His efforts to combine missionary work with encouraging emigration to Africa were divisive in the AME Church. Nevertheless, in 1896 John Addison Blake, great grandson of B’rassa Nchabra, established the Union Bethel African Methodist Church in Cary, Wake County North Carolina. His sister, Sallie married Arch Arrington Sr., a negro and one of the largest land-owners and the first Mayor of Cary, North Carolina. Thus, by the turn of the century, B’rassa Nchabra’s great grandchildren had become one of the most prominent and powerful black families in North Carolina and in America.

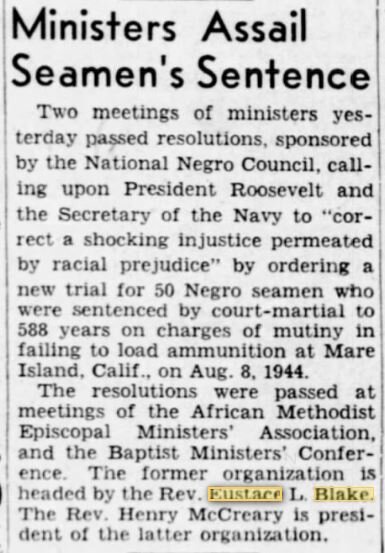

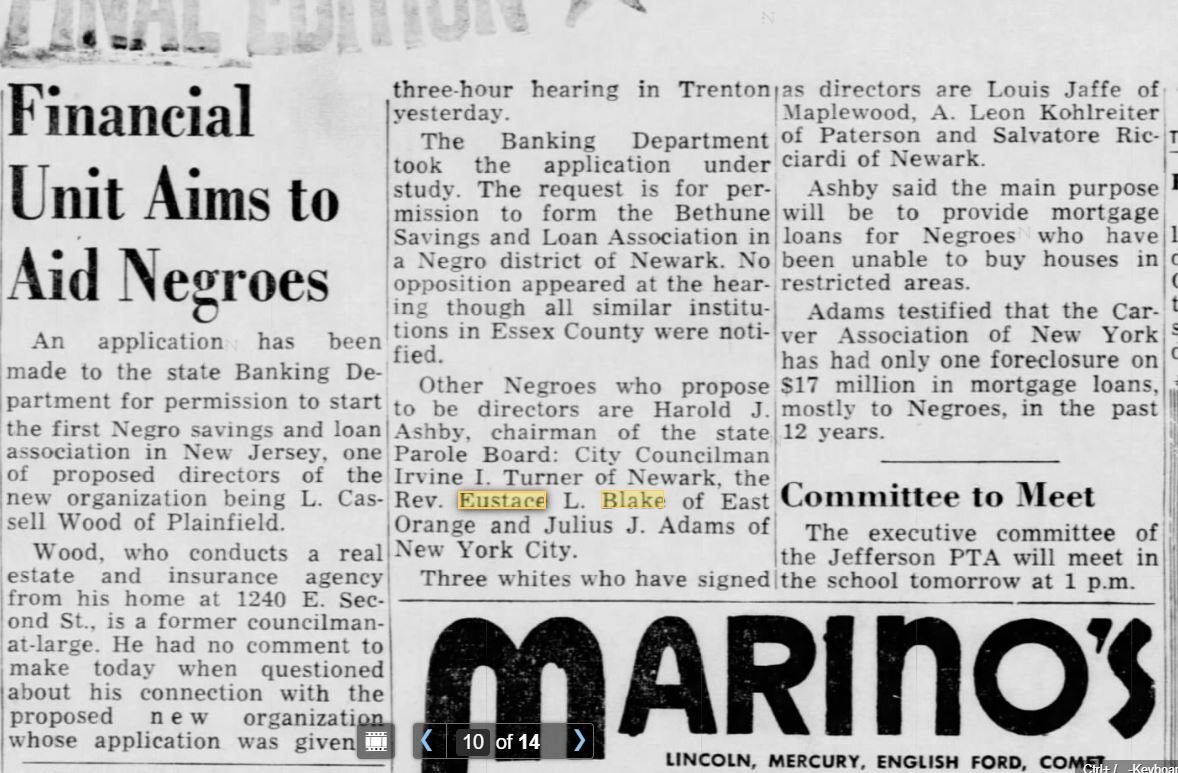

John Addison’s son Eustace Lewis Blake (B’rassa Nchabra’s great grandson) was born in 1894. In 1942, he became the 44th Pastor of Richard Allen’s historic Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia. In 1950 he went from Mother Bethel AME Church to became the pastor of the St. James AME Church in Newark, New Jersey where he served until 1966. In the book, Until Death Do Us Part, Dr. Mary White Williams recalls,

“Several years earlier, I had taken classes on ‘love, courtship, and marriage’ at St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey, and Rev. Eustace L. Blake was my instructor. He was also a fiend and a good mentor. Reverend Blake was a man of honor and integrity, and he became my ‘father in ministry.’

Reverend Eustace became a leader in both the business and spiritual community and was well-known for his principled and militant stance in defense of justice.

Philadelphia Inquirer Feb 6 1945

Courier Post Camden New Jersey November 27, 1958

The Courier News Bridgewater New Jersey January 19 1961

Reverend Eustace Blake honored for lifetime membership at NAACP 50th Anniversary in Newark.

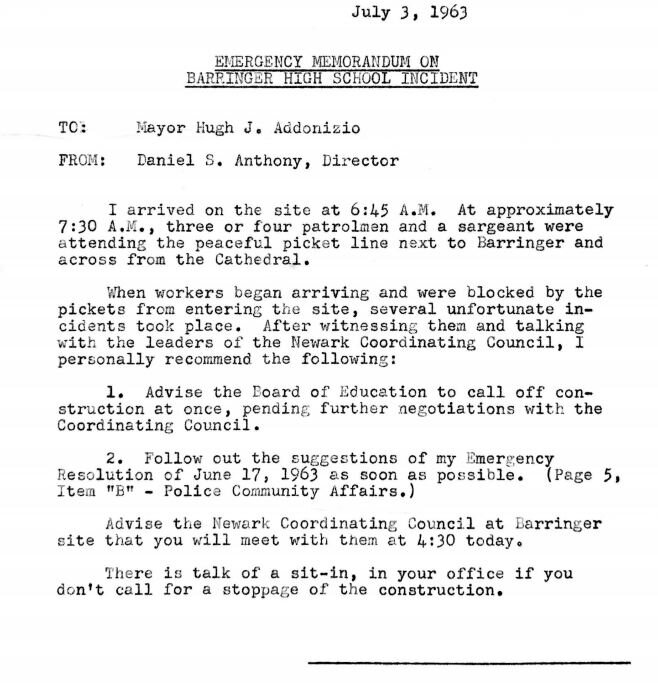

In June of 1963 , 75 protesters formed the Newark Coordinating Committee (NCC) and picketed Newark City Hall. They charged that there was discrimination in the city’s building and trade unions, apprentice programs, and job hiring. They issued an ultimatum to the Mayor: act or they will start throwing protest lines around selected construction sites.

On July 3rd, an Emergency Memorandum was sent to the Mayor and the following day, to the President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy:

The book, Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action and the Construction Industry states,

“[P]icketing and caustic negotiations . . . marked, according to the Newark Evening News, the official arrival of the civil rights movement in Newark. . . . To younger activists, the Barringer protest confirmed that liberal reform efforts not only failed to address the needs of growing Newark black communities but actively reinforced their political and economic marginalization. NCC’s tactics contrasted with the tepid emphasis on tolerance that characterized so much of the civil rights discourse and provided an alternative for activists dismayed by the essentially toothless options offered by the Mayor’s Commission. The NCC leadership of the Barringer protest marked the increasing influence of civil rights leaders who gained a foothold in the local movement by introducing mass direct action. Established black leaders, who had supported [Mayor] Addonizio and hoped to secure concessions from his administration, viewed these upstart activists with suspicion. Irvine Turner, the only African American on the Newark City Council, publicly opposed the pickets and criticized Curvin specifically. Most significantly, the Newark NAACP, averse to conflict, initially refused to join the NCC-led protest. At one ‘very tense meeting,’ Curvin was ejected at the insistence of Larrie Stalks, a prominent NAACP member and Addonizio appointee, after Curvin asked to talk about the CORE plans to bring young activists into the city for a summer organizing project.

Like the NAACP leadership, most of the Newark black clergy initially refused to support the NCC. But there were exceptions, including Reverend Dr. Eustace L Blake, who told his 2,000 congregants at St. James AME Church that

‘the price of freedom is not cheap’

and urged them to join the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC which was organized by Balanta woman Ella Baker who went on to organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee SNCC), or even CORE.”

In the aftermath of the Barringer pickets, a rally was scheduled to protest police brutality for July 29, 1964. The Association of Negro Voice, Independence and Leadership (ANVIL) was informed that the rally was an effort to incite a race riot. There was no riot at the time, but exactly three years later, the largest race riot did erupt in Newark, New Jersey.

THE NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMISSION ON CIVIL DISORDERS

The riots caused about $10 million in damages ($77 million today) and destroyed multiple plots, several of which are still covered in decay as of 2017. The riot in Newark was followed by a riot in Detroit, each of which set off a chain reaction in neighboring communities. On July 28, 1967, the President Johnson of the United States established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission) and directed it to answer three basic questions: What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again? According to the Report,

“This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white--separate and unequal. Reaction to last summer's disorders has quickened the movement and deepened the division. Discrimination and segregation have long permeated much of American life; they now threaten the future of every American. This deepening racial division is not inevitable. The movement apart can be reversed. Choice is still possible. Our principal task is to define that choice and to press for a national resolution. . . . It is time now to turn with all the purpose at our command to the major unfinished business of this nation. It is time to adopt strategies for action that will produce quick and visible progress. It is time to make good the promises of American democracy to all citizens-urban and rural, white and black, Spanish-surname, American Indian, and every minority group. Our recommendations embrace three basic principles: * To mount programs on a scale equal to the dimension of the problems: * To aim these programs for high impact in the immediate future in order to close the gap between promise and performance; * To undertake new initiatives and experiments that can change the system of failure and frustration that now dominates the ghetto and weakens our society.

In the 24 disorders in 23 cities which we surveyed:

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity: '

First Level of Intensity 1. Police practices 2. Unemployment and underemployment 3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity 4. Inadequate education 5. Poor recreation facilities and programs 6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms

Third Level of Intensity 7. Disrespectful white attitudes 8. Discriminatory administration of justice 9. Inadequacy of federal programs 10. Inadequacy of municipal services 11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices 12. Inadequate welfare programs

The results of a three-city survey of various federal programs--manpower, education, housing, welfare and community action--indicate that, despite substantial expenditures, the number of persons assisted constituted only a fraction of those in need. The background of disorder is often as complex and difficult to analyze as the disorder itself. But we find that certain general conclusions can be drawn: * Social and economic conditions in the riot cities constituted a clear pattern of severe disadvantage for Negroes compared with whites, whether the Negroes lived in the area where the riot took place or outside it. Negroes had completed fewer years of education and fewer had attended high school. Negroes were twice as likely to be unemployed and three times as likely to be in unskilled and service jobs. Negroes averaged 70 percent of the income earned by whites and were more than twice as likely to be living in poverty. Although housing cost Negroes relatively more, they had worse housing-three times as likely to be overcrowded and substandard. When compared to white suburbs, the relative disadvantage is even more pronounced. . . .

We believe that the only possible choice for America is the third-a policy which combines ghetto enrichment with programs designed to encourage integration of substantial numbers of Negroes into the society outside the ghetto. Enrichment must be an important adjunct to integration, for no matter how ambitious or energetic the program, few Negroes now living in central cities can be quickly integrated. In the meantime, large-scale improvement in the quality of ghetto life is essential. But this can be no more than an interim strategy. Programs must be developed which will permit substantial Negro movement out of the ghettos. The primary goal must be a single society, in which every citizen will be free to live and work according to his capabilities and desires, not his color.

Recommendations For National Action

We propose these aims to fulfill our pledge of equality and to meet the fundamental needs of a democratic and civilized society--domestic peace and social justice.

EMPLOYMENT

The Commission recommends that the federal government: * Undertake joint efforts with cities and states to consolidate existing manpower programs to avoid fragmentation and duplication. * Take immediate action to create 2,000,000 new jobs over the next three years--one million in the public sector and one million in the private sector-to absorb the hard-core unemployed and materially reduce the level of underemployment for all workers, black and white. We propose 250,000 public sector and 300,000 private sector jobs in the first year. * Provide on-the-job training by both public and private employers with reimbursement to private employers for the extra costs of training the hard-core unemployed, by contract or by tax credits. * Provide tax and other incentives to investment in rural as well as urban poverty areas in order to offer to the rural poor an alternative to migration to urban centers. * Take new and vigorous action to remove artificial barriers to employment and promotion, including not only racial discrimination but, in certain cases, arrest records or lack of a high school diploma. Strengthen those agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, charged with eliminating discriminatory practices, and provide full support for Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act allowing federal grant-in-aid funds to be withheld from activities which discriminate on grounds of color or race. . . . “

In 1961, the Area Redevelopment Act (ARA) was passed to aid in stimulating the economies of areas of high unemployment which had been left behind in the process of national development. The passage of the Manpower Development and Training Act in 1962 represented a greater innovation with broader provisions for institutional and on-the-job training coupled with new support of manpower research, and the requirement of an annual Manpower Report to the President. Additionally, in 1962 a task force established by US Department of Labor Secretary Willard Wirtz and reporting to his Manpower Administrator Same Merrick created the Jobs Corps. The aim of the program was to reduce unemployment. It became the central program of President Johnson’s War on Poverty agenda.

Between 1966 and 1968, Reverend Eustace Blake’s nephew, John L Blake (B’rassa Nchabra’s great, great grandson) served as the general manager for the Rochester Business Opportunity Corp (RBOC); training coordinator with the Sybron Corp, and deputy director for the Monroe Country Human Relations Commission. Referring to the RBOC, John Blake told the Times Union on March 9, 1968 that “The program will show that the Negro can succeed in his own business and industry… It will give young people a model to show that they too can be successful.”

After the Kerner Commission report, Richard Nixon made minority business enterprise a theme of his 1968 presidential campaign. After his election, President Nixon overcame meager funding of the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE) and was looking for blacks to serve in in his administration to promote minority entrepreneurship. He hired James Farmer, founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to serve as Assistant Secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. He appointed John L Blake Deputy Manpower Administrator in July, 1969.

On April 17, 1970, John Blake had dinner with President Nixon at the White House. A year and a half later, the President appointed John Blake as Director of Job Corps. In this capacity, he directed the national residential manpower training program consisting of 65 centers which aid black men and women and a $2.5 billion budget.

In an interview with About . . .Time magazine in March of 1974, John Blake said,

“When I came here, I had already said to hell with America and was on my way to Africa. I had a five-year plan; disposing of all my property, obtaining the necessary education courses for a teaching Certificate, and spending three years in the teaching field….then off to Africa.”

A year after John Blake’s dinner with President Nixon, John’s grand nephew, B’rassa Nchabra’s great, great, great, great, great grandson was born on April 14, 1971. This young man would graduate from Yale University, travel to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to work at the African Union and become the first Director of the African Union 6th Region Education Campaign. After traveling to Ghana, Togo, Benin, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, Panama and Honduras, as well as throughout the United States organizing black people to return to Africa, B’rassa Nchabra’s great, great, great, great, great grandson was given the name Siphiwe Baleka by a Council of Elders in Azania (South Africa) in 2007. In January of 2020, Siphiwe would be the first descendant of B’rassa Nchabra to return to his ancestral homeland in Nhacra, Guinea Bissau after 250 years. There he received the name,

B’rassa Mada.

Though a great effort was made to kill and erase the memory and spirit of B’rassa Nchabra’s ancestors, it managed to live and manifest itself in all the generations of B’rassa Nchabra. Through this one family, the spirit of Balanta people - great farmers, business men, and community organizers - played a significant role in American history and the struggle for justice and equality.