By Pius Adeleye

Jihadists seize cattle from Fulani herders and funnel the animals into Ghana, part of a large-scale trafficking operation. Pastoralists who resist risk beatings, death or sexual violence.

On a Saturday night in April 2024, during the holy month of Ramadan, dozens of pastoralists gathered for evening prayers at a makeshift cattle camp outside Fada N’Gourma, eastern Burkina Faso’s largest town.

Ali (last name withheld), 17, had arrived late, after driving nearly a hundred cows across open grazing land some eight kilometres away. Dusty and exhausted, he performed the ablution cleansing and slipped into the prayer line.

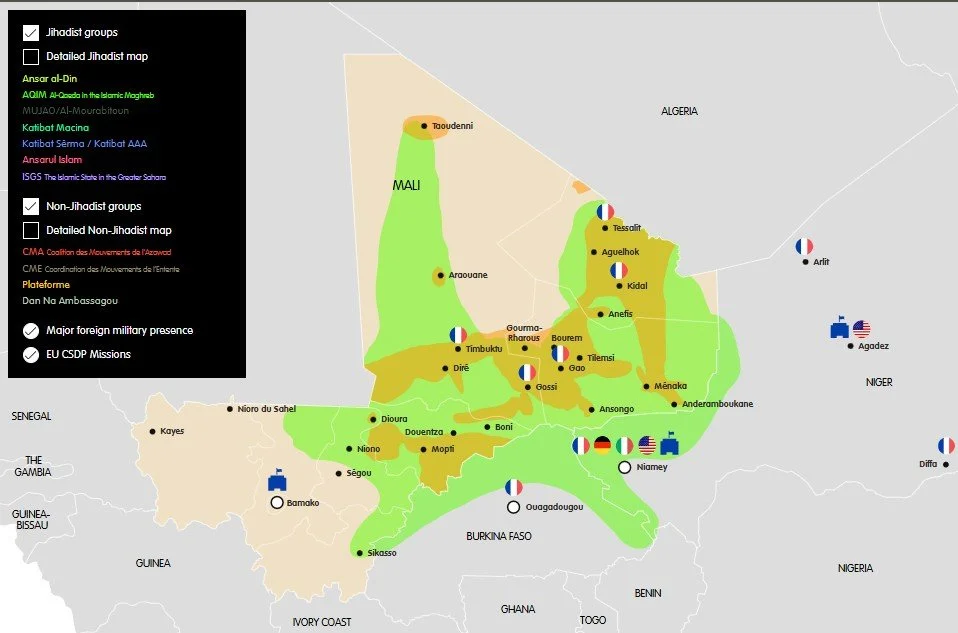

Moments later, the devotion was broken by the grinding wheels of motorcycles. A thick cloud of dust swept over the gathering as armed men stormed the camp. They were fighters from Ansarul Islam, an Al-Qaeda-linked jihadist group under the wider Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) coalition.

Jihadists interrupting prayers to steal cattle

“They did not just come on motorcycles, they came along with two trucks,” says Ali.

For more than seven years, jihadists and bandits in Burkina Faso have raided pastoralist herds, carting cattle away by truck or on foot and selling them cheaply across borders to fund their insurgency. Those who resist risk further looting, beatings and in some cases, death or sexual violence.

“The jihadists accused my father of mixing sorcery with cattle rearing and desecrating the land,” says Ali. “They insisted on taking many of the cows to purify it.” One by one, the animals were driven onto the trucks.

“They took 167 cows and shot my older nephew in the head when he tried to resist,” he says.

For Ali, the raid left the family unsure of the future of a trade they have kept for over two centuries. The herd that once defined their livelihood has been reduced to fewer than 120 cattle.

Livestock for insurgency

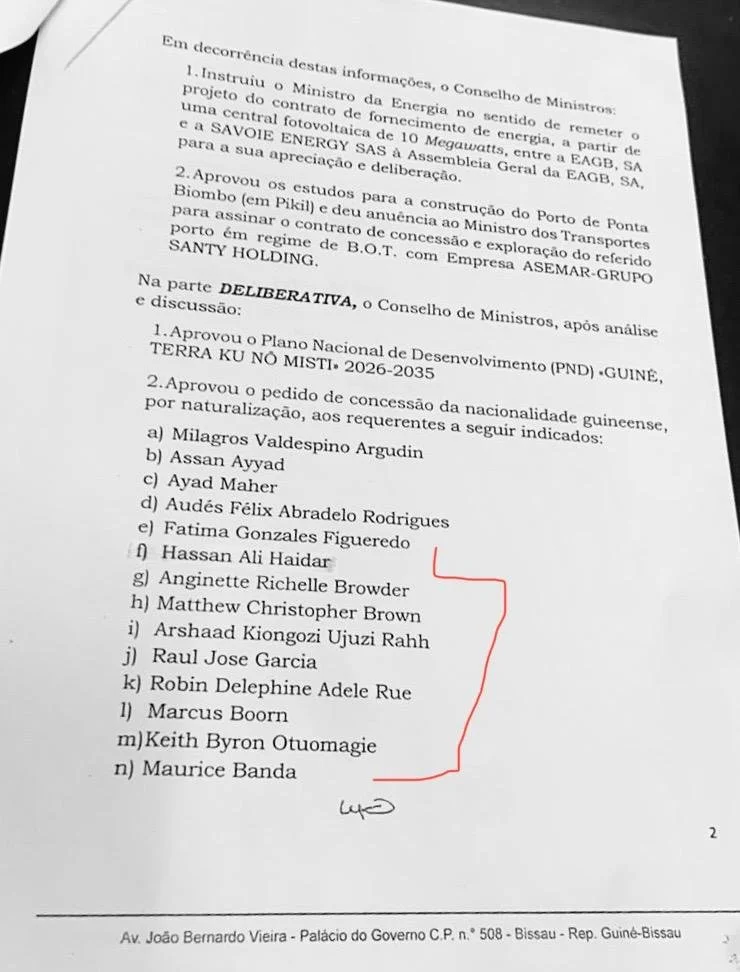

For more than a decade, insurgency has spread across the Sahel, destabilising parts of West Africa. In Burkina Faso, where over 30,000 people have been killed and more than three million displaced, cross-border cattle rustling has become a vital source of financing for armed groups, fuelling the conflict.

Once home to 9.6 million cattle, 15 million goats and 10 million sheep, Burkina Faso has lost some 8 million livestock since 2017, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Most have been stolen by terror groups and militias and sold to traders across borders and in West African coastal markets to bankroll insurgencies.

For many rural Burkinabé families, livestock is a lifeline. Fulani and Tuareg pastoralists, about 10% of the population, play a key role by supplying meat, milk, hides and exports. Yet these communities remain the most exposed to raids and displacement.

In 2023, Mariam Ouedraogo, a 48-year-old widow, watched from a distance as JNIM affiliated militants slit the throat of her 54-year-old husband on their farm near Djibo, a northern town close to the Mali–Niger border. “The jihadists told us to pay taxes on the livestock by demanding about half of the 109 cows,” she says.

“When my husband refused, they killed him and took all our cows,” says Ouedraogo, who fled with her nine-month-old child.

Analysts and eight Burkinabé herders tell The Africa Report that jihadists demand livestock as taxes, or convict animal owners for ridiculous crimes. When herders are isolated with their cattle or when security is weak, raids turn into deadly looting sprees. This is a playbook of many armed groups operating on the continent.

From Mali and the Lake Chad Basin, where JNIM, Islamic State group affiliates and bandits seize herds for revenue, to Somalia and Mozambique, where Al-Shabaab plunders livestock to fund its insurgency, cattle rustling is on the rise.

A butcher speaks

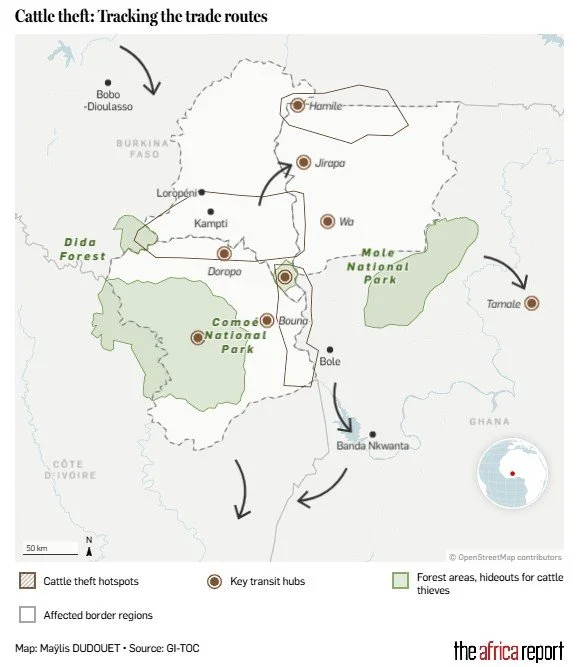

Burkina Faso has sent cattle to its southern West Africa neighbours, particularly the coastal markets, since colonial times. With rising urban demand, weak local supply and long-standing trade with Ouagadougou, Ghana remained one of its biggest markets.

A World Bank data shows Burkina Faso’s 2017 livestock exports to Ghana reached nearly $1.5m, ranking ahead of Côte d’Ivoire, Benin and Togo’s similar trade with Burkina Faso.

Before JNIM’s expansion in 2017, livestock markets in Burkina Faso’s Centre-Sud and South-West bustled with cows penned in rough wooden and rustic metals, as trucks with wooden rails waited for butchers and merchants to strike deals and move the animals to mostly Ghanaian northern towns or southern cities.

But testimonies from analysts, cross-border butchers, dealers and herders in Burkina Faso and Ghana say cattle rustling by jihadists and militias in the Sahel has eclipsed the legal livestock exports to coastal neighbours, with most of the trade now controlled by armed groups and their intermediaries.

“Ivory Coast has been able to hold back the spill of terror from Burkina Faso, but Ghana and Burkina Faso still struggle along their common border,” says 62-year-old Ayamga (last name withheld), a butcher in Bolgatanga, Ghana’s Upper East Region.

For 37 years, Ayamga bought livestock from herders and slaughterhouses in southeast and south-central Burkina Faso for distribution across Ghana. However, since late 2018, he has relied mostly on intermediaries and associates of armed groups who deliver quickly from pickup trucks in border communities.

“Most meat consumed in Ghana, including those moved to the eastern coastal region, comes from bloody raids and stolen livestock,” he says. “This is bloody meat.”

Cows once sold for $650–$800 before jihadists took over the trade. Now he buys them for about $300 and resells at the old price.

Hand-in-hand

What seems like ordinary cattle rustling along the Burkina Faso–Ghana border is part of a chain that exposes deep government weakness, according to cross-border truckers, herders and butchers.

“The trafficking usually happens at night,” says Michael*, a Ghanaian truck driver who since last year has worked with middlemen moving cattle stolen by armed groups.

Before late 2022, those middlemen were mostly Fulani pastoralists aligned with JNIM in Burkina Faso.

But as violence and displacement hit Fulani communities, jihadists turned to non-Fulani butchers and cattle vendors who could slaughter and move livestock. “The armed groups seize the cattle and quickly sell them to the middlemen,” Michael says.

Some cattle are slaughtered and sold to restaurants in Burkina Faso, but many are simply loaded into trucks like his and taken to Ghana.

“Health certificates are forged, and truck drivers are assured that no law enforcement officer will stop us,” he says. “Although I have heard of a few interceptions, I have never been stopped on my route.”

In northern Burkina Faso, JNIM reportedly earned CFA25m-30m ($44,500–$53,400) per month from cattle rustling in 2021, according to a 2023 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. With the recent intensity of rustling, experts say earnings may have increased slightly.

Analysts fear daily cross-border smuggling shows the Burkinabe junta is losing ground in the insurgency and Ghana is emerging as a serious terror risk.

“There are cracks that tell us how clueless both governments are in fighting insecurity,” says a Fada N’Gourma-based security expert, asking not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

“As armed groups expand their presence in Ghana while earning money from smuggling to finance further attacks, West Africa is a ticking [time] bomb,” he says. “It is a matter of time.”

Two fronts

Ali, the teenage herder says a distant relative’s camp in Kaya, Centre-Nord region of Burkina Faso was also plundered earlier this year, not by jihadists, but by the Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie (VDP), a government-backed civilian militia set up to fight jihadist coalition.

A report from conflict monitor group ACLED notes that recruitment for the militia favours sedentary communities, leaving out Fulani and other pastoralists.

Some VDP members have been accused of stealing livestock for personal gain and targeting Fulani communities suspected of supporting jihadists, carrying out attacks and seizing their animals.

“They are stealing our lives and our animals,” says Ali, referring to both jihadists and the VDP. “That is all we have, but we cannot protect them. It is a difficult fight to defend.”

*Names have been changed to protect their identity