“In fact in the tragic history of revolutionary Africa, so many of whose leaders have left only a faint memory, three great figures stand out indisputably: Kwame Nkrumah, the visionary; Patrice Lumumba, the martyr; Amilcar Cabral, the unifier. As a unifier and mobilizer, he was both a theoretician and a man of action indefatigably in pursuit of reality, by revealing the deep roots, fundamental causes, so often blurred in the tumult of revolutionary action. For Guineans and Cape Verddians, he is the founder of the nation and the guide . . . .”

- Mario de Andrade, Biographical notes, Unity and Struggle: Speeches and Writings of Amilcar Cabral

“These long and difficult campaign for anti-colonial and post-colonial liberation and development in the African empire of the Portuguese - in Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome - produced a number of outstanding revolutionary thinkers who proved able to live their thought in their practice, and who, in doing that, have displayed a rare and often decisive talent for explanation in writing and the spoken word. Among these thinkers, and even at the head of them, was Amilcar Cabral, the author of the writing in this book. Murdered by the agents of Portuguese Fascism in 1973, his work lives after him and is there for inspection. A supreme educator in the widest sense of the word, Cabral can be recognized even now as being among the great figures of our time. We need not wait for history’s judgement to tell us that.. . . . Suffice it to say that he was loved as well as followed, and he was both because he was large hearted, entirely committed, devoted to his people’s progress. . . . He raised an army, led and taught it how to fight, gave it detailed orders, supervised its every major action; but he did all this, by the habit of his practice, through a process of collective political discussion. . . . Cabral gave his life for the liberation that he served, and he had to give it long before his time and when he was still in the full zest and vigour of his work..”

- Basil Davidson, Introduction, Unity and Struggle: Speeches and Writings of Amilcar Cabral

AMILCAR CABRAL DESCRIBES BINHAM B’URASSA (BALANTA PEOPLE)

Excerpt from Part 1 The Weapon of Theory, Party Principles and Political Practice

“The Balanta have what is called a horizontal society, meaning that they do not have classes one above the other. The Balanta do not have great chiefs; it was the Portuguese who made chiefs for them. Each family, each compound is autonomous and if there is any difficulty, it is a council of elders which settles it. There is no State, no authority which rules everybody. If there has been in our times, you are young; it was imposed by the Portuguese. There are Mandinga imposed as chiefs of the Balanta, or former African policemen turned into chiefs. The Balanta cannot resist, and they accept, but they are only play-acting towards the chief. Each one rules in his own house and there is understanding among them. They join together to work in the fields, etc.. and there is not much talk. And it can even happen in the Balanta group that there are two family compounds close to each other and they do not get on with each other because of a land dispute or some other quarrel from the past. They do not want anything to do with each other. But these are ancient customs whose origin one would need to explain, if we had time. Old stories, of blood, of marriage, of beliefs, etc. Balanta society is like this: the more land you work, the richer you are, but the wealth is not to be hoarded, it is to be spent, for one individual cannot be much more than another. That is the principle of Balanta society, as of other societies in our land. Whereas the Fula and Manjaco have chiefs, but they were not imposed by the Portuguese; it is part of the evolution of their history. Obviously we must tell you that in Guine the Fula and Mandinga at least are folk who came from abroad. The majority of Fula and Mandinga in our land were original inhabitants who became Fula and Mandinga. It is good to know this well so as to understand certain aspects. Because if we compare the life style of Fula in our land with that of the true Fula in other regions of Africa, there is a slight difference; even in the Futa-Djalon there is a difference. In our land many became Fula; former Mandinga became Fula. Even the Mandigna, who came and conquered as far as the Mansoa region ‘Mandingized’ persons and changed them into Mandinga. The Balanta refused and many people say that the very word ‘balanta’ means those who refuse. The Balanta is someone who is not convinced, who denies. But they did not refuse so much, because we find the Balanta-Mane, the Mansoaner. There were always some who accepted, and who were gradually growing in number, as they accepted becoming Moslems.

Balanta, Pepel, Mancanha, etc., were all folk from the interior of Africa whom the Mandinga drove towards the sea. The Sussu of the Republic of Guinea, for example, come from Futa-Djalon, from where the Mandinga and the Fula drove them, The Mandinga drove them and later came the Fula who in turn drove the Mandinga. As we have said, the Fula society, for example, or the Manjaco society are societies which have classes from the bottom to the top. With the Balanta it is not like that: anyone who holds his head very high is not respected any more, already wants to become a white man, etc. For example, if someone has grown a great deal of rice, he must hold a great feast, to use it up. Whereas the Fula and Manjaco have other rules, with some higher then others. This means that the Manjaco and Fula have what are called vertical societies. At the top there is the chief, then follow the religious leaders, the important religious figures, who with the chiefs form a class. Then come others of various professions (cobblers, blacksmiths, goldsmiths) who, in any society, do not have equal rights with those at the top. By tradition, anyone who was a goldsmith was even ashamed of it - all the more if he were a ‘griot’ (minstrel). So we have a series of professions in a hierarchy, in a ladder, one below the other. The blacksmith is not the same as the cobbler, the cobbler is not the same as the goldsmith, etc.; each one has his distinct profession. Then come the great mass of folk who till the ground. They till to eat and live, they till the ground for the chiegs, according to custom. This is Fula and Manjaco society, with all the theories this implies such as that a given chief is linked to God. Among the Manjaco, for example, if someone is a tiller, he cannot till the ground without the chief’s order, for the chief carries the word of God to him. Everyone is free to believe what he wishes. But why is the whole cycle created? So that those who are on top can maintain the certainty that those who are below will not rise up against them. But in our land it has sometimes occurred, among the Fula, for example, that those who were below rose up and struggled against those at the top. There have sometimes been major peasants’ revolts. We have, for example, the case of Mussa Molo who overthrew the king and took his place. But as soon as he had taken the place, he adopted the same ancient law, because that was what suited him. Everything remained the same, because like that he was well off. And he soon forgot his origin. That, unhappily, is what many folk want.

In this bush society, a great number of Balanta adhered to the struggle, and this is not by accident, nor is it because Balanta are better than others. It is because of their type of society, a horizontal (level) society, but of free men, who want to be free, who do not have oppression at the top, except the oppression of the Portuguese. The Balanta is his own man and the Portuguese is over him, because he knows that the chief there, Mamadu, is in no way his chief, but is a creature of the Portuguese. So he is the more interested in putting an end to this so as to remain totally free. And that is also why, when some Party element makes a mistake with the Balanta, they do not like it and become angered quickly, more quickly than any other group.

Among the Fula and Manjaco it is not like this. The broad mass who suffer in fact are at the bottom, tillers of the soil (peasants). But there are many folk between them and the Portuguese. They are used to suffering, to suffering at the hands of their own folk, from the behaviour of their own folk. Someone who tills the soil has to work for all the chiefs, who are numerous, and for the district officers. So we have found the following: once they had really understood, a large proportion of the peasants adhered to the struggle, except one or other group with whom we had not worked well. . . .

In the societies with a horizontal structure, like the Balanta society, for example,the distribution of cultural levels is more or less uniform, variations being linked solely to individual characteristics and to age groups. In the societies with a vertical structure, like that of the Fula for example, there are important variations from the top to the bottom of the social pyramid. This shows once more the close connexion between the cultural factor and the economic factor, and also explains the difference in the overall or sectoral behavior of these two ethnic groups towards the liberation movement.“

Excerpt from Agricultural Census of Guine (1953)

“The Balanta tribe (30.07%), Fula (28.61%), Mandinga (15.69%) and Manjaco (12.62%) have the largest share of cultivated area, making up 86.99% of the overall total. . . . In other words: there are in Guine about twenty-five different tribes (1950 Population Census), of whom only a quarter have almost the whole of the cultivated area, with four peoples particularly prominent (Balanta, Fula, Mandinga and Manjaco). . . .

The largest cultivated areas correspond generally to the largest multiple cropped areas. The Fula people who have the largest area under crops do not, however, cultivate the largest true area (the Balanta people do this), as the former practise intenesive multiple-cropping (31, 811 hectares). . . .

Taking into consideration only the main crops (rice, cereals and groundnuts), it is seen that the Balanta people provide about half the area for floodplain rice (47.16%) the Manjaco people (14.30 %), Fula (12.27%) and Mandinga (10.53%) follow. . . .

The Balanta people supply 61.01% of the total production of floodplain rice. They are followed by the Manjaco people (12.06%), Fula (7.06%), Mandinga (6.9%) and Pepel (5.01%). . . . The highest average yields are those attained by the Balanta people, Pepel and Manjaco.

The Fula people supply nearly half the groundnuts production (43.61%), followed by the Mandinga people (22.71%), Balanta (17.92%), Manjaco (7.58%), Mancanha (3.80%) and Balanta-Mane (1.24%). . . .

For floodplain rice the highest averages (1800 kilograms) are found in the catio region and are attained by the Balanta people. . . .

In relation to trees bearing fruit, the Mandinga people (27.40%), Fula (20.74%), Balanta (16.88%) and Manjaco (12.11%) show the highest number of bushes. . . .

The Balanta people have the highest number of mangoes (fruit bearing, 33.26%; not bearing, 37.65%) . . . .

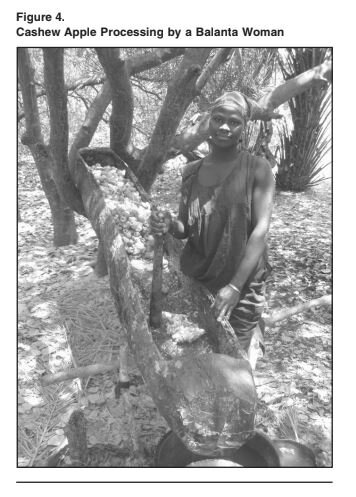

The Balanta and Mancanha peoples have the highest number of cashews.”

Some of the videos below are in Portuguese. Click “CC” and change the settings to “Auto-translate - English” to get English Subtitles. Click here for more on Amilcar Cabral and the Revolutionary War.

-

December 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 ARCHIVE Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 SANKOFA - HOW RAS NATHANIEL FIRST RETURNED TO AFRICA AND HOW HE EMERGED AS SIPHIWE BALEKA Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 17, 2025 SANKOFA - REMEMBERING THE AFRICAN UNION GRAND DEBATE ON THE UNITED STATES OF AFRICA : SIPHIWE BALEKA'S REPORTS FROM ACCRA, GHANA IN 2007 TO THE BIRTH OF THE PAN AFRICAN FEDERALIST MOVEMENT IN 2015 Dec 17, 2025

- November 2025

-

October 2025

- Oct 12, 2025 Siphiwe Baleka and Sânebickté Juliana Yala Nhanca Official Wedding Album Oct 12, 2025

-

September 2025

- Sep 17, 2025 A BALANTA RASTAFARITE BIBLE STUDY: FROM ISRAEL, JUDAH, DAVID, SOLOMON AND SHEBA TO MENELIK AND RAS TAFARI - HAILE SELASSIE I KING OF KINGS, LORD OF LORDS, CONQUERING LION OF JUDAH AND ELECT OF GOD Sep 17, 2025

- Sep 16, 2025 A BALANTA RASTAFARITE BIBLE STUDY: IN THE BEGINNING, FROM A BLACK CUSHITIC ETHIOPIAN ADAM AND NOAH TO A MIXED SEMITIC WHITE ABRA-HAM AND MOSES Sep 16, 2025

-

May 2025

- May 23, 2025 Omowale Malcolm X and the Republic of New Afrika May 23, 2025

- May 5, 2025 HISTORY OF THE MODERN REPARATIONS MOVEMENT THAT STARTED IN THE UNITED STATES AND HAS SPREAD THROUGHOUT THE AFRICAN WORLD May 5, 2025

-

April 2025

- Apr 1, 2025 The Military Order of Jesus Christ in Portugal Started the Misnamed TransAtlantic Slave Trade Apr 1, 2025

-

March 2025

- Mar 24, 2025 THE PAN AFRICAN, REPATRIATION, BACK-TO-AFRICA HISTORY THAT YOU WERE NOT TOLD Mar 24, 2025

- Mar 21, 2025 Malcom X Speaks on Reparations Mar 21, 2025

- January 2025

-

October 2024

- Oct 22, 2024 THE TRUE STORY OF THE 9TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS - ALL THE BACKGROUND Oct 22, 2024

-

September 2024

- Sep 7, 2024 Dr. John Henrik Clarke - African Americans the lonely nation away from home Sep 7, 2024

-

August 2024

- Aug 31, 2024 AN ANSWER TO THOSE WHO SHIFT THE BLAME TO AFRICANS FOR SELLING THEIR OWN PEOPLE INTO CHATTEL SLAVERY IN THE AMERICAS Aug 31, 2024

- Aug 18, 2024 IMARI OBADELE ON MALCOLM X AND REPARATIONS Aug 18, 2024

- Aug 17, 2024 𝐏𝐆𝐑𝐍𝐀 𝐅𝐨𝐫𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐧 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫𝐬 𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲 - Queen Mother Audley Moore's Speech to the Summit Meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Kampala, Uganda - July 28, 1975 Aug 17, 2024

- Aug 15, 2024 THE ABSENCE OF THE BLACK NATIONALISTS IN TODAY’S REPARATIONS MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES: A FAILURE TO LEARN THE LESSONS OF HISTORY Aug 15, 2024

- Aug 13, 2024 CULTURAL CARRYOVERS, EPIGENETICS AND CONNECTING THE DOTS: BALANTA, PALMERES AND THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRIKA - A TRADITION OF LIBERATION, INDEPENDENCE AND REPARATIONS Aug 13, 2024

-

June 2024

- Jun 28, 2024 THE UNITED STATES AND ITS COLONIAL EMPIRE Jun 28, 2024

- June 2023

-

March 2023

- Mar 14, 2023 Outcome of the 4th Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1: Pan African TV and Radio Mar 14, 2023

- Mar 14, 2023 Council of Pan African Diaspora Elders Letter of Support to President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa of The Republic of Zimbabwe for the 8PAC1 Mar 14, 2023

- Mar 9, 2023 Outcome of the 3rd Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1: Diaspora Pan African Capital Fund Mar 9, 2023

- Mar 3, 2023 TOWARDS THE 8TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS PART 1: LESSONS FROM THE 6TH PAC AND 7TH PAC Mar 3, 2023

- Mar 2, 2023 Divide and Conquer Diplomacy of Lisbon and Washington 1973: Coopting the PAIGC and the Balanta People Mar 2, 2023

-

February 2023

- Feb 28, 2023 The African Union and the African Diaspora - Tracking the AU 6th Region Initiative and the Right to Return Citizenship: A Resource for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1 in Harare, Zimbabwe Feb 28, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PREPARING FOR THE AFRO DESCENDANT/NEW AFRIKAN PLEBISCITE FOR SELF DETERMINATION IN THE UNITED STATES: UNDERSTANDING THE BERLIN CONFERENCE OF 1884 Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PREPARING FOR THE AFRO DESCENDANT/NEW AFRIKAN PLEBISCITE FOR SELF DETERMINATION IN THE UNITED STATES: UNDERSTANDING DECOLONIZATION Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PLEBISCITES IN WORLD HISTORY Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 African Liberation and the Use of Plebiscites Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 25, 2023 OUTCOME OF SECOND PREPARATORY MEETING FOR THE 8TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS PART 1 IN HARARE, ZIMBABWE Feb 25, 2023

- Feb 20, 2023 Outcome of the First Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1 in Harare, Zimbabwe Feb 20, 2023

- Feb 19, 2023 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MODERN RIGHT TO RETURN CITIZENSHIP MOVEMENT SINCE THE BERLIN CONFERENCE 1884: A PRESENTATION TO THE 8TH PAC PART 1 PREPARATORY MEETING DISCUSSING PATHWAYS TO CITIZENSHIP Feb 19, 2023

- Feb 14, 2023 Defining the Afro Descendants' Right to Return (RTR) to their Ancestral Homelands on the African Continent for the 8PAC Part 1 Feb 14, 2023

-

December 2022

- Dec 25, 2022 The African American Case for Independence at the International Court of Justice Dec 25, 2022

-

November 2022

- Nov 3, 2022 Secrets of the Forest People: Learning the Bantu Culture in Cameroon Nov 3, 2022

-

October 2022

- Oct 19, 2022 Celebrating the 50 Year Anniversary of Amilcar Cabral's Meeting With African Americans, October 20, 1972 Oct 19, 2022

-

September 2022

- Sep 7, 2022 THE POTENTIAL OF A MINORITY REVOLUTION IN THE USA - The Crusader, August 1965 Sep 7, 2022

- Sep 7, 2022 THE AFRICAN LIBERATION READER Sep 7, 2022

- August 2022

-

July 2022

- Jul 20, 2022 DESCENDENTES DE BALANTA LIDERAM MOVIMENTO DE REPARAÇÃO NO VATICANO: RESPONSABILIZAM OS REPRESENTANTES DE JESUS CRISTO PELA ESCRAVAÇÃO DOS POVOS AFRICANO Jul 20, 2022

- Jul 20, 2022 BALANTA DESCENDANTS LEAD REPARATIONS MOVEMENT AT THE VATICAN: HOLD THE REPRESENTATIVES OF JESUS CHRIST RESPONSIBLE FOR THE ENSLAVEMENT OF AFRICAN PEOPLE Jul 20, 2022

- June 2022

- January 2022

-

September 2021

- Sep 23, 2021 Lessons From Amilcar Cabral and Siphiwe Baleka: The Dum Diversas War and the Incomplete Independence of Guinea Bissau Sep 23, 2021

- Sep 2, 2021 BRIEF NOTES ON BALANTA HISTORY BEFORE AND AFTER GUINEA BISSAU INDEPENDENCE Sep 2, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 25, 2021 BRIEF NOTES ON BALANTA MIGRATION IN GUINEA BISSAU Aug 25, 2021

- Aug 19, 2021 Jornada de Quintino Medi para descobrir a Mãe Fula de Amílcar Cabral na Guiné-Bissau Aug 19, 2021

- Aug 19, 2021 Quintino Medi's Journey to Discover Amilcar Cabral's Fula Mother in Guinea Bissau Aug 19, 2021

- Aug 8, 2021 Space and Time in the African Worldview: Excerpt from Remembering the Dismembered Continent by Ayi Kwei Armah Aug 8, 2021

-

May 2021

- May 30, 2021 Historic Moment in Guinea Bissau: Denita Madyun-Baskerville is the First Balanta Woman to Return to Her Ancestral Homeland Since the Slave Trade May 30, 2021

- May 27, 2021 Sketches of the History of Balanta People in America: Anthology Series 1 now available! May 27, 2021

- May 5, 2021 MAY 5TH - THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY AND EVIDENCE THAT THE ANCESTORS OF AFRICAN PEOPLE COMMUNICATE TO THEIR DESCENDANTS ON EARTH AND SHAPE WORLD EVENTS May 5, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 6, 2021 CLARIFYING THE POLITICAL AND LEGAL STATUS OF 1,108 GENERATIONS OF MY FAMILY Apr 6, 2021

-

March 2021

- Mar 23, 2021 Balanta Marriage Customs: KWÂSSI, B-BÂSTI and MHÂH M-NANHI Mar 23, 2021

- February 2021

-

November 2020

- Nov 24, 2020 Oligarchy: The Spiritual and International Legal Wars Against the Balanta Nov 24, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 25, 2020 The Civil, Political and Legal Illiteracy of African Americans: Failure to Apply the Framework of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Oct 25, 2020

- Oct 11, 2020 Notes on Hugo Grotius' Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty (1604) Oct 11, 2020

- Oct 10, 2020 The Spiritual Protective Function of the Balanta Placenta Tradition, The United States Birth Certificate and the Spiritual Damage of Slavery Oct 10, 2020

- Oct 6, 2020 B’KINDEU & RANSOM: BALANTA PEOPLE REFUSED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE CRIMINAL EUROPEAN TRANS ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE Oct 6, 2020

- Oct 1, 2020 From Nhacra to North Carolina: The Story of Brassa Nchabra and The Blake Family, 1760 to 1890 Oct 1, 2020

-

September 2020

- Sep 7, 2020 BALANTA AND THE POISON ORDEAL Sep 7, 2020

- August 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 4, 2020 KNOW YOUR AMERICAN HISTORY: A BALANTA FAMILY ON JULY 4 1776 Jul 4, 2020

- Jul 3, 2020 LAND HAS ALWAYS BEEN CENTRAL TO THE SOLUTION OF AMERICA'S RACE PROBLEM Jul 3, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 24, 2020 The Black Liberation Movement (BLM), Balanta, Rastafari, and America's Drug War: Chicago Police Attacks on January 27, 1997 and August 6, 1999 Jun 24, 2020

- Jun 22, 2020 Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) Reader Jun 22, 2020

- Jun 21, 2020 A BALANTA PANTHER: STEPHEN HOBBS AND THE CHICAGO BLACK PANTHER PARTY Jun 21, 2020

- Jun 9, 2020 REVISITING THE BATTLE PLAN: THE STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRIKA TO LIBERATE BLACK AMERICANS Jun 9, 2020

- Jun 8, 2020 JUNE 8, 1954: THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY IN 20TH CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Jun 8, 2020

- Jun 2, 2020 Marcus Garvey Message to the People: Lesson 16 Propaganda (and War), The Course of African Philosophy Jun 2, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 17, 2020 THE BALANTA STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE AND EQUALITY: BRIEF SKETCHES OF ONE STRONG FAMILY'S ROLE IN AMERICAN HISTORY May 17, 2020

- May 9, 2020 KNOW YOURSELF, KNOW YOUR ENEMY: UNDERSTANDING EUROPEAN HISTORY PRIOR TO THEIR ARRIVAL IN WEST AFRICA May 9, 2020

- May 9, 2020 THE BOOK AFRICAN AMERICANS SHOULD BE READING: NOTES ON THE ORIGINS OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN INTERESTS IN INTERNATIONAL LAW May 9, 2020

- May 8, 2020 The B'rassa Fight Against the Befera: Learning from the Revolutionaries from India May 8, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 10, 2020 Black Bodies of Knowledge: Information Gangsters, Guerrillas and Notes on an Effective History by John Fiske Apr 10, 2020

- Apr 2, 2020 CREDO MUTWA ON THE RACE THAT DIED: A TALE OF TECHNOLOGY AND A WARNING TO THE FUTURE Apr 2, 2020

- March 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 19, 2020 MISSING MIDDLE PASSAGE DOCUMENTS: THE CONSEQUENCE FOR BALANTA, MENDE, TEMNE AND OTHER SENEGAMBIAN PEOPLES BROUGHT TO THE UNITED STATES Feb 19, 2020

- Feb 3, 2020 THE MALI KINGDOM AND MANSA MUSA WERE IMPERIALIST SLAVE TRADERS: REVISITING AFRICAN HISTORY FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE OPPRESSED Feb 3, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 29, 2019 AFRICAN HISTORIANS SPEAK ON BLACK-WHITE RELATIONSHIPS AND THEIR MIXED RACE OFFSPRING Dec 29, 2019

- Dec 3, 2019 Homosexuality Contemplated From African Spirituality Dec 3, 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Befera: The White Christian Witches of the Balanta Worldview Dec 1, 2019

-

November 2019

- Nov 16, 2019 Balanta and the Banking System: A Case Study of the Criminal Application of Fictitious Corporate Statutory Law Nov 16, 2019

- Nov 6, 2019 SUMMARY OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE Nov 6, 2019

- Nov 6, 2019 DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE Nov 6, 2019

- Nov 4, 2019 Timeline of American History And The Birth of White Supremacy and White Privilege in America Nov 4, 2019

-

October 2019

- Oct 29, 2019 LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH THE ENGLISH Oct 29, 2019

- Oct 29, 2019 LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH EUROPEAN CHRISTIANS Oct 29, 2019

- Oct 28, 2019 DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES DURING THE BALANTA MIGRATION PERIOD Oct 28, 2019

- Oct 28, 2019 ORIGIN OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES Oct 28, 2019

- Oct 25, 2019 HOW THE AFRICAN UNION WAS ESTABLISHED TO INCLUDE THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Oct 25, 2019

- Oct 22, 2019 THE BALANTA FOUNDER OF THE AFRICAN UNION 6TH REGION CAMPAIGN Oct 22, 2019

- Oct 18, 2019 Amilcar Cabral Describes Balanta People Oct 18, 2019

- Oct 16, 2019 AN ANSWER TO THOSE WHO CLAIM THAT AFRICAN AMERICANS ARE HEBREW OR “LOST JEWS” Oct 16, 2019

- Oct 9, 2019 26 Principles of the Great Belief of the Balanta Ancient Ancestors Oct 9, 2019

-

September 2019

- Sep 19, 2019 Reviewing the Sudanic/TaNihisi Origins of the Balanta Sep 19, 2019