“Every race, nation, community on earth, no matter how high or how low it stands on the ladder of ‘civilization’, clings to a belief, a philosophy, a religion, or call it a superstition. But each clings with a tenacity that readily induces thousands and even millions of its subjects to lay down their lives in its defense. It may have been acquitted from without, or it may be the embroidery of the race’s own prophets and philosophers, and such beliefs constitute mostly those things that the particular race or nation regards as its ideals, its symbols or examples of spiritual and material perfection. In days gone by this belief nearly always took the form of reverence for a God or a number of Gods who were honored or worshiped in particular ways. . . .

The beliefs held by a particular race constitute that race’s ‘ego’. It is therefore wrong for one race to force its beliefs on another. In our witchcraft we consider it possible for one person to replace another person’s soul with his own. It amounts to the same thing. A nation’s soul is its religion.

The beliefs of any race go a long way in determining the ultimate fate of that race in the arena of human history. Many a race has been lifted to the highest heaven or cast down into the deepest pits of hell by its beliefs alone.”

- Credo Mutwa, Indaba My Children

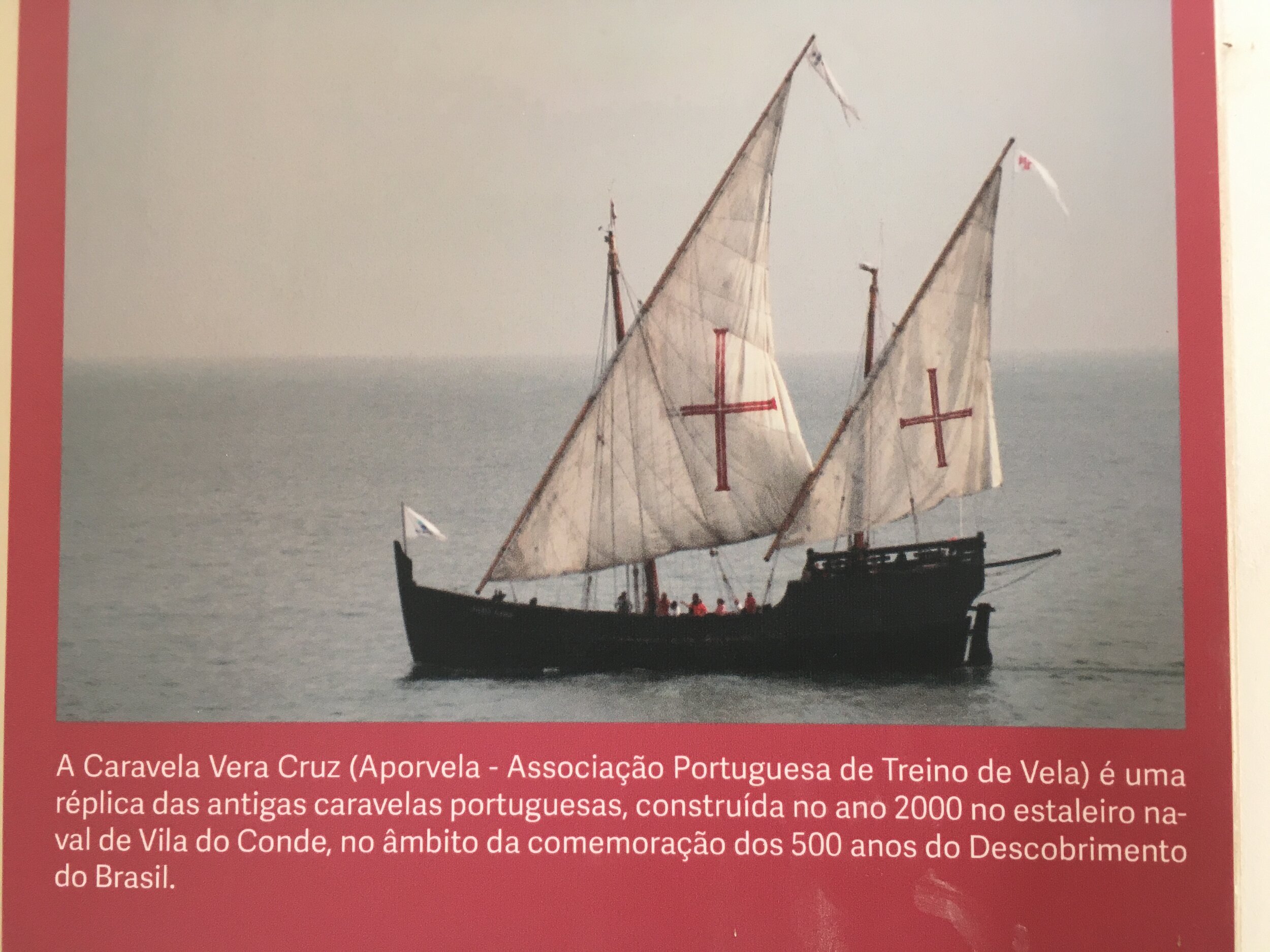

Exhibit item at the Memorial Da Escravatura E Do Trafico Negreiro de Cacheu showing a Portuguese slave ship.

Unlike Americans of European descent, most black Americans trace their ancestry to areas of Africa that, centuries ago, were not primarily part of the Christian world. Nearly eight-in-ten black Americans (79%) identify as Christian, according to Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study. This means that one of the effects of surviving the middle passage was religious conversion that persists until today.

Genetic testing through African Ancestry, however, is helping the descendants of the survivors of the middle passage to discover exactly where in Africa they came from and reclaim the heritage, culture and traditions that the white supremacist attempted to destroy and erase. Chief among them is the African spirituality that was practiced before the Christians arrived. A major challenge to the successful reparation of the spiritual and religious condition of the victims of the middle passage and subsequent slavery in the United States is the condition of Christian mental slavery. Neuroscience and behavior change theory explains why it is so difficult for black Americans, originally terrorized into becoming Christians, to release themselves from the religious indoctrination that the white supremacist used to spiritually imprison the African peoples they enslaved.

THE CHRISTIAN MISSION IN THE LAND OF GUINEA

Before we get into the neuroscience of Christian mental slavery, we need to establish the character of African spirituality before the arrival of the Christians and the original purpose and character of the first Christians who came to the land of Guinea. Before that, however, it is important to

Answer the Question: Who Created Christianity and Who Wrote the Gospels Featuring Jesus the Christ.

Kamau Makesi-Tehuti notes that,

“All of Afrika felt and feels that the Spirit reality is the primary reality and there are knowable and trainable ways to use/manipulate spirit energy for physical plane use. All of Afrika feels that members of a family who ‘die', can still be accessed and still have say so over that particular lineage. All of Afrika has an intimate relation with the Spirit world to ghe point where we can extract answers to present day concerns either through Direct interaction via rituals and/or oracular systems . . . . This defines Afrikan existence leading up to 1440 A.D. or the beginning of the modern European invasion period. We were not Christians coming to this dungeon called North America; roughly less than 1% of the total estimated Afrikans stolen, practiced a foreign religion - be that Christianity or Islam. So the other 99.8% of us were practicing, behaving and living like the above paragraph.”

The official account of the Portuguese’s first arrival in the land of Guinea in the 1440’s , according to Gomes Eannes de Azurara’s, the official royal chronicler of the King Don Affonso the Fifth of Portugal, states:

““HERE beginneth the Chronicle in which are set down all the notable deeds that were achieved in the Conquest of Guinea, written by command of the most high and revered Prince and most virtuous Lord the Infant Don Henry, Duke of Viseu and Lord of Covilham, Ruler and Governor of the Chivalry of the Order of Jesus Christ. . . . in this present chapter we should know his purpose . . . The fourth reason was because during the one and thirty years that he had warred against the Moors, he had never found a Christian king, nor a lord outside this land, who for the love of our Lord Jesus Christ would aid him in the said war. Therefore, he sought to know if there were in those parts any Christian princes, in whom the charity and the love of Christ was so ingrained that they would aid him against those enemies of the faith.

The fifth reason was his great desire to make increase in the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ and to bring to him all the souls that should be saved,—understanding that all the mystery of the Incarnation, Death, and Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ was for this sole end—namely the salvation of lost souls—whom the said Lord Infant by his travail and spending would fain bring into the true path. For he perceived that no better offering could be made unto the Lord than this; for if God promised to return one hundred goods for one, we may justly believe that for such great benefits, that is to say for so many souls as were saved by the efforts of this Lord, he will have so many hundreds of guerdons in the kingdom of God, by which his spirit may be glorified after this life in the celestial realm. . . . And if it be a fact, speaking as a Catholic, that the contrary predestinations of the wheels of heaven can be avoided by natural judgment with the aid of a certain divine grace, much more does it stand to reason that those who are predestined to good fortune, by the help of this same grace, will not only follow their course but even add a far greater increase to themselves. “

Thus, it is clear, that a chief purpose of the first Europeans to the land of Guinea was religious conversion and profiting from it. And here is the account of the first arrival in Guinea:

“And so those six caravels having set out, pursued their way along the coast, and pressed on so far that they passed the land of Sahara belonging to those Moors which are called Azanegues, the which land is very easy to distinguish from the other by reason of the extensive sands that are there, and after it by the verdue which is not to be seen in it on account of the gret dearth of water there, which causeth an exceeding dryness of the soil. . . .

Now these caravels having passed by the land of Sahara, as hath been said, came in sight of the two palm trees that Dinis Diaz had met with before, by which they understood that they were at the beginning of the land of the Negroes. . . . And at this sight they were glad indeed, and would have landed at once, but they found the sea so rough upon that coast that by no manner of means could they accomplish their purpose. And some of those who were present said afterwards that it was clear from the smell that came off the land how good must be the fruits of that country, for it was so delicious that from the point they reached, though they were on the sea, it seemed to them that they stood in some gracious fruit garden ordained for the sole end of their delight. . . . Now the people of this green land are wholly black, and hence this is called the Land of the Negroes, or Land of Guinea. Wherefore also the men and women thereof are called ‘Guineas,’ as if one were to say ‘Black Men.’ . . . And as soon as they reached the land, Stevam Affonso leapt out and five others with him, and they proceeded in the manner that the other had suggested. And while they were going thus concealed even until they neared the hut, they saw come out of it a negro boy, stark naked, with a spear in his hand. Him they seized at once, and coming up close to the hut, they lighted upon a girl, his sister, who was about eight years old. This boy the Infant afterwards caused to be taught to read and write, with all other knowledge that a Christian should have; . . . so that some said of this youth that the Infant had bidden train him for a priest with the purpose of sending him back to his native land, there to preach the faith of Jesus Christ.”

Finally, as to the character of the Christians who first came to Guinea, Gomes Azurara writes,

“But it appeareth to me, and this is my counsel, if you agree, that we attack. . . whilst they are unprepared; because they will be conquered by the disunion that will prevail amongst them through our arrival. . . . All replied that his counsel was very good, and that they would go forward at once. And when all this reasoning was done, they looked towards the settlement and saw that . . . .their women and children, were already coming as quickly as they could out of their dwellings, because they had caught sight of their enemies. But they, shouting out ‘St. James’, ‘St. George’, ‘Portugual’, at once attacked them, killing and taking all they could. Then might you see mothers foresaking their children, and husbands their wives, each striving to escape as best he could. Some drowned themselves in the water; others thought to escape by hiding under their huts; others stowed their children amont the sea-weed, where our men found them afterwards, hopint they would thus escape notice. And at last our Lord God, who giveth a reward for every good deed, willed that for the toil they had undergone in his service, they should that day obtain victory over their enemies, as well as a guerdon and a payment for all their labour and expense; for they took captive, what with men, women and children, 165 besides those that perished and were killed. And when the battle was over, all praised God for the great mercy that he had shewn them, in that he had willed to give them such a victory, and with so little damage to themselves.. . . .And when Lancarote, with those squires and brave men that were with him, had rece3ived the like news of the good success that God had granted to those few that went to the island; and saw that they had enterprised so great a deed; and that God had been pleased that they should bring it to such a pass; they were all very joyful, praising loudly the Lord God fro that he had deigned to give such help to such a handful of his Christian people. . . .And they (the people of Lisbon) seeing before their eyes what wealth those ships brought home, acquired in so short a time, and with such safety, considered, some of them, how they could get a part of that profit. . . . Then Gocalo Pacheco made captain of his caravel one Dinis Eanes de Graa, nephew of his wife in the first degree, and a squire of the Regent’s; and in the other caravels went their owners, to wit, Alvaro Gil, and Assayer of the Mint, and Mafaldo, a dweller in Setuval; and they, hoisting on their ships the banners of the Order of Christ, made their way towards Cape Branco.

It should be noted that it was much the same story when the Christians of England came to Guinea aboard the ship named Jesus of Lubeck. It was John Hawkins who first put into operation the idea of English participation in the Africo-Caribbean slave trade, when he made the celebrated voyages of 1562-3 and 1564-5. An account holds that Hawkins who claimed to be a devout Christian and missionary found the Sierra Leoneans harvesting their crops. He then proceeded to tell the natives of a god named Jesus, afterwards asking which among them sought to have Jesus as their saviour. The hundreds who raised their hands were then led to the beach and his ship “Jesus of Lubeck,” also known as “The Good Ship Jesus.” Urging the Africans to enter the ship for salvation, those who entered soon found they were barred from disembarking as the ship sailed and then got sold to Hawkins’ fellow slave merchants in the West Indies.

Jesus of Lübeck 700 tons acquired c. 1540

Herman L. Bennett, in African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern Atlantic, writes,

"At the most elemental level, natural law acknowledged native (African) sovereignty even as Christian thought, theology, and law sanctioned the enslavement of Africans. . . . Christian territorial expansion lacked a firm legal basis in canon law. In his influential commentary, Pope Innocent IV (1243) raised the question, ‘Is it licit to invade the lands that infidels possess, and if it is licit, why is it licit?’ . . . . What interested him was the problem of whether or not Christians could legitimately seize land, other than the Holy Land, that the Moslems occupied. Did . . . Christians have a general right to dispossess infidels everywhere?’ . . . In outlining his opinion, Innocent delineated a temporal domain that was simultaneously autonomous yet subordinate to the Church. Laws of nations pertained to secular matters, a domain in which a significant tendency in the Church, known as ‘dualism,’ showed increasingly less interest. But in spiritual matters, the pope’s authority prevailed, since all humans were of Christ, though not with the Church. ‘As a result,’ the medievalist James Muldoon notes, ‘the pope’s pastoral responsibilities consisted of jurisdiction over two distinct flocks, one consisting of Christians and one comprising everyone else.’ Since the pope’s jurisdiction extended de jure over infidels, he alone could call for a Christian invasion of an infidel’s domain. Even then, however, Innocent maintained that only a violation of natural law could precipitate such an attack. By adhering to the beliefs of their gods, infidels and pagans did not violate natural law. Thus, such beliefs did not provide justification for Christians to simply invade non-Christian polities, dispossess its inhabitants of their territory and freedom, or force them to convert. Innocent IV’s theological contribution resided in the fact that he accorded pagans and infidels dominium and therefore the right to live beyond the state of grace. . . .

‘by the end of the fourteenth century Innocent IV’s commentary . . . had become the communis opinion of the canonists.’

A half century later, the imperial activities of Christian rulers again raised the issue about the infidel’s dominium. . . . Despite the shifting alliance characterizing Church-state relations in the late Middle Ages, temporal authorities in Christian Europe legitimized their rule and defined their actions on scriptural grounds. Christianity represented their ontological myth, the source of their traditions, and the banner under which they marched against the infidels. Initially, the Christian princes manifested some reluctance to distance themselves from this founding ideology, since to discard Christianity would mean that their dominium merely rested on the might of one particular lineage over another. Moreover, by abandoning the pretense to just war against the infidels, Christian sovereigns risked revealing that profit motivated their desire for expansion. In the context of the late Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period, commercial considerations stood in opposition to a Christian sovereign’s purported interests in honor and justice. In the early modern period, Christianity still served multiple purposes: it legitimized the ascendancy of a particular noble house while sanctioning elite dominium over the nonelite. . . .

Since the Church defined all nonbelievers, including Saracens (a widely used term for infidels or those who willfully rejected the faith) and pagans (individuals who existed in ignorance of the faith) as the extra ecclesiam, it used the same laws and traditions in their treatment. In effect, the Church did not distinguish between the non-Christian minority in Europe and the extra ecclesiam residing beyond its de facto jurisdiction. Therefore, laws and practices shaping Church-state relations with nonbelievers in Europe set the precedent for Christian interaction with non-Christians in the wider Atlantic world. . . .

Understanding Portugal’s initial encounter with Guinea’s inhabitants requires juxtaposing the Church’s historical provenance over the extra ecclesiam against the secular state’s ascendancy. Despite the precedent established by Innocent IV’s commentary, temporal authorities drastically transformed their institutional interaction with the non-Christian minority, which carried over into their relationship with the peoples of Guinea. . . .

As the Portuguese perceived distinctions among the peoples they encountered and began acting in accordance with these perceptions, Infante Henrique sought to cultivate papal approval for his subjects’ deeds. By linking Portugal’s activities in Guinea with the conquest of Ceuta, the Infante stressed how spiritual imperatives motivated exploration along the Atlantic littoral. In his diplomatic entreaty, Infante Henrique minimized the commercial incentive and fashioned the ‘toils of that conquest’ into a ‘just war’ under the banner of a Christian Crusade. In his response a papal bull – Eugenius IV unwittingly underscored the extent of the Infante’s misrepresentation and the Church’s willingness to perpetuate this fiction. Romanus pontifex (1433), the first in a series of papal bulls issued during the fifteenth century that regulated Christian expansion, sanctioned the Infante’s request and Portugal’s alleged mission in Guinea since ‘we strive for those things that may destroy the errors and wickedness of the infidels and . . . our beloved son and noble baron Henry . . . .purposeth to go in person, with his men at arms, to those lands, that are held by them and guide his army against them.’ For Pope Eugenius, the Infante’s alleged ‘war’ constituted a Christian counteroffensive. . . . Desiring legitimacy for his commercial imperatives and wanting to prevent other princes from encroaching on Portugal’s ‘conquests,’ Infante Henrique invoked the rhetoric of a just war so as to solicit papal patronage. . . . In soliciting papal approval, Henrique manifested the ways in which the early modern prince – a temporal authority with decidedly secular interests – continued to rely on Christian legitimization. Henrique, by his actions, acknowledged the Church’s imagined jurisdiction beyond Christendom’s borders and over the extra ecclesiam. . . . Fifty years of quiet consolidation in Guinea came to an abrupt end in 1530. . . . Portuguese merchants, thus left alone, seized the opportunity to build up a profitable trade, and Portuguese missionaries undertook the evangelization of many of the negro tribes. . . . ”

Thus, we must view Christianity from its inception in West Africa - the Christian seed that was first planted in Guinea. The first visual symbol of Christianity for the people of Guinea, was the symbol of the cross that was emblazoned on the ships that approached from the west. The first action of the people whom the symbol of the cross represented was kidnapping their children while killing their parents who tried to protect them. The identified behavior of the first Christians was the continuous murderous aggression against people of Guinea. The motivation of the first Christians was to use Christianity as a justification for their greed and illegal activities. We will now discuss the neurological effects of this experience on the people of Guinea known as the Balanta.

THE BALANTA RESPONSE TO THE CHRISTIAN MISSION

Describing one of the first encounters between the Christians and the Balanta, Azurara writes,

“…When they had captured those young prisoners and articles of plunder, they took them forthwith to their boat. ‘Well were it, said Stevam Affonso to the others, ‘if we were to go through this country near here, to see if we can find the father and mother of these children, for judging by their age and disposition, it cannot be that the parents would leave them and go far off.’ . . . And then they all recognized that they were near what they sought. ‘Now,’ said he, ‘do you come behind and allow to go in front, because, if we all move forward in company, however softly we walk, we shall be discovered without fail, so that ere we come at him, whosoever he be, if alone, he must needs fly and put himself in safety; but if I go softly and crouching down, I shall be able to capture him by a sudden surprise without his perceiving me; . . . And they agreeing to this, Stevam Affonso began to move forward; and what with the careful guard that he kept in stepping quietly, and the intentness with which the Guinea labored at his work, he never perceived the approach of his enemy till the latter leapt upon him. And I say leapt, since Stevam Affonso was of small frame and slender, while the Guinea was of quite different build; and so he seized him lustily by the hair, so that when the Guinea raised himself erect, Stevam Affonso remained hanging in the air with his feet off the ground. The Guinea was a brave and powerful man, and he thought it a reproach that he should thus be subjected by so small a thing. . . . Affonso’s companions came upon them, and seized the Guinea by his arms and neck in order to bind him. And Stevam Affonso, thinking that he was now taken into custody and in the hands of the other, let go of his hair; whereupon, the Guinea, seeing that his head was free, shook off from his arms, them away on either side, and began to flee. And it was of little avail to the others to pursue him, for his agility gave him a great advantage over his pursuers in running, and in his course he took refuge in a wood full of thick undergrowth and while the others thought they had him, and sought to find him, he was already in his hut, with the intention of saving his children and taking his arms, which he had left with them. But all his former toil was nothing in comparison of the great grief which came upon him at the absence of his children whom he found gone – but as there yet remained for him a ray of hope, and he thought that perchance they were hidden somewhere, he began to look towards every side to see if he could catch any glimpse of them. . . . An although Vicente Diaz saw him coming on with such fury, and understood that for his own defense it were well he had somewhat better arms, yet thinking that flight would not profit him, but rather do him harm in many ways, he awaited his enemy without shewing him any sign of fear. And the Guinea rushing boldly upon him, gave him forthwith a wound in the face with his assegai, with the which he cut open the whole of one of his jaws; in return for this the Guinea received another wound, though not so fell a one as that which he had just bestowed. And because their weapons were not sufficient for such a struggle, they threw them aside and wrestled; and so, for a short space they were rolling one over the other, each one striving for victory. And while this was proceeding, Vicente Diaz saw another Guinea one who was passing from youth to manhood; and he came to aid his countryman; and although the first Guinea was so strenuous and brave and inclined to fight with such good will as we have described, he could not have escaped being made prisoner if the second man had not come up; and for fear of him he now had to loose his hold of the first. And at this moment came up the other Portuguese, but the Guinea, being now once again free from his enemy’s hands, began to put himself in safety with his companion, like men accustomed to running, little fearing the enemy who attempted to pursue them. And at last our men turned back to their caravels, with the small booty they had already stored in their boats. . . .

We have already told of how Rodrigueannes and Dinis Diaz sailed in company, but this is the fitting place where it behoveth us to declare certainly all that happened to them. . . . From there they began to make proof of the Guineas, in search of whom they had come there, but they found them so well prepared, that though they essayed to get on shore many a time, they always encountered such a bold defense that they dared not come to close quarters. ‘It may be,’ said Dinis Diaz, ‘that these men will not be so brave in the nighttime as by day; therefore, I wish to try what their courage is, and I can readily know it this next night.’ And this is in fact was put in practice, for as soon as the sun had quite hidden its light, he went on shore, taking with him two men, and came upon two inhabited places. . . . Then he returned to the ship and there described to Rodrigueannes and the others all that he had found. ‘We,’ said he, ‘should be acting with small judgment, were we wishful to adventure a conflict like this, for I discovered a village divided into two large parts full of habitations you know that the people of this land are not so easily captured as we desire, for they are very strong men, very wary and very well prepared in their combats. . . . ”

Thus, from the first encounter with Christians, Balantas experienced terror, trauma, brutality and grief. The survivors of this first encounter would communicate this and set the first impression of the new Christian invaders. One hundred and fifty years later, in 1594 Andre Alvares Almada is the first to mention the Balanta by name in his Trato breve dos rios de Guine, trans. P.E.H. Hair -

“The Creek of the Balantas penetrates inland at the furthest point of the land of the Buramos [Brame]. The Balantas are fairly savage blacks.”

If we remove the European Christian cultural bias, what Almada is saying is that the Balantas offered the Christians no hospitality and instead, attacked them at every opportunity. Here, the word “savage” can be meant to mean “resistant”. in 1615, Manuel Alvares commented, ‘They [Balantas] have no principle king. Whoever has more power is king, and every quarter of a league there are many of this kind.’ Twelve years later, in 1627, Alonso de Sandoval wrote that Balanta were ‘a cruel people, [a] race without a king.’

Why were the Balanta described as savage and cruel? Walter Rodney writes in A History of The Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800,

“In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese realized that the Balantas were the chief agriculturalists and the suppliers of food to the neighboring peoples. The Beafadas and Papels were heavily dependent on Balanta produce, and in return, owing to the Balanta refusal to trade with the Europeans, goods of European origin reached them via the Beafadas and the Papels. The Balantas did not allow foreigners in their midst, but they were always present in the numerous markets held in the territory of theirs neighbors.. . . The Balantas, were so hostile that the belief was widespread among the Europeans on the coast that the Balantas killed all white men that they caught. . . . The Bijago, who resided in the islands off the Cacheu and Geba estuaries, were particularly noted for their piratical activities, and steadily supplied the Portuguese with Djola, Papel, Balanta, Beafada and Nalu captives. Bijago hostilities were at their height at the turn of the seventeenth century, when the raids of their formidable war canoes forced the three Beafada rulers of Ria Grande de Buba to appeal to the king of Portugal and the Pope for protection, offering in turn to embrace Christianity. . . . Traders indicated what they felt about various groups depending upon how those groups reacted to Europeans and European trade. In Upper Guinea, the Djola and the Balanta were ‘savage cannibals’ because they did not tolerate Europeans . . . .”

According to John Horhn’s They Had No King: Ella Baker and the Politics of Decentralized Organization Among African Descended Populations,

“Furthermore, the Balanta were extremely mistrusting of outsiders not from their own lineage or tabancas. This was true even when applied to members of their own ethnic group and resulted in a culture that held loyalty to the tabancas above all else. Therefore, it was impossible for outside forces to gain influence over Balanta culture without direct conquest and the commitment of military resources. “

In Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“. . . during his journey to Guinea in the 1660s, missionary Andre de Faro intended to visit Balanta to begin to convert them to Chistianity. ’But the Balanta,’ de Faro complained, ‘are so wicked that they will not allow any whites in their lands.’ . . .

As late as 1732, European sailors were loath to venture up the Rio Geba for fear of coming in contact with Balanta age-grade warriors. . . . Spanish Capuchins specifically mentioned that Balanta ‘play a certain instrument that they call in their language bombolon’ to ‘announce the attack.’

Having assembled in what the Capuchins called ‘a great number,’ Balanta warriors struck their stranded victims quickly and with overwhelming force. ‘Upon approaching a boat,’ the Capuchins said, ‘they attack with fury, they kill, rob, capture and make off with everything.’ Such attacks happened with a great deal of regularity and struck fear in the hearts of merchants and missionaries alike. Others also commented on the frequency of Balanta raids on river vessels. On March 24, 1694, Bispo Portuense feared that he would fall victim to the Balanta when his boat, guided by grumetes, ran aground on a sandbar, probably on the Canal do Impernal, ‘very close to the territory of those barbarians.’ . . . .

Faced with an impediment to the flow of trade to their ports, the Portuguese tried to bring an end to Balanta raids. But they were outclassed militarily by skilled Balanta age-grade fighters.

Portuguese adjutant Amaro Rodrigues and his crew certainly discovered this. In 1696, he and a group of fourteen soldiers from a Portuguese post on Bissau anchored their craft somewhere near a Balanta village close to where Bissau’s Captain Jose Pinheiro had ordered the men to stage an attack. However, the Portuguese strategy was ill conceived. A sizable group of Balanta struck a blow against the crew before they had even left their boat. The Balanta killed Rodrigues and two Portuguese soldiers and took twelve people captive.

Returning to Hawthorne’s Strategies of the Decentralized,

“In 1777, Portuguese commander Ignacio Bayao reported from Bissau that he was furious that Balanta had been adversely affecting the regional flow of slaves and other goods carried by boats along Guinea-Bissau’s rivers. It was ‘not possible,’ he wrote, ‘to navigate boats for those [Balanta] parts without some fear of the continuous robbing that they have done, making captive those who navigate in the aforementioned boats.’ In response, Bayao sent infantrymen in two vessels ‘armed for war’ into Balanta territories. After these men had anchored, disembarked, and ventured some distance inland, they ‘destroyed some men, burning nine villages’ and then made a hasty retreat back to the river. Finding their vessels rendered ‘disorderly,’ the infantrymen were quickly surrounded by well-armed Balanta. Bayao lamented that ‘twenty men from two infantry companies’ were taken captive or killed. Having sent out more patrols to subdue the ‘savage Balanta’ and having attempted a ‘war’ against this decentralized people, the Portuguese found that conditions on Guinea- Bissau’s rivers did not improve.’ . . . In the early twentieth century, Portuguese administrator Alberto Gomes Pimentel explained how the Balanta utilized the natural protection of mangrove-covered areas – terrafe in Guinean creole – when they were confronted with an attack from a well-organized and well-armed enemy seeking captives or booty: ‘Armed with guns and large swords, the Balanta, who did not generally employ any resistance on these occasions. . . . pretended to flee (it was their tactic), suffering a withdrawal and going to hide in the ‘terrafe’ on the margins on the rivers and lagoons, spreading out in the flats some distance so as not to be shot by their enemies. The attackers. . . . then began to return for their lands with all of the spoils of war’.”

Continuing in Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“Occupying lands next to some of the most important interregional trade routes (the Rio Geba, Rio Cacheu, and Rio Mansoa), Balanta staged frequent attacks on merchant vessels. During such assaults, Balanta seized passengers to sell back to the communities from which they had come, ‘to black neighbors,’ who took them to Bissau or Cacheu, or to Luso Africans and their agents. Balanta also claimed all of the wares that merchants had aboard their vessels – cloth, rum, guns, powder, iron, and beads. In the late seventeenth century, Capuchins noted that ‘Balanta and the Falup’ cause notable damages and seize every day the vessels that pass by . . . and this even though the vessels are well armed.’ Further, as late as 1732, European sailors were loath to venture up the Rio Geba for fear of coming in contact with Balanta age-grade warriors. . . Staging attacks on one of the region’s principal trade corridors, Balanta greatly affected the flow of commerce. To ward off attacks, merchants had to ply coastal waters in well-armed and well-manned vessels. Further, to avoid the danger of being trapped on a sandbar or a muddy riverbank, where defense against a band of determined Balanta warriors would be very difficult, merchants had to time their voyages so as to make sure that they would clear narrow straits before tides fell. . . . Balanta conducted attacks in two ways. On some rivers, they circulated, as Bispo Vitoriano Portuense said, ‘in canoes of war’ while waiting for unsuspecting vessels to approach. Balanta canoes were dugout sections of tree trunks manned by crews of age-grade paddlers bent on capturing booty and proving their valor. However, Balanta appear to have been generally hesitant to attack the sleek, fast, and well-armed merchant vessels as they plied brackish, tidal rivers. Most often, as Barbot pointed out, Balanta preyed on the unfortunate mariners who ran their boats aground as tides fell. Tide levels vary greatly on Guinea-Bissau’s coastal rivers and can challenge even the most skilled sailors. Upon finding a stranded boat, young Balanta warriors summoned tabanca age-grade members with a bombolom. This instrument, a hollowed section of tree trunk with a horizontal slit that is struck with two sticks, is used by Balanta today to transmit detailed information over long distances. . . . If there are settlements all the way the information is passed along more easily, even if the houses are a league apart, since each tells the next.’ Similarly, Spanish Capuchins specifically mentioned that Balanta ‘play a certain instrument that they call in their language bombolon’ to ‘announce the attack.’ Having assembled in what the Capuchins called ‘a great number,’ Balanta warriors struck their stranded victims quickly and with overwhelming force.

If Balanta staged raids on villages and merchant vessels, what did they do with those they seized? Like people in other parts of Africa, Balanta exercised several options with captives. They sold, ransomed, killed, and retained them, and they did these things for reasons inexorably linked to the logic of Balanta communities.

Balanta typically divided captives into two groups: whites and Africans. Whites were often killed, dismembered, and displayed as trophies by bold young men who returned to their villages with members of their age grades to celebrate a victory. Capuchin observers noted this behavior: ‘The Balanta only hold the blacks to sell them, but as for the whites that they seize, unfailingly, they kill them. Immediately, they cut them to pieces, and they put them as trophies on the points of spears, and they go about making a display of them through the villages as a show of their valor, and he who has murdered some white is greatly esteemed.’ Barbot also left a description of Balanta killing white merchants. The inhabitants of the banks of the Rio Geba, he wrote, ‘are more wild and cruel to strangers than themselves; for they will scarce release a white man upon any conditions whatsoever, but will sooner or later murder, and perhaps devour them.’ La Courbe told a similar story. Balanta, he warned, ‘are great thieves. They pillage whites and blacks indiscriminately whenever they encounter them either on land or at sea. They have large canoes and they will strip you of everything if you do not encounter them well armed. When they capture blacks, they sell them to others, with whites they just kill them.’

Descriptions of the ferocity with which Balanta warriors staged raids, killed whites, and made trophies of white corpses or parts of them indicate that raids became a site for the display of the qualities that came to personify the ideal Balanta male. Among these qualities was bravery in the face of a powerful opponent. Balanta traditions are replete with stories of ‘men of power’ or ‘men of confidence’ – those who distinguished themselves from others in egalitarian communities by performing incredible feats. It is likely that killing whites – powerful, well-armed, and wealthy outsiders – was one way of becoming a ‘man of power.’ Whites might also have been killed as a warning to slavers to stay clear of Balanta territories. That is, brutality was a defensive mechanism, a way of protecting communities in violent times. As early as the 1560s and 1570s this brutality had earned Balanta the reputation of being ‘savages’ who ‘refuse to be slaves of ours.’”

SLAVE BREAKING AFTER THE MIDDLE PASSAGE

According to Wikipedia, Seasoning, or The Seasoning, is the term applied to the period of adjustment that was undertaken by African slaves and European immigrants following their first attack of tropical disease, during the colonization of the Americas. The term has also been applied to a period of preparation that covered adjustment to new sociocultural, labor, and geographic environments. The goal was to erase the slaves' memories prior to slavery so that their history begins and ends with their usefulness to their owners. It usually involved an older slave breaking in new ones using approaches such as less severe forms of punishment (e.g. restriction on food). Other variations involved harsher and more physically forceful procedure. This is demonstrated in the case of slave owners who believed that adaptation must begin at the earliest stage with the immediate removal of the element of subjective resistance by instilling fear and breaking the slave's spirit.

Following their sale the Africans were forced, often under torture, to accept identities suited to lifelong servitude. Having already been branded once in Africa, they would be branded a second time by their legal owners, who would also give them a Christian name. African practices and customs of all kinds were discouraged. Some captives already weakened by the horrors of the voyage committed suicide. Others died under the pressure of the 'seasoning'.

Anthony Pinn writes in Terror and Triumph: The Nature of Black Religion,

“The Middle Passage was not a consciously constructed tool by which to forge and enforce a particular existential and ontological reality. While the amenities could have been better, it was the only way of traveling to the Americas. Thus, because white sailors and indentured servants encounter, although on a much smaller scale and as persons, some conditions faced by slaves, it is worthwhile to look for other elements of the slave system that frame and reify the identity of the negro. . . . Here I turn to Michael Gomez because of his inference that the identity re-creation (and by extension the most telling enforcement of that identity) actually is incomplete with respect to the Middle Passage. Regarding slaves, he writes:

‘Whoever he was prior to boarding the slaver, something inside began to stir, giving him a glimpse of what he was to become . . . . Rites of passage were well understood in Africa, and the Middle Passage certainly qualified as one of the most challenging. As a consequence, those who bonded were taking the first faltering steps in the direction of redefinition.’

Thomas Clarkson writes in AN ESSAY ON THE SLAVERY AND COMMERCE OF THE HUMAN SPECIES, PARTICULARLY THE AFRICAN, TRANSLATED FROM A LATIN DISSERTATION, [WHICH WAS HONOURED WITH THE FIRST PRIZE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, FOR THE YEAR 1785, WITH ADDITIONS]:

“When the wretched Africans are conveyed to the plantations, they are considered as beasts of labour, and are put to their respective work. Having led, in their own country, a life of indolence and ease, where the earth brings forth spontaneously the comforts of life, and spares frequently the toil and trouble of cultivation, they can hardly be expected to endure the drudgeries of servitude. Calculations are accordingly made upon their lives. It is conjectured, that if three in four survive what is called the seasoning, the bargain is highly favourable. This seasoning is said to expire, when the two first years of their servitude are completed: It is the time which an African must take to be so accustomed to the colony, as to be able to endure the common labour of a plantation, and to be put into the gang. At the end of this period the calculations become verified, twenty thousand of those, who are annually imported, dying before the seasoning is over. This is surely an horrid and awful consideration: and thus does it appear, (and let it be remembered, that it is the lowest calculation that has been ever made upon the subject) that out of every annual supply that is shipped from the coast of Africa, forty thousand lives are regularly expended, even before it can be said, that there is really any additional stock for the colonies. When the seasoning is over, and the survivors are thus enabled to endure the usual task of slaves, they are considered as real and substantial supplies. . . .

This, situation, of a want of the common necessaries of life, added to that of hard and continual labour, must be sufficiently painful of itself. How then must the pain be sharpened, if it be accompanied with severity! if an unfortunate slave does not come into the field exactly at the appointed time, if, drooping with sickness or fatigue, he appears to work unwillingly, or if the bundle of grass that he has been collecting, appears too small in the eye of the overseer, he is equally sure of experiencing the whip. This instrument erases the skin, and cuts out small portions of the flesh at almost every stroke; and is so frequently applied, that the smack of it is all day long in the ears of those, who are in the vicinity of the plantations. This severity of masters, or managers, to their slaves, which is considered only as common discipline, is attended with bad effects. It enables them to behold instances of cruelty without commiseration, and to be guilty of them without remorse. Hence those many acts of deliberate mutilation, that have taken place on the slightest occasions: hence those many acts of inferior, though shocking, barbarity, that have taken place without any occasion at all: the very slitting of ears has been considered as an operation, so perfectly devoid of pain, as to have been performed for no other reason than that for which a brand is set upon cattle, as a mark of property. . .

This is one of the common consequences of that immoderate share of labour, which is imposed upon them; nor is that, which is the result of a scanty allowance of food, less to be lamented. The wretched African is often so deeply pierced by the excruciating fangs of hunger, as almost to be driven to despair. What is he to do in such a trying situation? Let him apply to the receivers. Alas! the majesty of receivership is too sacred for the appeal, and the intrusion would be fatal. Thus attacked on the one hand, and shut out from every possibility of relief on the other, he has only the choice of being starved, or of relieving his necessities by taking a small portion of the fruits of his own labour. Horrid crime! to be found eating the cane, which probably his own hands have planted, and to be eating it, because his necessities were pressing! This crime however is of such a magnitude, as always to be accompanied with the whip; and so unmercifully has it been applied on such an occasion, as to have been the cause, in wet weather, of the delinquent's death. But the smart of the whip has not been the only pain that the wretched Africans have experienced. Any thing that passion could seize, and convert into an instrument of punishment, has been used; and, horrid to relate! the very knife has not been overlooked in the fit of phrenzy. Ears have been slit, eyes have been beaten out, and bones have been broken; and so frequently has this been the case, that it has been a matter of constant lamentation . . .

Such then is the general situation of the unfortunate Africans. They are beaten and tortured at discretion. They are badly clothed. They are miserably fed. Their drudgery is intense and incessant and their rest short. For scarcely are their heads reclined, scarcely have their bodies a respite from the labour of the day, or the cruel hand of the overseer, but they are summoned to renew their sorrows. In this manner they go on from year to year, in a state of the lowest degradation, without a single law to protect them, without the possibility of redress, without a hope that their situation will be changed, unless death should terminate the scene.”

HOW TO MAKE A NEGRO CHRISTIAN IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In the late 1500’s, Wahunsenacawh, the mamanatowick (Paramount Chief) of the Powhatan people created a confederacy of 30 groups, each with a weroance (leader, commander) representing between 14,000 and 21,000 eastern Algonquian speaking peoples in an area of about 8,000 square miles called Tsencommacah (“Densely inhabited land”) inhabited by the Paspahegh people . Today that area is called Richmond, Virginia. In 1585, Wahunsenacawh discovered English immigrants illegally crossed the Tsencommacah border. As part of a scheme by Walter Raleigh and Richard Hakluyt to export England’s growing number of unemployed in order to create new markets and increase the riches of the British Crown while at the same time establishing a military base to attack Spanish settlements, Queen Elizabeth supported this early group of immigrants. To sell the idea, the true purpose was concealed and spreading Christianity to the Powhatan was promoted. By 1590, the settlement was found deserted. In 1607, the English immigrants set up a squatter’s camp along the north bank of the Powhatan River. Conflicts began immediately. The English immigrants fired gun shots as soon as they arrived. Within two weeks, the English immigrants had already killed Paspahegh people. By 1610, Illegal English immigration continued. Wahunsenacawh said, “Your coming is not for trade, but to invade my people and possess my country…Having seen the death of all my people thrice… I know the difference of peace and were better than any other Country.” Under the instruction of the London Company, Thomas Gates set out to “Christianize” the Powhatan Confederacy. Starting with the Kecoughtan people, Gates lured the Indians into the open by means of music-and-dance and then slaughtered them, initiating the First Anglo-Powhatan War in June. Nine years later, in 1619, THE HUMAN TRAFFICKING OF AFRICAN PEOPLE BEGAN WITH TWENTY PEOPLE BROUGHT TO TSENCOMMACAH BY SHAREHOLDERS OF THE VIRGINIA COMPANY OF LONDON. Within five years, more than 4,000 English immigrants illegally crossed into Tsencommacah. The British Government took direct control of the illegal English squatter’s camps and designated them a royal colony of England. By 1636 Colonial North America's slave trade begins when the first American slave carrier, Desire, is built and launched in Massachusetts. Massachusetts becomes the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641 and two years later, the New England Confederation of Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven adopts a fugitive slave law. Finally, in 1660, Charles II, King of England, orders the Council of Foreign Plantations to devise strategies for converting slaves and servants to Christianity.

Terry M. Turner and Paige Patterson write in God’s Amazing Grace: Reconciling Four Centuries of African American Marriages and Families,

“The salvation of slaves was an attempt by Great Britain, a Christian country, to follow the Great Commission. English laws determined their mission was to fulfill the Gospel mandate of Matt 28:20 among all people. Consequently, the afflictions suffered in slavery by early African-American marriages and families were initiated by the motivation to convert them to Christianity.

The following are instructions that were issued by King Charles to the Council of Foreign Plantations: ‘And you are to consider how much of the Natives or such as are purchased by you from other parts to be servants or slaves my be best invited to the Christian Faith, and be made capable of being baptized thereunto, it being to the honor of our Crown and of the Protestant Religion that all persons in any of our Dominions should be taught the knowledge of God, and be made acquainted with the mysteries of Salvation.’ [Siphiwe note: salvation is not a concept within traditional African spirituality since no one was born in “sin”].

However, the conventional belief among slaveholders in the Americas was that the salvation of any male or female slave granted them their freedom. This was in opposition to the King of England’s request to keep the Great Commission and evangelize Africans and Indians. This misunderstanding created a need to protect the institution of slavery.

The colonies rejected the legislation of the council and King Charles. One of the arguments offered in defense of the modern slave trade was the false idea that an African American was an infidel. This belief justified the enslavement of the African Americans. In the ancient world, all men were considered equally capable of becoming slaves, but with the conversion of the people of Northern Europe to Christianity, the custom of enslaving prisoners of war gradually ceased between Christian nations. Although between Christians and Mohammedans, the practice of enslaving war prisoners continued.

During this era, the concept of African-Americans as chattel became ingrained in the minds of European-Americans, both Christians and non-Christians. As a result, state laws legislated Black people as inferior, which promoted the idea they deserved slavery over Christianity. Additionally, it was believed that to be a Christian, one needed to complete a catechism; therefore, they must be able to read and understand the Bible. As a result, colonial states passed laws that forbade slaves from reading and writing, imposing hefty fines towards violators. South Carolina’s Act of 1740 legislated that, because chattel could not be educated, African- Americans could not be educated. This law stated that African-Americans were human, but were to be held in chattel-hood and not receive an education:

‘Whereas, the having slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great Inconveniences; Be it enacted that all and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach or cause any slave or slaves to be taught to write or shall use or employ any slave as a scribe, in any manner of writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such person or persons shall, for every such offense, forfeit the sum of one hundred pounds, current money.’

By 1667, Negro labor had become so profitable that Virginia enacted a law that declared that ‘the conferring of baptism doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom. Masters, thus freed from the risk of losing their property, could more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity. In spite of the early church requirement for reading as a method for catechism, slaves soon found they could have a relationship with Christ regardless of the traditional way of becoming a Christian. Edward Baptist discovered that slaves found Christ through spiritual emotionalism in Christianity that also served as a link to their African religious experiences:

‘Enslaved people born in Africa - still in the late 1700’s a significant percentage of Chesapeake slaves - came from a part of the world where it was common for [spirits] to throw people on the ground, to breathe in and through them, to ride worshippers’ spirits and remake their lives. These new converts demonstrated the same intensity of conversion . . . .

The real measure of salvation is a spiritually converted heart to the principles of Christianity, regardless of a person’s ability to read and write. . . . During slavery, Christian doctrines were used to justify slavery and oppression. . . . Yet, enslaved people continued to flock to churches, ‘even if ministers turned their backs on them. . . . Those who became converted Christians found mental escape from the hardships of slavery . . . .Although their inability to read and write left them with little or no theological understanding, they had an excess of spiritual songs that were sung to help them endure their suffering.”

DR. REVEREND CHARLES COLCOCK JONES AND THE RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION OF THE NEGROES

In her article, Voodoo: The Religious Practices of Southern Slaves in America, Mamaissii Vivian Dansi Hounon writes

“Contrary to popular belief, the Africans enslaved [in] America were not Christians. . . .the builders of this . . . nation were practitioners of the various African religions . . . . These spiritual practices of the Africans enslaved in America, have their ancestral origins. . . . directly from Dahomey, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, The Congo and other West African nations. . . . Though some forms of westernized Christianity made its way to many West African nations prior to the trans-Atlantic voyages, IT EFFECTED LITTLE INROADS into the lives of the millions of traditionalists Africans captured and enslaved in America.

In his book, Religion of the Slaves, Professor Terry Matthews writes,

“In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Christianity had made LITTLE OR NO IN-ROADS among Blacks for fear that they might take literally such narratives as the exodus . . . Various plantation owners expressed the concern that ‘the superstitions brought from Africa have not been wholly laid aside . . . .’[This was] often cited as evidence that the plantation slave refused to abandon African paganism for American Christianity. . . . Long before their contact with whites, Africans were a strongly religious and deeply spiritual people. . . . Indeed, the religion of modern Blacks represents a RELATIVELY MODERN DEVELOPMENT that dates back to the last several decades before slavery was brought to an end.”

Finally, Carter G. Woodson notes,

“The student of this phase of history will naturally inquire as to the actual results from all of these efforts to promote the progress of Christianity among these people. Here we are at a loss for facts as to the early period; but after 1890 when the first census of Negro churches was taken, we have some very informing statistics: and although the general census of 1900 took no account of such statistics, the United States Bureau of the Census took a special census of religious institutions in 1906, basing its report upon returns received from the local organizations themselves. . . . . Comparing these statistics of 1906 with those of 1890, one sees the rapid growth of the Negro church. Although the Negro population increased only 26.1 per cent during these sixteen years, the number of church organizations increased 56.7 per cent; the number of communicants, 37.8 per cent; the number of edifices, 47.9 per cent; the seating capacity, 54.1 per cent; and the value of the church property, 112.7 per cent.”

To the question, why? Why did we become Christians, again, Kamau Makesi-Tehuti writes in his book How To Make A Negro Christian,

“Reconnecting to our main theme, we weren’t Christians, but we became Christians. Why? Why were/are the Afrikan systems of spirituality so fearful to the caucasoids? If we all believe in a Higher Power, a Higher Force, a Supreme Deity with many different names - as we profess so profusely today - then why did/do caucasoids expend so much energy, time, manpower and resources to covert and spiritually conquer Afrikan spiritual expressions? . . . .

First and foremost - power and control. Caucasoids did not/can never fully understand our spiritual systems. . . . Back during the time of this main thesis, infiltration and co-optation was not the strategy of the day. - total banishment and destruction was, since they couldn’t understand our traditions. ALL things historically that caucasoids cannot elicit power over and cannot enact control on, must be destroyed or at best pushed into obscurity.

Secondly . . . some caucasoids knew something was up when we would bear our drums and dance in certain ways. . . . .caucasoids nonetheless feared the Afrikan language, drums and dancing, banned them and killed violators. Afrikan spiritual undercurrents were the root of most of the enslaved Afrikan rebellions.

‘. . . it was the sorcerer, the native-born Angolan, Gullah Jack at the occasion of the Denmark Vessey conspiracies in South Carolina (1822). [A] . . . .religious exercise anointed the bloody Nat Turner raids in Virginia in 1831; similarly, the conjuring ‘root man’ was blamed for fomenting mid-nineteenth century conspiracies and revolts in North Carolina, Mississippi and Louisiana (Suttles, 98-99). The connections between some kind of secretive. . . . religious exercises and violent rebellions seem fundamental to understanding the progressive history of exploited groups in the America. Slaves revived or tried to revive the old African observances under the amused or unknowing eye of plantation authority, they bound themselves in discipline to rites . . . it is only the beginning, a preface, to active, violent rebellion. For now, through the medium of his religion, the slaves ‘colonized’ self (his slave mentality) was disassociated and the slaves willfully strove to destroy the material and human trappings of the plantation authority around him.’

So we started out Afrikan traditionalists. Afrikan reality was banned and on the surface beaten out of us. Christianity then filled, however poorly, our spiritual void. After the start of the 1900’s, our Theological Misorientation: The belief in, allegiance to, or practice of a theology, religion-based ideology or an y aspects thereof that are incongruous with a) Afrocentricity (as a Black Social Theory), b) Afrikan History, and c) traditional Afrikan cosmology (e.g. harmony with nature, respect for and incorporation of the natural order inherent in the cosmos, spiritual and divine essence as the nature of the original human being, etc. . . .) increased exponentially - partly due to fear, not wanting the reprisals from caucasoid society and partly due to a lot of surface-level similarities between our innate ontology and the foreign imposed system.

Caucasoids had major debates as whether or not to ‘christianize their slaves.’

‘Stung by the effective charge of the abolitionists that the reactionary legislation of the South consigned the Negroes to heathenism, slaveholders considering themselves Christians, felt that some semblance of the religious instruction of these degraded people should be devised. It was difficult, however, to figure out exactly how the teaching of religion to slaves could be made successful and at the same time square with the prohibitory measures of the South. For this reason many masters made no effort to find a way out of the predicament. Others with a higher sense of duty brought forward a scheme of oral instruction in Christian truth or of religion without letters. The word instruction thereafter signified among the southerners a procedure quite different from what the term meant in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Negroes were taught to read and write that they might learn the truth for themselves (Woodson, 109).

Enter Dr. Reverend Charles Colcok Jones.

‘In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Christianity had made little or no in-roads among blacks for fear that they might take literally such narratives as the Exodus. But as this ‘crisis of fear’ spread across the South, suddenly rather impressive efforts were made to address the ‘needs’ of the souls of black folk. These were well organized evangelistic endeavors, particularly in those areas with large plantations. Congregations stepped up their appeals, and refined their approaches to African-Americans. Preachers and planters alike urged them to fill the gallerys, and special seating that was set aside for these honored guests. Some owners were even motivated to build ‘praise houses’ on their land, and recruited black preachers to proclaim the Lord’s name (as long -of course- as a white foreman was present to monitor things so that they did not get out of hand). Large slaveholders like the Rev Chales Colcok Jones worked to comprise a Christian primer for slaves to instill teachings that were designed as a response to the portents of revolution, and to serve as preventive measures to any insurrection.’

Lastly, here is an excerpt of what Dr. Carter G. Woodson had to say about him in his grossly under-read & under-appreciated prelude to the Miseducation of the Negro . . . :

‘Prominent among the southerners who endeavored to readjust their policy of enlightening the Black population, were Bishop William Meade, Bishop William Capers, and Rev. C.C. Jones . . . The most striking example of this class of workers was the Rev. C.C. Jones, a minister of the Presbyterian Church. Educated at Princeton . . . . and located in Georgia where he could study the situation as it was, Jones became not a theorist but a worker. . . . Meeting the argument of those who feared the insubordination of Negroes, Jones thought that the gospel would do more for the obedience of slaves and the peace of the community than weapons of war. He asserted that the very effort of the masters to instruct their slaves created a strong bond of union between them and their masters. History, he believed, showed that the direct way of exposing the slaves to acts of insubordination was to leave them in ignorance and superstition to the care of their own religion. To disprove the falsity of the charge that literary instruction given in Neau’s school in New York was the cause of a rising of slaves in 1709, he produced evidence that it was due to their opposition to becoming Christians. the rebellions in South Carolina from 1730 to 1739, he maintained, were fomented by the Spaniards in St. Augustine. The upheaval in New York in 1741 was not due to any plot resulting from the instruction of Negroes in religion, but rather to a delusion on the part of the Whites. The rebellions in Camden in 1816 and in Charleston in 1822 were not exceptions to the rule. He conceded that the Southampton Insurrection in Virginia in 1831 originated under the color of religion. It was pointed out however, that this very act itself was a proof that Negroes left to work out their own salvation, had fallen victims to ‘ignorant and misguided teachers’ like Nat Turner. Such undesirable leaders, thought he, would never have had the opportunity to do mischief, if the masters had taken it upon themselves to instruct their slaves. He asserted that no large number of slaves well instructed in the Christian religion and taken into the churches directed by White men had ever been found guilty of taking part in servile insurrections. . . .

. . . ‘his [the Negro} instruction must be an entirely different thing from the training of the Cuacasian,’ in regard to whom ‘the term education had widely different significations.’ For this reason these defenders believed that instead of giving the Negro systematic instruction he should be placed in the best position possible for the development of his imitative powers - ‘to call into action that peculiar capacity for copying the habits, mental and moral, of the superior race.’ . . .

Seeing even in the policy of religious instruction nothing but danger to the position of the slave States, certain southerners opposed it under all circumstances. Some masters feared that verbal instruction would increase the desire of slave to learn. Such teaching might develop into a progressive system of improvement, which, without any special effort in that direction, would follow in the natural order of things. Timorous persons believed that slaves thus favored would neglect their duties and embrace seasons of religious worship for originating and executing plans for insubordination and villainy. They thought, too, that missionaries from the fee States would thereby be afforded an opportunity to come South and inculcate doctrines subversive of the interests and safety of that section. It would then be only a matter of time before the movement would receive such an impetus that it would dissolve the relations of society as then constituted and revolutionize the civil institutions of the South. . . Directing their efforts thereafter toward mere verbal teaching religious workers depended upon the memory of the slave to retain sufficient of the truths and principles expounded to effect his conversion. Pamphlets, hymn books, and catechisms especially adapted to the work were written by churchmen, and placed in the hands of discreet missionaries acceptable to the slaveholders. Among other publications of this kind were Dr. Capers’s Short Catechism for the Use of Colored Members on Trial in the Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina.; A Catechism to be Used by Teachers in the Religious Instruction of Persons of Color in the Episcopal Church of South Carolina; Dr. Palmer’s Catechism; Rev John Mine’s Catechism; and C.C. Jones’s Catechism of Scripture,’ Doctrine and Practice Designed for the Original Instruction of Colored People. . . .These extracts were to ‘be read to them on proper occasions by any member of the family’.

Here should be noted the remarks of Nubia Kai from the University of Maryland discussing her book, Kuma Malinke Historiography: Sundiata Keita to Almamy Samori Toure:

“First of all, in the traditional precolonial era, griots were the principle political advisors to kings, chiefs and other high government officials. They were the mediators in international, national and local disputes. They served as ambassadors and diplomats to neighboring countries. They were the chief judicial advisors and advisors of national defense. They were also the officiators of rites of passage ceremonies, naming ceremonies, puberty rights, marriage, naming ceremonies, funerals, as well as, national inaugurations, harvest festivals, religious festivals, sporting events and other national holidays. They negotiated marriage and dowry arrangements between the families of the bride and groom. They were foremost historians, archivists, genealogists, social and cultural anthropologists, musicians and dramatic performers. Training of both male and female griots began at an early age in a peripatetic fashion through close association with their parents and of other family members who were also griots. By the time a griot child reaches adulthood, they have already learned and absorbed a good deal of Mandinka cultural history. Then they may travel widely to learn the local histories of specific regions of the empire and become apprentices of master griots where they may study anywhere from 10 to 20 years. By the time a griot reaches the last stage of initiation achieving the title of [foreign words spoken] "master of the word" they have a mass a phenomenal amount of very detailed knowledge of every aspect of the Mandinka culture, society, history, politics, art, genealogy, and in most cases have mastered a musical instrument or instruments, elocution, singing, dancing and dramatic performance. They have the repositories of history with a repertoire that can fill a library. The astonishing amount of information that the griot's stores in his or her brain corroborates the disarming fact that human beings use only 10% of their brain capacity. For the griots seem use a much larger percent and confirm the singly infinite capacity of the human brain to a mass knowledge. The griots then are far more than storytellers. The use storytelling techniques and devices in their explication of history, yet that skill is a drop in the bucket of a multifaceted range of skills at expertise and numerous professions. The musician, performer, genealogist, historian are in inseparable in Mandinka historiography. The intellectual and esthetic are inseparable. In a culture where there is no separation between the sacred and the profane, the individual and the collective community, the corporal and spiritual worlds, the historical artistic paradigm is only a reflection of the way art is integrated into the daily life of the people. History to the Mandinka griot is a form of divine revelation; a sacred text that provides human beings with a spiritual ethical map on how to arrive by degrees to their initial state of perfection. Since life in this cosmological scheme is sacred, the recording of social and cultural life is also sacred, thus, the histories in traditional cultures are denoted as sacred histories. The most important event in history, in Mali's history, in any history, according to the griot [foreign name spoken] who the picture you have there and who I dedicated the book to, is the birth of a child for when a child is born a miniature universe is born, hence ego that is the ego that we see in the genealogical charts, the individual is the center of the world and the center of history. How does a Mandinka griot accomplish the task of infusing history into the souls of every Malian citizen? The answer lies in a historiography rooted in a correspondent cosmogony and a deployment of esthetic devices designed to engage the body simultaneously at an intellectual, emotional and spiritual level. Drama, ritual and art play a prominent role in the daily life of traditional African society and a special role in enlivening, interpreting and transmitting history so that histories powers of transformation are actualized. . . .

Mythic symbolism attempts to explain the spiritual nature of men and women and their inextricable connection to universal order. In traditional cultures, myths, legends, epics are regarded as real history while fairytales, animal [inaudible] tales are generally categorized as fictional. In the modern world, the extreme methodology of Aristotelian logic combined with social Darwinism relegated myth to the fantastic fictions of the infantile primitive mind. Nevertheless, and despite the intellectual hubris that generated the disfigurement of myth, there was an undeniable consensus regarding its transformational power and peculiar ability to shape and transmute consciousness among some of the most influential religious scholars and psychologists, Mircea Eliade, Bachofen, Carl Jung,[inaudible], Sigmund Freud, W.T. Stevenson and Joseph Campbell turned a psychoanalytical eye on mid and formulated at least a precise explanation of this functionality. The idea that myths are invented in order to rationalize and explain human existence was radically challenged once scholars isolated and carefully observed the cause effect relationship of myth and consciousness. Joseph Campbell, one of the foremost scholars of mythology defines for functions of living myths and their ritual enactments. "The first is what I have called the mystical function to awaken and maintain in the individual a sense of all and gratitude in relation to the mystery dimension of the universe not so that he lives in fear of it but so that he recognizes that he participates in it since the mystery of its being is the mystery of his own deep being as well. The second function of mythology is to offer an image of the universe that will be in accord with the knowledge of the time, the sciences and fields of action, of the folk to whom the mythology is addressed. The third function of the living mythology is to validate, support and imprint the norms of a given specific moral order that namely of the society in which the individual is to live. And the fourth is to guide him, stage by stage in health, strength and harmony of spirit through the whole foreseeable course of a useful life." And that is from Joseph Campbell. . . .

Historical myths record history as it actually occurs though they may be embellished with extended metaphors, hyperboles, parables, proverbs, imagery, symbolism and philosophical analysis. In the epic, the narrative is usually built around the life and deeds of the hero. The circumstances of his or her birth, childhood, trials, obstacles, triumphs and their impact on the course of history. Epics even more than creation myths, are constructed to personalize experience through the vicarious revelation of the hero who's acts epitomize the most cherished human principles; faith, courage, integrity, generosity, compassion, loyalty, intelligence. Through these virtues the hero is able to [inaudible] all opposition and obstacles and achieve a personal and public victory. Often the monomythic journey is a national parable explaining the philosophical and ethical ideas of the society through the life and character of the culture hero. . . . The finite and the infinite, man's mortality and immortality are brought into conflict with each other through the hero's action but the two worlds, the material and spiritual also overlap and the conflicts are resolved through him. . . . In Mandinka society, every social ceremonial whether secular or religious gave rise to colorful, flamboyant and elaborate theatrical performances that involved the entire community and lasted for days or weeks. As [foreign name spoken] noted, everything in them is displayed and performed. Social practices are in a state of permanent dramatization. Ritual drama permeates the society on a daily basis and infuses its members with an experiential sense of history, culture, morality and spirituality. History, culture, politics, and social practice are consistently explicated through multiple forms of dramatic performance; masquerade, theaters, spoken, drama, dance, theater, dramatize [inaudible], and civic and sacred rituals. The epic of Sundiata and many other epics popular among the Mandinka are reenacted in all these theatrical forms. Griots primarily account Mali's history through dramatized narratives. The written word holds a secondary place in their historiography. Why? Because the world was created through the word and history is transmitted through the creative word, the spoken word, thus, history in the Mandinka language is called Kuma the word or word force. The primacy and preference of an oral dissertation of history in a culture that has two written scripts; they have the Mandinka script and the Arabic script but there is still a preference for using the spoken word. It's predicated on the power of the spoken word which contains and abundance of inyama [assumed spelling]. Inyama means a vital force or a vital energy and this vital force and vital energy is contained in the spoken word at much greater level than it is in the written word. So, it pervades and effectively impacts consciousness more than a written text. That's why they prefer to use the spoken word. So, the inyama force that comes from the spoken word instills in audience the mystical function of language so that they know and understand the history exponentially . . . “

Now, the implications of the African cultures prior to the coming of the Christians as outlined above by professor Nubia Kai reveal the profoundest damage and is the key to understanding the effects caused by Reverend Charles Colcock Jones’ Religious Instruction of the Negroes. What was Reverend Jones’ plan?

“They are an ignorant and wicked people, from the oldest to the youngest. Hence, instruction should be committed to them all, and communicated intelligibly. And that it may be impressed upon their memories, and good order promoted amongst them, it should be communicated frequently and at stated intervals of time.

The plan is this. The Planters form themselves into a voluntary association, and take the religious instruction of the colored population into their own hands. And in this way: - As many of the association as feel themselves called to the work, shall become teachers. An Executive Committee is to regulate the operations of the Society, to establish regular stations, both for instruction during the week and on the Sabbath, and to appoint teachers who shall punctually attend to their respective charges, and communicate instruction altogether orally, and - in as systematic and intelligible a manner as possible, embracing all the principles of the Christian religion as understood by orthodox Protestants, and carefully avoiding all points of doctrine that separate different religious denominations. . . . The only difficulty in the execution of this plan, is the procurement of a sufficient number of efficient teachers. . . . “

Here, we see that Reverend Jones was proposing to use the tradition form of oral instruction used by Afrikan griots. Specifically, Reverend Jones, in 1847, stated,